Whether or not you’re a fan of his music, you have to recognize Trent Reznor—the creative force behind Nine Inch Nails—as a bit of a pioneer in the music industry. Sure, he took inspiration from the many bands who paved the way before him, but he did something particularly creative when he released “Year Zero” in 2007: He made several of the album’s songs available via Apple’s GarageBand software. Listeners could then take an active approach to the music, remixing, tweaking and rearranging tracks within the software and creating something wholly their own from the pieces Reznor gave them.

Bear with us; we’re getting there.

See, plenty of factories have done racing directly. They’ve fielded pure factory teams and had great success, but their efforts have always felt somewhat disconnected from us and our daily lives—like they’re on the other side of the pit wall from the rest of the world.

Some car companies, however, have taken the Reznor approach. (Well, actually, if you look at the timing, he took their approach, but we’re trying to roll with a metaphor here, so cut us some slack.) Anyway, some factories have preferred to give privateers the keys to the kingdom and let them run with that freedom.. While these manufacturers might have maintained in-house teams for R&D, much of the flavor of their racing efforts has come from privateer efforts.

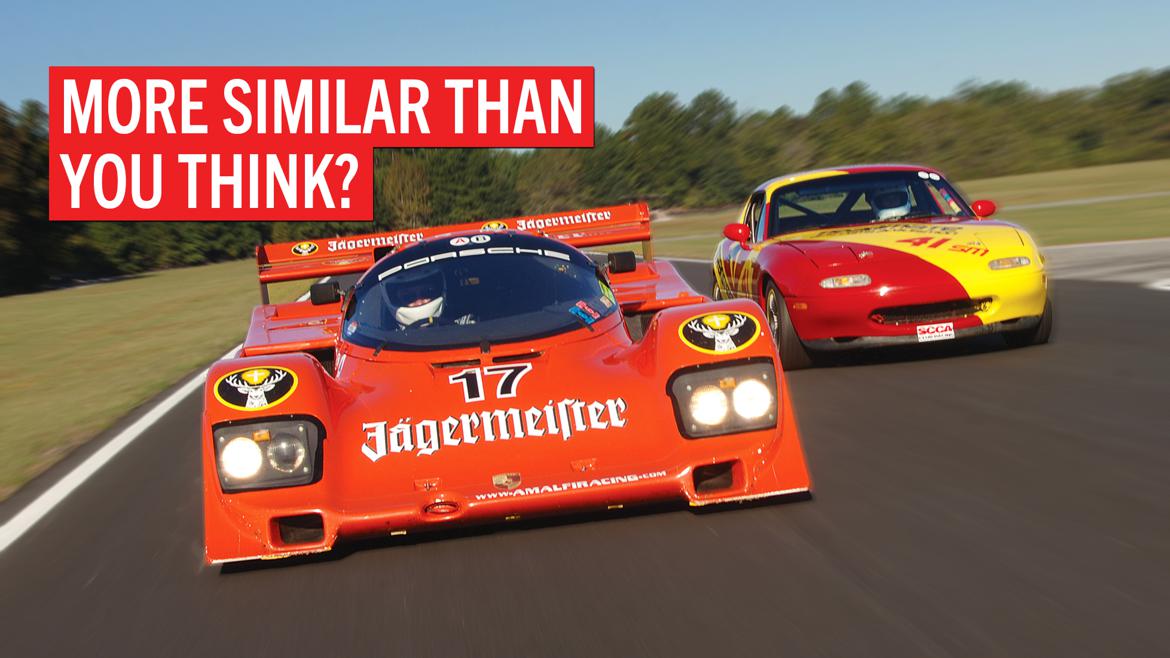

And that’s where the 962 and the Spec Miata come in.

Birds of a Feather

While they couldn’t be further apart in specifications and scope, the 962 and Spec Miata are tantalizingly similar in philosophy. Both cars can be purchased by any racer or team—with the proper funding, of course—and campaigned with the factory’s blessing and support.

Spec Miata is one of the most popular one-make series of all time. Both SCCA and NASA have accepted the class, and field sizes have forced race organizers to enact and enforce registration limits at some events.

