Old advertisements for Baldwin's unique air throttle. It's worth noting that the ad refers to it as Baldwin Locomotive Works, so this is before they absorbed Lima-Hamilton and became Baldwin-Lima-Hamilton. Also, Westinghouse's name shows up prominently. Much like how Alco allied with Macintosh-Seymore for engines and GE for electrical components, Baldwin used De La Vergne diesel engines and Westinghouse electrical gear. While GE electrical systems were the best of the best, Westinghouse's were a very close second. Westinghouse chose to ally themselves with both Baldwin and Fairbanks-Morse, and despite the flaws of both those manufacturers, the Westinghouse generators and motors had a reputation for durability and lugging power.

While Alco, EMD, Fairbanks-Morse, GE and Lima-Hamilton all settled on a traditional 8-notch electric throttle (If you ever hear an engineer say he "had it in Notch 8" that means WOT) from the beginning, Baldwin designed their own unique pneumatic throttle, which had, I think, 32 settings. It also had a unique "Soft Start" feature that basically functioned as a form of traction control. You yanked the throttle wide open and it would bleed off pressure when it sensed wheel slip until the wheel slip stopped and then begin applying the throttle. As described:

The brain of a Baldwin diesel is its throttle.

At first glance it may appear to be just a simple affair of an air pipe directly plugged into the governor fuel controller. In fact, the throttle performs many different functions all at the same time, and it is paired with a complex set of governor and electrical controls.

In addition to the standard running controls that work as a direct input/output on the diesel engine, a special Soft Starting feature is included on most Baldwin diesel locomotives. The soft starting feature is an extension of the main generator load control system that is operated by the exciter. A variable resistor, controlled by a special set of pneumatic relay valves, limits the generator output in the moments after the throttle is opened.

As soon as the throttle is switched "On" and power is applied, this resistor is set at it's maximum setting, and keeps the exciter and generator fields so week that they virtually don't exist. After a second or two, the air pressure acts on the resistor to lower it's resistance, thereby allowing the fields to strengthen and the generator output to increase. After a few more seconds, the air pressure holds the resistor at it's minimum setting so that full power can be applied.

When the throttle is closed, the air pressure vanishes, and the resistor resets to control another soft start. This resistor is also connected to the wheel-slip relay. When the wheels start to slip, the relay opens a valve that lets some of the air pressure to bleed off, which in turn acts to weaken the generator field and output with the same effect as reducing the throttle.

In a way, you can let the locomotive start itself with this system. Even if you cranked the throttle wide open as fast as you could, the engine would load up soft and easily, starting off with a gentle push before digging in and really starting to shove. Then when the power came up and the wheels started to slip, the load controller would automatically regulate power output to keep wheel-slip to a minimum.

Just tell her what you need and she'll do all the work for you!

Early on, this unique throttle was not an issue, as the market was just switchers and cab units. Switchers typically operated by themselves and did not need multiple unit capability (MU is hooking multiple engines together and controlling them all from the cab of 1). And in the era of cab units, railroads were not mixing and matching motive power. If you had a job that had required a 4500hp articulated steam engine, you bought an A-B-A set of 1500hp cab units and ran those. But as trains began to vary in length and railroads aqcuired more and more diesel power, they began to intermingle units. Now instead of just A-B-B-A sets of EMD F3s, you might have two F3s sandwiching a pair of Alco RS3s. And since every other manufacturer had settled on the same throttle setup, they played nice. But Baldwin retained their air throttle, convinced of it's superiority. And the air throttle was not compatible with any other manufacturers. So if you needed more power on a train being hauled with Baldwins, you either had to lash up more Baldwins, or you had to have a crew riding in whatever other motive power you hooked up and try to coordinate operation. And even if you had an all-Baldwin consist, it's rumored that once you get over 4 units, the throttle got increasingly less and less responsive. Later on, Baldwin would offer an electric throttle that was MU-compatible with others, but it was an extra-cost option.

