A great race driver adjusts to the unique

variations in each race. He is both an

offensive and defensive player simultaneously. He is both hunter and prey. He must

know when to follow and when to attack. He

must assess the strengths and weaknesses of

each competitor. He must be an expert at psychological warfare.

Proficiency in passing is a skill that reveals a driver’s true greatness. Given a clear track and enough time in a quality race car, almost

any solid driver can turn in a quick qualifying lap. The far more difficult task is to maintain momentum in traffic.

The Straightaway Pass

The most simple pass, by far, is the “draft and pass” on a straight. If

you are fortunate enough to have superior power, this pass is easy:

You simply come off the corner cleanly, push hard on the right pedal,

draft for a few seconds and then cruise on by.

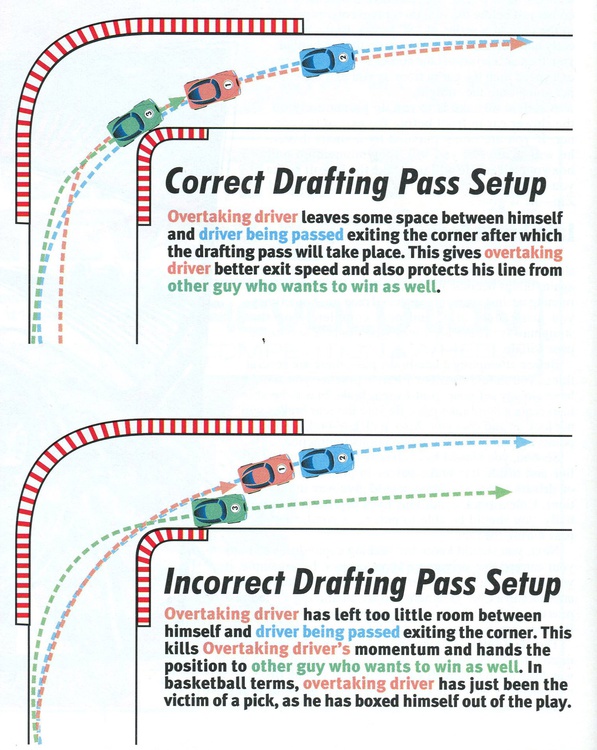

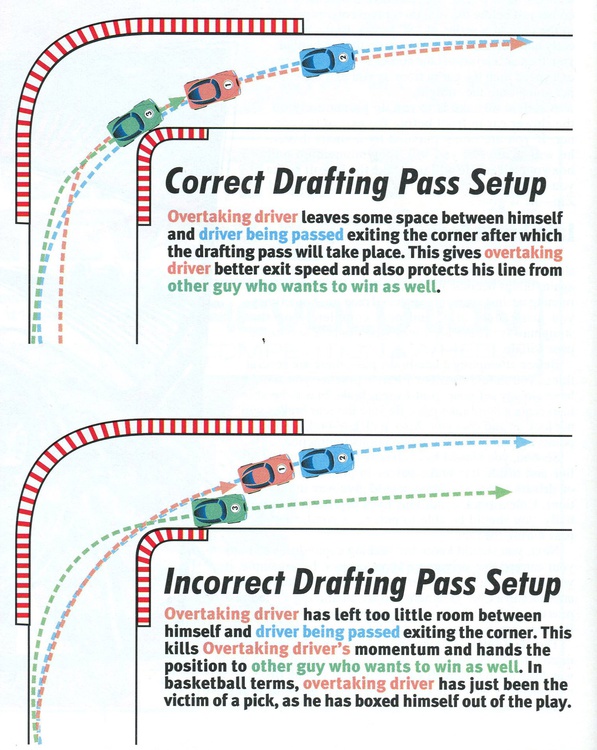

If you have a more evenly matched race car, this pass is a bit tougher.

First, you need to lay back slightly as you enter the corner, then accelerate and run up on the car in front as you exit the turn. Next, you must

draft a little longer on the straight, then pull out and pass when you

have enough momentum to get by cleanly.