The 962 knows a thing or two about popularity, too. The overwhelming number of these cars nearly turned the IMSA GTP series into a de facto spec class in the late 1980s. For a few years there, GTP basically featured a slew of customer-entered 962s against a sprinkling of factory-run cars from other manufacturers.

Prototype Porsche

The 962 was the immediate offspring of the 956, Porsche’s Group C monster that appeared in Europe in 1982 and went on to win five straight FIA World Sportscar Championship titles. While the car was similar in design and construction to the monocoque 956, the 962’s front wheels were pushed forward to place the driver’s feet behind the wheel centerline to meet contemporary IMSA regulations. And instead of the 956’s water-cooled powerplant, the 962 was fitted with an evolution of the air-cooled flat-six that had powered numerous IMSA-winning Porsche 935s.

From the beginning, the 962 was perceived as a “customer” car. In fact, the only drivers to ever campaign a “factory” 962 in the States were Mario and Michael Andretti at the 1984 running of the Rolex 24 At Daytona. Customers began taking delivery of the cars shortly after that, but success was not instant; the 962 had trouble keeping up with the Jags and Marches that had been dominating the series.

Access to the flat-six is not bad once the rear bodywork is tilted away, though the 962’s guts look more like the innards of a fighter jet than the race cars we’re used to seeing.

The first glimpse of the 962’s impending domination would come courtesy of Al Holbert, after his team replaced the as-delivered 2.8-liter engine with a 3.2-liter unit. The 962 would then go on to win four straight IMSA championships—1985 through 1988—as well as five of the next seven Daytona 24-hour contests.

After that, the factory technology wars began to take over, and the 962s were soon overshadowed by the whiz-bang Chevy, Nissan and Toyota GTP efforts. None of these cars were built in mass quantities, as they were limited to factory-run efforts.

Still, the 962 remained competitive right to the end, even scoring a victory in the final year of GTP at Road America. Manuel Reuter and the driver known as John Winter gave the 962 its final IMSA win in that 1993 season.

After the GTP glory days faded, the 962’s professional last hurrah was an overall win at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1994. The winning car was actually a modified street car built by Dauer Racing from a 962 tub—so it was basically a race car that was turned into a street car, then back into a race car. After all that, it still won.

Mischievous Mazda

Spec Miata might not have the epic history of the IMSA GTP series, but you sure can’t argue with success. The first Spec Miata was assembled and campaigned in late 1998 by Shannon McMasters, Tim Evans, Danny Benzer, Wally Darbyshire and David delGenio. When it initially ran at some Southeast SCCA events, it was a class of one.

Big things were coming, though: By January of 1999, the Spec Miata class—which was originally McMasters’s brainchild—was adopted by the Southwest Division SCCA, and by July the region was accepting entries.

Fast-forward to today, and Spec Miata is arguably the most popular amateur road racing class in America. Both NASA and the SCCA, the nation’s two largest sanctioning bodies, have Spec Miata classes, and their fields are among the most populous at any given event. At the 2008 NASA nationals, organizers cut off entries at 65 to keep the race from becoming overcrowded.

So, what’s all the fuss about?

Simple: It’s close racing in popular and easy-to-prepare cars. Spec Miata allows any first- or second-generation Mazda Miata built to a rigid set of specified modifications to ensure the equality of all the cars.

In contrast to the Porsche, the Spec Miata is simplicity defined. There’s very little on the car that doesn’t need to be there, and the stuff that remains seems to exist only for the sheer joy of racing.

All Spec Miatas use a specific Bilstein shock absorber fitted with Eibach coil-over springs and Eibach anti-roll bars. Beyond those major items, modifications are very limited and include things like air intake, exhaust, safety gear and some minor gutting.

All cars must run 15x7-inch wheels, and Toyo race tires are required to compete at the national level with any sanctioning body. (Other brands of DOT race tires are allowed in some regions.) So, what you basically end up with is a mildly prepared sports car—which creates some extremely exciting and close racing.

