Regarding Tip #1 - keeping spare lug nuts is a good idea, but dropping them on black asphalt or in low light situations is one reason the lugs nuts in Tip 2 are painted bright yellow :-)

[Editor’s note: Even though this article originally appeared back in 2013, it still holds water today.]

Story and Photography by Alan Cesar

Your car is built to the inch of every rule, designed to gain tenths of a second per lap over everyone else. Your last pit stop, however, went 14 seconds over your 5-minute minimum because you couldn’t find that lug nut you dropped. Struggling and fumbling are the last things you need when time is tight and championship bragging rights—or boxes of nickels—are on the line.

In Grand-Am racing, pit stops happen in mere seconds. There’s a lot of planning, practice and experience crammed into those few moments you see over and over on TV. At this year’s Rolex 24 At Daytona, we were again embedded with Team Sahlen for their first hot dog-fueled attempt in the Daytona Prototype class, and we got to see these stops—as well as how they prepare for each one—up close.

Though the Riley/BMW prototype is new and high-tech, much of Team Sahlen’s crew is the same as last year’s. There are few changes to the process compared to running a GT car: There are four wheel nuts total instead of 20 lug nuts, but there are still four tires, one driver, and two fuel fill hoses.

A professional team’s precision and rigor can easily help any club racer who wants shorter stops—even in the crapcan pits. Speedy stops call for the same degree of dedication as fast lap times. The list of requirements is short on special equipment but long on process improvements and, most of all, practice.

None of it is super-secret magic sauce, though a few special tools do help. Race teams invest in a pit socket and lug nuts that will fit inside it. Pit sockets are balanced so they don’t wobble when spun freely; they’re designed to go on and off a lug nut easily while the socket is still spinning; and there’s a spring inside to spit out the lug nut as soon as you back off the wheel stud.

One of these sockets costs around $50 at any speed shop, but they’re only made for 1-inch lug nuts. If you can’t fit 1-inch lug nuts inside your wheel centers, you’ll have to change wheels the harder way.

You may not be allowed to use—or be able to afford—the gravity-fed two-hose fuel system used in Grand-Am. However, a 5-gallon fuel jug by VP Racing is only $25 from pretty much any speed shop, and it’s much better than that canister you use to gas your lawn mower.

Your car also probably won’t have a pneumatic on-board jack system. But fast-lifting aluminum floor jacks are available for less than $100 from Harbor Freight, and they’re nice to have in the garage anyway.

Beyond those bits, the only tools you’ll need are arms, legs, brains and muscle memory. Everyone can bring home good ideas by taking a close look at how a professional team does it. Here are some important points we noticed while crewing for Team Sahlen.

Lug nuts get dropped. Keep extras in your pockets so you’re not searching black asphalt for a black lug nut or reaching under a car for the one that’s directly under the red-hot exhaust. When dealing with big, center lock nuts, all the members of the Team Sahlen tire crew keep one hung on the front of their belts.

Team Sahlen’s DP car uses center-lock lug nuts, but the Mazda RX-8 they used to run had five lug nuts on each wheel. With that setup, they used 3M weatherstrip adhesive to glue a fresh set of lug nuts in the lug seats of each wheel. Gluing them in place meant the pit crew could just jam the wheel onto the hub and the lugs would be hanging on the bull-nosed studs, ready to be zipped on with the air gun.

They also lubed the lug studs with a mix of Marvel Mystery Oil and anti-seize. Slippery threads helped keep off the glue, and made the installation just a bit smoother.

Electric impact wrenches can be pricey, especially cordless ones. The right-size air tank will operate a pneumatic impact gun long enough for a tire change, and a small compressor can repressurize it between pit stops. Grand-Am teams just obtain prefilled nitrogen tanks from Airgas.

Don’t waste time checking your tire pressures when the car is in front of you. Set them before the race, and check them before your driver is entering the pit or paddock.

Will you know off the top of your head all the sockets and wrenches needed to replace a bent strut? Will you know immediately if that’s the right or left brake caliper? If you have spare parts, organize them and mark the tools you need to change them. If you have enough tools, you can simply pair them up with their corresponding parts.