Here is an important footnote: If you have someone pursuing from

behind as you are attempting to set up this pass, it complicates matters. On most tracks, you can take a defensive line as you enter the

corner just before the straight (or two corners prior

in the case of a series of “S” turns). Brake a tad

early and close the door cleanly on the car behind

you, then accelerate off the corner to achieve more

exit speed than the car in front as you exit the corner going onto the straight.

A rookie mistake is to run up prematurely on

the slower car in front before the exit of the corner. If you are being pursued by a smart driver,

he will gladly let you kill your momentum and

box yourself in. He will then take the lay-off space

you gave him and use it for superior exit speed.

Zip—he is gone!

Late-brake Pass

While you may be able to draft and pass slightly

slower cars on the straightaway with relative ease,

again, things become more complicated when you are

running against an evenly-matched race car. Sometimes

you just cannot draft and pass completely on the

straightaway. There are times when only a late-brake .

pass will do.

Before attempting a late-brake pass, there are several

things you should consider. First, in practice you should

have already set your front-to-rear brake bias to be able

to execute a late-brake pass. Be sure the rear brakes will

not lock up and spin you. Also, pick late-brake reference

points as well as normal brake points in practice.

Second, you should have already tried a couple of off-line and inside-late-brake passes in practice (preferably

on drivers whom you knew would give way in this situation). Unless track conditions have deteriorated substantially, you should be able to pull off a similar late-brake

pass during the race.

Next, you should know the braking capabilities of both

your car and the car you are about to pass. For example, if

you are running in the latter stages of a street stock endurance race in a Chevy Camaro and are attempting a late-brake

pass on a lighter BMW, you may have a problem. The lighter

Bimmer may have more brakes left.

The ideal solution to the above problem is to take the Camaro into the corner as deeply as you practically can while

watching the BMW with your peripheral Vision. (You are simultaneously watching the apex of the corner with your primary vision.) The key is to adjust to the BMW’s reaction to your pass attempt with your braking.

Do not let the BMW take you into the corner any deeper than you can handle. In addition, try to keep your nose clearly alongside

the BMW. The driver of a lightweight BMW

will think twice about slamming the door on

a huge Camaro. Your ace in the hole here is

that the BMW driver probably knows the laws

of physics as well as you do. If he is smart, he

will know that you have the upper hand

Passing in the Rain

If you practiced in the dry and you are now

racing in the rain, all bets are off. As you know,

rain lines are different from dry lines. The classic line will probably be too greasy and too

tight in the rain. Your best bet is to brake

smoother and take a gentle, sweeping radius

through the corners. Also, break off your draft

earlier when passing and be sure you are

clearly inside of the car you are overtaking.

Close drafting is dangerous on a wet track.

If the driver in front brakes early, you may hit

his rear end. It is better to be inside of an early

braker as you enter a corner in the race. Also,

only a fool would challenge you from the outside of a corner in the rain.

Passing Setup Techniques

As many different road racing rulebooks

state, the responsibility for a safe pass rests

with the overtaking driver. Thus, a world-class

mirror driver can make life difficult for you.

As you attempt to dive under him for a late—

brake pass, he seemingly anticipates the pass

and takes a very defensive line to block. While

overt blocking is illegal in road racing, it is

hard to recognize from the sidelines; thus

blocking rules are rarely enforced.

One of the most frustrating experiences in

racing is having to follow a mirror driver for

five laps before he finally makes a mistake

and you can get by. Fortunately, over the years,

I have found a few techniques that will help

you in this situation.

At the first indication that the driver in front of you is overtly blocking, shake your fist visibly in the air, then point at the offending car as

you stare at the flagmen in the very next comer. It this does not produce a blue and yellow

passing flag really soon, it is time to move on to Step B.