And, unlike the 962, a Spec Miata is as close as humanly possible to being considered affordable in the racing world. We found a few “Spec Miata in a Box”-type kits that included basically everything needed to go racing minus the car—right down to fluids and stickers—for around $5500. Add in a $2500 Miata and some labor and you’re on track for less than $10,000.

If you don’t want to go the DIY route, there are plenty of professional shops that will sell or even rent out a professionally prepared Spec Miata. Of course, prices on pro-built cars can vary with the extent of the rebuild, but we’ve seen restoration-quality builds with top-of-the-line safety gear and digital data packages for less than $30,000. That’s a lot for a Miata, sure, but still pretty reasonable for a professionally built race car of any type. And if ownership isn’t your thing, expect to pay $2500 to $3000 for a weekend of rent-a-ride racing with a topflight team.

What’s Your Point?

Don’t worry, we hear you sitting out there going, “Yeah, yeah, yeah. Nice history lesson. Now how in the living hell are you going to compare a 962 and a Miata? You’ve just been stalling this whole time.”

Well, perhaps. See, the closest comparison really isn’t on the track—even though we have some cool data that we’ll get to in a minute—but in the concept. Both cars were designed to get people on track and racing.

The 962 provided the opportunity for a professional team to go racing at the highest level available at the time, all without having to develop and build their own car. With the Spec Miata, there’s the opportunity for the more “modestly funded” among us to compete on a national level without worrying about the latest trick part or technology that’s only available to a few select teams. Both cars are about creating opportunities to win races for folks who might not otherwise have them.

Sampling the Flavors

Of course, this is all a lot of nice blather without a few good track sessions to back up the bench racing. And when it comes time to wring out a couple of cars on the race track, it helps to have someone who knows what they’re doing. Fortunately, the someone we got was Brian Redman.

To say Brian Redman “knows what he’s doing” would be an understatement of such epic proportions that if we had published such a sentence in these pages, the magazine you’re holding in your hands could spontaneously burst into flames. Lucky for your hands, we won’t.

Remember all of those great cars from racing’s past? Redman’s probably driven them. Yeah, all of them: stints in F1 for the likes of Cooper, Williams, Surtees, McLaren and Shadow; a long history of sports car competition in Jaguars, Porsches (including the 956 and 962), Alfas, BMWs and Chevrons; and now a busy “retirement” that has him vintage racing as well as running his own Targa Sixty Six track events.

With that impressive resumé, however, he’d never driven a Spec Miata. Hmm.

When you need a volunteer to drive a Porsche 962 and a Spec Miata at a race track, a lot of hands go up. Rather than choose from this pool, we went with someone whose hands have been wrapped around the steering wheels of nearly every significant race car of the last three decades. Brian Redman had spent many hours behind the wheels of 962s, but he’d never driven a Spec Miata. Would he be underwhelmed by a car with one-fifth the power?

Our plan was to put Brian Redman behind the wheel of both a Spec Miata and a Porsche 962. The Miata would be provided by Traqmate’s Glenn Stephens, while we’d use a 962 that is campaigned in vintage events by engineer Bill Hawe. A Targa Sixty Six event at Savannah’s Roebling Road would provide the ribbon of asphalt for our comparison of these very dissimilar approaches to a similar problem.

Targa Sixty Six events attract one of the more impressive collections of classic and exotic machinery you’ll ever see on a race track. As a matter of fact, the 962 aroused surprisingly little excitement when it rolled up to the grid, since most of the people present were too busy watching the Porsche 917s and Ferrari 512 BB LMs that were in attendance. The Spec Miata warranted barely a glance from the crowd.

While the more jaded onlookers might not have been blown away by the 962, the considerable thrill has not diminished one bit for owner Bill Hawe. Even after owning and racing the Porsche for a few years, Bill still speaks reverently of his car. “Something must have truly gone awry in the universe that I am able to drive a 962,” he adds. “I can’t believe the racing gods allow me to do this. It is indeed an honor and a privilege.”

Nice to know the luster hasn’t worn off.