This, on top of so-so reliability from the De La Vergne engines and the lack of dynamic braking, meant that railroads became increasingly weary of Baldwin units. Also not helping was Baldwin's refusal to standardize, instead chosing to build diesel locomotives like they had steam locomotives. Out of the same batch of locomotives that a railroad ordered of the same model, they might find air lines routed differently, different colored wiring, circuit breakers in different locations. And they offered a dizzying array of models that was not helping things either. Over at EMD, they offered an SW switcher, two cab units (the B-truck F-series passenger and A1A-truck E-series passenger, with similar bodies) and two road switchers (the B-truck GP-series and the C-truck SD-series with similar bodies). Baldwin, meanwhile offered cab units with 2 different horsepower ratings, two different truck options (B and A1A) and two different body styles. Similarly, their DRS road switchers came in 2 horsepower ratings, three different truck options (B, A1A and C). And there were freakish locomotives like the 12-axle Centipedes and huge 2000hp transfer locomotives. And Baldwin would also do custom builds, like a single-engined 1000hp DR-series with only one powered truck for C&NW or double-ended DR-6-4-2000s for Jersey Central. They cannibalized sales from each other and cost more money to offer all of these different locomotives, and all sold poorly.

The irony is that Baldwin left the market just as they started to get a hang of it. They simplified their lineup drastically in '50. The only cab unit was B-trucked, 1600hp RF-16s. Their road switcher line was pared down to the AS16s, which were all 1600hp units (although they continued offering 3 different truck options) and the RS12 which was a 1200hp branch line unit. They did continue to offer one oddity, the 2400hp center cab RT624. They got rid of their extensive option list, made dynamic brakes available on all of their offerings, and introduced the optional electric throttle that made them play nice. Their RF-16s and AS16s outsold their predecessors strongly (although still not sales giants). And then Westinghouse, who had taken over B-L-H, decided that they no longer wanted to pursue wholesale production and instead wanted to just sell componentry to manufacturers, and pulled out of the locomotive production.

The Monon, I admittedly don't know much about. The only things I really know about the Monon was that that wasn't the railroad's real name, they had a pretty nice gray, red and white passenger scheme, and they once bought some big Alco C628s and then freaked out when they discovered they were pounding the daylights out of their roadbed and sent them back to Alco C420s. I assume they were swallowed up by either Union Pacific or Chicago & Northwestern. (Nope, looked it up, Louisville & Nashville in '71)

The EMD BL2 is an interesting one. It's both an important part of EMD's evolution and a rare misstep by early EMD (the RS1325 and the TR6 being the other two). At that point in time, EMD's FT had broken the back of steam locomotive and the concept that diesel locomotives were just a novelty, the F3 had hit the market to resounding success, their NW and SW switchers were swarming yards and their E-units by far outsold the competition. Alco was their closest competitor and was still relatively healthy, GE was just off making a number of tiny switchers, while Baldwin was still producing steam locomotives and barely dabbling in diesels, Lima had just wrapped up steam production (they were actually still trying to market a 4-8-6 but no railroads bit) and was making a half-hearted attempt at diesels and Fairbanks-Morse was barely a blip on the radar.

The F- and E-units had their success, but there were complaints. If you wanted to run them someplace where there was no turning facilities, you had to run a back-to-back A-A pair, because there was no visibility, and that was overkill. They were also a pain for switching manuevers, again due to lack of rearward visibility, as well as lack of platforms and walkways. And there were structural and maintenance concerns due to them being monocoque construction.

The BL2 was mechanically the same as an F3, as EMD knew not to mess with a good thing. It still used a carbody, but it was now body-on-frame. They narrowed the body in back to give it better rearward visibility. And they added platforms on the front and rear for brakemen to work from. But the downside was, it still didn't have walkways, so crews had no easy to get to the front and rear short of going through the inside. The narrower body made access and maintenance just as difficult as an F-unit, if not more so. And the frame design was weak, so when used in M.U. to haul heavier trains than a single BL2 was meant to haul, they developed frame troubles. And then, there was the styling, which many considered homely and muddled. Still, the BL2, for its flaws, showed EMD the direction they needed to go: Narrow non-structural bodies on a frame, walkways and platforms, good forward and rearward visibility.

It is odd that EMD went the direction they did, as Alco had come out with the RS1 in 1940 and the RS2 in 1946 and had defined the road switcher market. So why didn't EMD follow the existing blueprint? No one really knows. Perhaps it was a sort of pride? They made the diesel market what it was and didn't want to be perceived as copying a competitor maybe. Not really sure. Either way, they paid for it, with only 1 BL1 and 58 BL2s made, compared to 456 Alco RS1s and 386 Alco RS2s.

Wait, what was that I mentioned about a BL1? There was indeed a BL1. A single one. And that's a weird controversy. In '48, EMD built Demonstrator #499, which they labeled as a BL1. And cosmetically and largely mechanically, it was identical to a BL2. In '49 they converted it to a BL2 and sold it as such. So, what was the difference? EMD insists it was that it did not have M.U. capability and that when they added that, it was now a BL2. But photos show #499 having M.U. connections before its conversion to a BL2 and records show that the BL1 actually used a pneumatic throttle (not unlike a Baldwin) and then was converted to a standard throttle when it become a BL2. Why there is this discrepancy between GM PR and the truth is unknown.