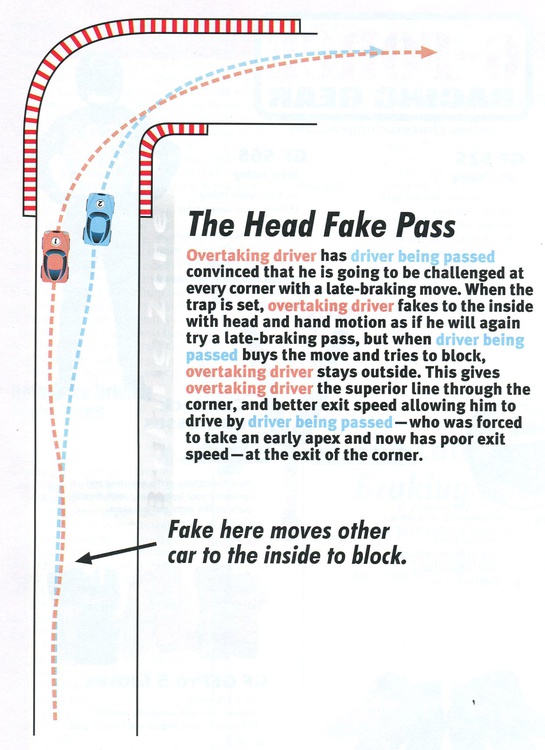

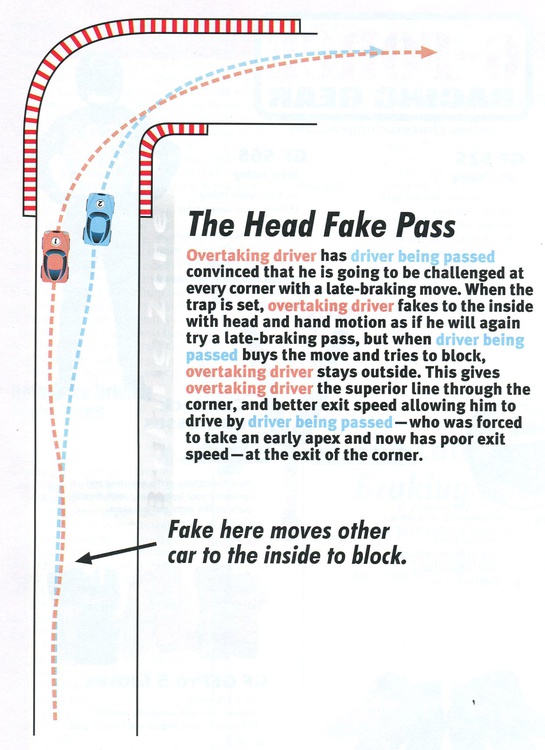

Step B is to pressure the blocking driver into late-braking situations at every possible chance—especially in tight corners. Let him think you will attempt a late-brake pass at any moment.

Make him early apex every corner to protect his line. When he is convinced that this is your

plan, set him up for a corner leading onto a long straight.

Just before this corner, use a “head and hand fake” to the inside, forcing the blocking driver

to move to protect his line and apex early. If you are entering a right turn, hold the steering

wheel by its left spoke with your left hand, making sure the car stays on a straight braking

path. Quickly tilt your head to the right and slide your right hand over the wheel to the right.

Of course, your right hand is really not turning the car to the right, but any self-respecting

mirror driver will move his car to thwart your late-brake pass. (Note: This technique works

better on closed—wheel cars than formula cars. Formula car drivers are not likely to fall for this

ploy as they key off the directional change of the front wheels—not hand or head movement).

Next, move slightly to the outside and take the blocker deep under braking into the corner.

If he bites, which he probably will, he will glide across your bow and you can pass behind him

as he tries to save his car from leaving the track. If he checks up, realizing that he has been had,

he has in essence relinquished the fast line to you. You are obliged to take it immediately. You

cannot hesitate, or someone is going to get hurt. Final note: As with all passing situations, this

one is not 100-percent foolproof. Before trying it, you must know the radius of the corner, the

track surface, the track exit width and your own ability to react.

Brake and Park Pass

Step C is the what I would call the “brake and park pass.” You have played by the rules;

however, let’s assume you have given the comer workers an opportunity to give the blocker a

passing flag and that you have already used various psychological techniques to get by the

blocking driver, with no results. Time to move on the blocker.

Blockers are snivelers. After the race, they will say that they changed their line to an early apex (ie: blocking line) because “my car got loose” or “I just made a

few driver errors.” Well, if they can make a mistake, so can you. The

“brake and park pass” is just one of those unfortunate late-braking

mistakes you, too, might have to make.