Bill’s attitude is understandable, since unlike a Spec Miata, the 962 is more than simply a race car: It’s a living piece of racing history. For this reason it’s tough to put a value on one; when these cars do trade hands, price is determined as much by history and provenance as any other factor. Recently sold cars have ranged in price from about $550,000 to close to a million dollars, so there’s quite a breadth of values reflecting the achievements of the individual cars. Obviously, a former Daytona winner will be more expensive than a backup car that spent most of its life in the transporter. Each will probably be just about as fast as the other, though, so if you can live without the history, you might get more bang from your buck—just a little shopping tip from your pals at GRM.

At our Targa Sixty Six track day, Redman climbed into the 962 first. This was certainly not his first time in one of these cars, and he offered these observations about the 962 experience: “You can’t really see anything behind you, and you’re so close to the front wheels it’s a bit like being strapped to the front of a rocket. Once you get used to driving with the ground effects and the lag from the big single turbo, though, it is really a good driver’s car.”

Owner Hawe echoed Redman’s remarks: “The ground effects really take some getting used to. They allow you to take corners faster than your mind feels should be possible, so you have to have a bit of a suspension of disbelief in faster sections.”

There are also some trust issues that must be overcome with the Porsche. “Getting up to speed can be very daunting,” Hawe said, “because to get up to a speed where the ground effects work properly, you have to have the tires at the proper temperature. But to get the tires to the proper temperature, you have to go fast. It’s a bit of a dilemma.”

A gentle hand is also important when driving the 962. “It’s not the kind of car you can really slide around and bounce off of curbs,” Hawe explained. “The ground effects are very sensitive to ride height. If you nip a curb in a fast corner and change the ride height, all of your aerodynamic grip disappears in an instant. These cars have enough aerodynamic grip to drive upside down at about 140 mph, so losing your grip in an instant is not a good situation.”

Redman deliberately scorched the Roebling Road course with a 1:04.950 lap time in the 962. That equates to averaging more than 120 mph around the 2.2-mile track. Hawe estimates that with gear ratios better suited to the shorter Roebling Road facility, he could shave another second or two from his lap time. Redman’s approach to the Porsche was methodical, businesslike and serious. He said he really enjoys the car. “It’s a very stable and driver-friendly race car,” he told us—but without much of a smile on his face.

Redman’s somber expression was probably not a true indication of the driving experience, but rather more of a reflection on how complex and brutally fast this machine is. Hawe’s car is tuned for about 700 horsepower at 1 bar of boost, and the flat-six engine can last quite a while at that power level. Back in the day, these cars could be aggressively run at around 1.2 bars of boost for about 730 horsepower, with the occasional qualifying-only tweak to 1.4 bars of boost for more than 750 horsepower—maybe more, actually.

As an engineer, Hawe was drawn to the car’s complexity and the way the entire machine works as a single system versus just a collection of parts. He said he appreciates the technical elegance of the 962 and the fact that the car is greater than the sum of its individual components.

That elegance comes with a price, though, and the fee is in a steep maintenance curve. This simply isn’t a “turn the key and go” sort of car. The cold-starting procedure for Hawe’s machine involved Amalfi Racing engineer Klaus Fischer, a laptop, and lots of fiddling with the fuel map. If you’re going to acquire a 962, you’ll probably also need to make a guy named Klaus a mandatory part of your toolbox. Horst or Gunter are equally acceptable.

Klaus Fischer is particularly familiar with the intricacies of the 962, since he helped found Dauer racing. (Remember the guys we mentioned earlier who scored the last major win for the car?) As a result, he knows a thing or two about these Porsches.

Maintaining a 962 is not that much different from maintaining a regular race car—it’s just a bit exaggerated. Fluid changes happen after every race (the sump holds 12 quarts of Mobil 1) and the entire chassis is visually inspected for cracks or damage.

Like most race cars, the most expensive wear item—barring a crash, which we don’t even want to think about—is usually tires. The huge slicks can run upward of $500 per corner. A careful driver can make a set of tires last through a few weekends, though, even with the massive aerodynamic load imparted by the ground effects. Brake rotors can last a whole season, and pads can last several races, which makes sense for a car that was so successful in endurance racing. Overall, keeping a 962 on track is much like keeping any race car on track, only more so.