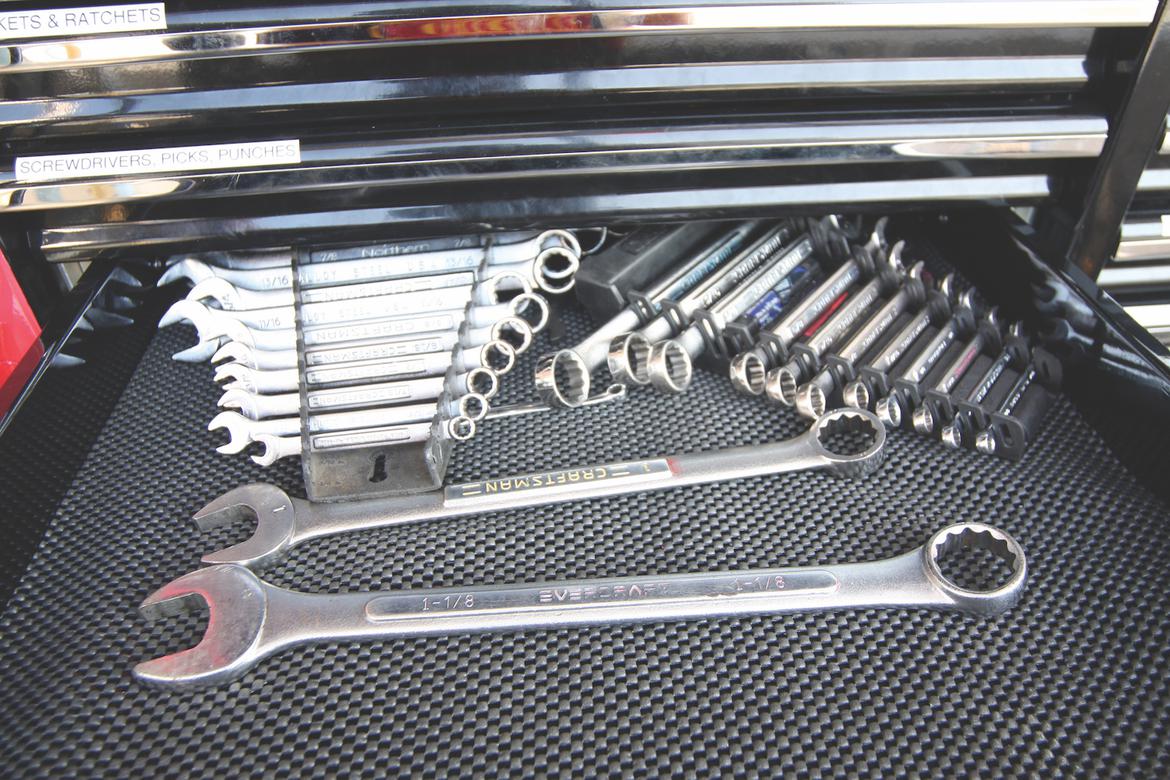

Don’t hunt for that elusive 13mm wrench. Organize your tools, and reorganize them after each stop. This is Team Sahlen’s toolbox after 20 hours of racing.

Each crewmember should have a specific job with carefully detailed procedures. The outside tire changer, for example, goes to the right of the fire extinguisher guy, who plants his feet to keep the air hose from getting dragged under the car.

Anyone going over the pit wall should also be hyper-aware of the penalties regarding pit procedure. Are you allowed to step over before the car has completely stopped? How many people are allowed over the wall? Is everyone wearing the necessary gear? Read the rules and share them with your team.

All parties should practice their roles—a lot. Team Sahlen even has a pit wall in their shop so their crew can practice hopping over it. In your own driveway, mock up your pit spot and have your drivers and crew bring their gear. Spend an afternoon fueling the car, changing tires and changing drivers.

Know your job and the order in which things should happen—is it belts first or the CoolShirt or the radio? Make any tweaks necessary to keep the process moving along smoothly.

Communicate. A pit board and a spotter may be enough if the track is laid out to allow fast communication between the spotter and the pit crew. Two-way radio communication with the driver and all the crew, however, can help everyone prepare for unscheduled stops.

Nonverbal communication is important, too. A “lollipop”—the car number on a long pole sticking out into pit road—helps prevent the driver from blowing by your spot. Make only one person responsible for signaling, “Go!” to the driver. That person should receive distinct signals from every other crewmember indicating that the job is done and they’re clear of the car. People don’t want cars dropped on their toes.

Finally, remember that you’re a team. No one person can win a race, but one person can sometimes lose it. Everyone depends on you, and you depend on everyone else. Working together toward a common goal, your team will establish a bond that will last long after the race is over—even if you finish dead last.

Displaying 1-1 of 1 commentsView all comments on the GRM forums

You'll need to log in to post.