Even the best mirror driver cannot convince race officials that he needs

all of the track, all of the time. Moreover, he has to leave some space on

the inside, or you will go around him on the outside. Sometimes you have

to take that meager piece of asphalt inside and use it. Even if the line looks

horrible, it will look better as you get closer to the comer apex-especially if you miss your brake point and go in too deep. (Oops!)

The “brake and park pass” requires good car control skills, since the

back end of the car will probably step out (oversteer) on you as you enter

the comer under extreme late braking. If you do not have these skills, do

not attempt this pass.

Incidentally, I am making a

strong distinction between “slamming” and “parking” here. Park-

ing usually means you simply

made an aggressive late-brake

pass, taking the best line and much

of the corner exit away from the

blocker. Slamming means you laid

so much metal on him that you

launched him into an Armco barrier. The purpose of the “brake and

park” is to pass and move on, not

to destroy a competitor’s race car.

Defensive Driving Techniques

It may seem incongruous that I

am discussing defensive driving

techniques just after I assailed

drivers who drive with their mirrors. While the difference between

a blocking driver and a defensive

driver may seem imperceptible, I

assure you there is a substantial

difference between the two types

of drivers. Moreover, defensive

driving is as important a part of

racing as passing. It is the other

side of the same coin.

Here is how I make the distinction between “blockers” and “defensive drivers:”

• A blocker is generally inconsistent, slow through the corners,

has weak technique and hurts your

lap times substantially when you

encounter him. You know that

once you get by him, you will

leave him in the dust. He deserves

little respect.

• A defensive driver has excellent skills. He is consistent and

quick through the corners. He does

little, if anything, to hurt your lap

times. You may even wonder

whether, if you do get by him, you

will be able to pull away. He is a

driver you can respect.

The Best Defense is a Good Offense

Skilled defensive drivers use a fast, consistent line and do not use

their mirrors to excess. They are confident that they can get around

the track as fast as anyone and they do not need to resort to blocking

to keep a competitor behind them.

Good defensive drivers are also proficient passers. They can pass

almost anywhere when their car is well set up and running right. They

think ahead, planning their next pass just after they have completed

their previous one. Thus, on defense, they can predict where and when

the driver behind them is most likely to pass them.

Discretion is also part of being a good defensive driver. It makes

little sense to slam the door on a car that’s coming up fast and is about to lap you. Moreover, it rarely makes sense to keep a car

behind you that is much faster on the straight. If anything, use that

car as a drafting tool. Let it help you work through traffic. Then,

repass it in the closing stages of the race. Drive defensively only

when it counts for position.

Defensive Driving in Close Contests

There are situations in which you and the car behind you are locked

in serious combat. Your cars and your driving skills are so closely

matched that you know you cannot let the other driver pass. This is a

classic offensive/defensive driving battle.

First, remember that you are in front and you have the better track

position. Next, do not obsess over the driver behind you. Yes, you can

use a slightly earlier brake point

or take a slightly earlier apex on

occasion to disrupt the rhythm of

the driver behind you. However,

do not lose sight of the fact that

it was fast, consistent laps that

put you ahead of your nemesis

in the first place.

Next, try subtle tactics to determine your rival’s talent and

experience (unless you already

know he has no weaknesses—

then just drive fast and smooth).

In a car with brake lights, you

can use left-foot braking to determine whether your challenger

is driving his own line or keying

off yours. By using left-foot

braking and a slight brake check

in the brake zone before the corner (just enough pressure to trigger the brake lights), you can find

out if the driver behind you is a

hawk or a vulture.

Left-foot brake lightly and

early as you continue to accelerate with your right foot as you

move toward the corner. If the

driver behind you brakes heavily

and keys off your brake lights,

he will drop back way before the

corner. He has shown himself to

be a vulture. He is scavenging off

your line and brake points. This

guy can be had.

If, on the other hand, the driver

behind you closes up on your rear

bumper, then you are dealing with

a hawk. He is a confident racer who

knows the right line and brake

points. He was waiting for you to

make a mistake. Hold him off going into the comer and do not brake

check him again. You have a battle

on your hands.