Speaking of on track, the whole time the Porsche’s crew was messing around with laptops, juggling people, making adjustments, and monitoring data and temps and pressures and readouts from various dials and gauges, Glenn Stephens’s Spec Miata was waiting quietly in the paddock.

Once Redman was done with the 962, he hopped in the Mazda, belted up, turned the key, and headed out to the track. Simple as that. Sure, Stephens might have given him some complex advice like, “When you turn the wheel to the right, the car goes right,” or some such thing, but the overall impression was one of simplicity and ease.

And absolute joy.

Brian Redman might have driven pretty much every car you ever dreamed about in study hall, but he flashed the biggest smile after his first-ever stint in a Spec Miata.

When Redman finally came back after his first-ever stint in a Spec Miata, he was positively giddy. “Well then, that’s certainly the most fun I’ve had all weekend, innit?” he said from behind a giggle. Strong words from a guy who, earlier in the day, had driven not only a 962, but a Porsche 917 as well.

And why not? Spec Miatas are the essence of simplicity and fun: four wheels, an engine and a steering wheel. True to the class philosophy of getting folks on track, this particular car was Stephens’s first-ever race car. Back in 2002, he went to his first driver’s school in his recently built, 275,000-mile Spec Miata. The engine didn’t last much longer before it was rebuilt, but the transmission survived another 5000 race miles before it was redone, mostly out of guilt.

We spoke with our Spec Miata owner about the typical weak spots of these cars, and our conversation sounded a lot like this:

Us: “So, what breaks on these cars? What do you find yourself fixing every weekend or carrying lots of spares of?”

Stephens: “Uhh, hmm—not much.” [pause] “So, how you guys been?”

And that’s pretty much the appeal. Spec Miatas, in addition to being fun and offering huge fields with tons of competition, are also extremely bulletproof. Stephens figures he goes through a set of tires every two to four weekends at $600 total, and he changes front brake pads about as often at $125 per set. Beyond that, drivers mostly need to worry about hitting something.

Of course, none of this math really seemed to matter to Brian Redman, whose businesslike demeanor around the 962 had been replaced by the goofy grin of a kid who had just gotten his first kiss. “You can just do anything you want with it,” he said of the Miata. “It just sort of zips along, and as long as you keep the momentum up, it just keeps flying around the track.”

Redman was about 20 seconds a lap slower in the Miata than in the 962, but he seemed to be passing just as many cars when he was on track—a testament to the friendly nature of the Spec Miata.

Both cars put sticky rubber on the ground, but the Porsche 962’s already prodigious mechanical grip is augmented by hundreds of pounds of aerodynamic downforce. While the Spec Miata can be driven a bit “loose” and slid around without much of a speed penalty, the 962 requires a precise and controlled line so as not to upset the delicate aerodynamic balance.

The rampant popularity of the class has another side benefit: It makes people better drivers. When we talked to Stephens, he reported that since our test day he has beaten Redman’s time by more than two seconds. “And it’s really the same car, when you think about it,” he adds. “Most of the extra speed has just come from small development tweaks, but mostly from guys just constantly pushing each other to find that last little bit of speed from skill.”

End of the Day

Now, the last thing we want to do here is come across like we’re slamming the 962— we’re not. Every millimeter of that car has been designed for speed. Every molecule of aluminum, fiberglass, plastic or steel is where it is for a reason.

The Miata? It’s just fun. There’s really no better way to explain it.

Bill Hawe describes 962 ownership as more of a “stewardship.” He feels—and we tend to agree—that the owners of these cars should respect their history by preserving and maintaining them. It’s as much engineering art as it is a race car.

These cars couldn’t be more different, right? Well, if you consider their missions in life, there are a lot of similarities. Both the Porsche 962 and Spec Miata have helped legions of racers get on track.

But if the 962 is history, the Spec Miata is history in the making. This Porsche transcends car-ness by being art, and the Spec Miata does so by being part of a phenomenon.

Both are icons, and both deserve to be appreciated for their contributions to our sport. Both give folks the chance to go racing, and our world is better because of them.