The only tactic that I have eve

found to work consistently on a

hawk is to take him out as fast as

you can and challenge his ego.

If you are confident that you can drive on overheated tires better than

he can, push the envelope. It is a calculated risk, but he may bite. If

you find him laying back, even just a little, give up the ploy. He is

waiting for you to cook your tires and then he will make his move.

This guy is smart.

Sometimes you get a gut feeling that a hawk is waiting for the last

one or two laps to make his move. Usually your gut feeling is right.

He will make his move late.

No strategy works all of the time. However, on the second-to-last lap, you may want to take away your pursuer’s first option by

slamming the door hard on him if he tries a late-brake pass to the

inside, for example. This limits the hawk’s option to a one-shot,

last—lap pass in a corner that is probably his second choice. Suck it up and drive as fast as you can for the last lap. Chances are, your

pursuer will not be as confident he was on the prior lap. Of course,

I have been wrong before.

One final defensive driving technique is what I call the “late-brake

booty shake.” I saw it a number of times before I trained myself to

recognize it and to react appropriately to it. I have even seen the “booty

shake” work in both CART and F1.

The “booty shake” is best used entering a series of tight turns where

overtaking is difficult. It relies on surprise and the quick, instinctive

reactions of a good race driver who is in hot pursuit. Its execution

goes something like this:

1: As the race is winding down, the driver in front appears to be

driving into corners a little bit deeper in order to hold off the guy

in pursuit.

2: Seeing that the driver in front is pushing the envelope a bit

too hard, the driver in pursuit moves in closer to take advantage of

any mistake which will allow him to pass. The driver in pursuit

may be convinced that it is his driving talent that is causing the leader’s minor miscues. The lead

driver is counting on this.

3: Entering the braking zone before

the “S” turns, the leading driver appears to take a moderately defensive

line and proceeds to execute a relatively late brake.

4: The rear tires of the first car lock

up slightly. This leading formula car

starts the “booty shake” from left to

right, taking up the whole track as the

it approaches the “S” turns.

5: Reacting to avoid a crash into the

rear of the car in front, the second

driver Climbs on his brakes, locking

up his fronts, which forces him into a

mild understeer.

6: Miraculously, the driver in front

has recovered and is hard on the gas

through the “S” turns and off like a

rabbit! The panic stop and momentary

hesitation by the pursuing car has left

too large a gap for him to close in the

remaining few laps.

Was the “booty shake” a driving error or a planned strategy? You make

the call.

The Art of Passing

A professional race driver who

says he does not have a mental book

on passing or defensive driving

techniques is stroking you. Some

drivers are great at blocking. Others are good at Sucking unsuspecting rookies too deep into a corner

and showing them the gravel pit.

Some are experts at running a competitor out of tires before they pick

him off. A few use their late-braking talent and reputation as a wild

man to intimidate other drivers off

the line.

When it comes to passing strategies, there are an infinite number of

combinations and permutations. No

single driver can know them all. What

makes the art of passing so intriguing

is that certain techniques only work

on certain drivers. You need to know

the personalities of the drivers you

race with just as well as you know

your skills.

Disclaimer

The above driving techniques have

been found to be successful for the author in many but not all situations. They presume the knowledge of proper

advanced race driving techniques and an advanced race experience level.

They may or may not be successful for a driver depending upon his or her

training, experience, car control ability, mental state, physical condition

and response time. Moreover, the effectiveness of the techniques discussed

are further limited by the preparation and fitness of one’s individual race

car and those of one’s competitors, as well as track design, track conditions, sanctioning body rules and reactions by another competitor.

Hence, GRM and the author disclaim liability for any or all

damages, injuries or other consequences arising from the use

of any and all techniques discussed herein. In other words, if

you choose to use these techniques, you do so at your own risk

and assume all liabilities for yourself, others and any and all

consequences in doing so. Under no circumstances are these

techniques to be employed on the street or in any non-race sanctioned event where full racing safety harness, Snell-approved

racing helmets, fireproof apparel, roll bars, and

all other proper safety equipment are not required.

This article is from an old issue of Grassroots Motorsports. Get all the latest how-tos and stories for just $20 a year. Subscribe now.