I find them historically interesting and cosmetically funky. I also think it's interesting that some purchasers purged theirs from the roster pretty quick while some like Western Maryland and Bangor & Aroostook held onto theirs for a while. Bangor & Aroostook still had their BL2s in operation (as well as some F3s) until the ceased operation in the 1990s.

Here is a different shot of WM #82 . I posted a shot of it on the previous page. I find these BL2's to be a bit odd looking. The F units look great. The GP and SDs are pure function. This thing is like an art deco cross between the two.

In reply to Wally (Forum Supporter) :

There was actually one of them in that podunk town in NY or PA when we were crewing for the rally team. Honesdale, or whatever it was. I spotted it when we were getting fuel and then went to that bar for lunch. I think it was Stourbridge Line's.

In reply to T.J.:

They are definitely strange, but you can see the evolutionary line of thought. Like I said, its strange that EMD went that route when Alco had already come out with the RS1 and RS2 to pretty solid success.

1 railroad, 4 BL2s, 3 different paint schemes. This was taken in '85, and while it looks like they've parked the two in solid blue, the other two are still in operation. BAR was kind of like an operational EMD-themed railroad museum.

An F3 followed by a BL2 followed by an F3 followed by 2 more BL2s. And, this being the Bangor & Aroostook, I'd wager that those boxcars they are pulling are full of potatoes.

I'm really enjoying this thread. I don't have the time to read it in the detail that it deserves but I'm enjoying skimming and looking at the pictures.

I have a question on the early diesels. Where there ever anywhere the engine drove the wheels mechanically or did they go straight from steam to diesel electric?

In reply to NickD :

I've never heard of the Bangor & Aroostook before, but it sounds like a fictitious model RR name that someone made up, then they decided to name a real railroad after it.

In reply to APEowner :

I think the Budd RDCs could power the wheels from their diesel engine, but they were not locomotives in the normal sense of the word since they didn't pull trains.

The BL2 was not the last of the BL-series either. In 1992, EMD's light-duty GP15-1 and GP15T had been discontinued for over a decade and they noticed that many railroads were overhauling old GP9s and GP30s in their own shops. Thinking that A) there might be a market with shortlines and B) railroads might prefer to buy rebuilds right from EMD. When Burlington Northern was planning to overhaul some GP9s, they approached EMD and they came up with the BL20-2.

EMD took 3 GP9s (one of CB&Q heritage, one of Northern Pacific and one of Spokane, Portland & Seattle) and converted them. The 567C V16s had their "power assemblies" (rods, pistons, liners and heads) replaced with 645 power assemblies (bumping them from 567ci a cylinder to 645ci). They also stripped off the Roots supercharger and installed an odd centrifugal supercharger/turbocharger hybrid. It was driven off the front gear drive, acting as a supercharger, but it still retained the turbocharger exhaust-driven impeller, so that at high speeds, the impeller reduced the horsepower needed to drive the supercharger. These changes modernized the engine, improved fuel efficiency and bumped horsepower up from 1750hp to 2000hp. They also installed a newer generator and Dash-2 electrical. And the body got completely overhauled, with a short hood, a new cab and squared-off GP60-style dynamic brake assembly in place of the old tapered style. The GP9 frame, tanks, traction motors, trucks and controls were all reused.

A GP9 as originally built, to compare

Like the BL2 before it, the BL20-2 was not a success. After building the first three for Burlington Northern, Burlington Northern instead decided to have their GP9s converted to GP28Ms by MKRail, Morrison-Knudsen's railroad division, and left the three with EMD. EMD painted them up in demonstrator colors and toured them around for 2 years, but no other BL20-2 orders ever materialized and EMD ended up giving them to a leasing company, who still operates them today.

The BL20-2's big failure was it was just too expensive (although MKRail's rebuild for BN wasn't cheap either). EMD's overhaul was perhaps too comprehensive. Most railroads didn't care about all-new cabs, or new long-hoods with updated air filters and dynamic braking grids or a funky turbocharger/supercharger setup. Mostly they just wanted a chopped front nose and Dash-2 electricals and the 645 conversion but still with the Roots blower. Since they were designed to be used for light duty work, the extra 250hp wasn't that necessary. And while they were more fuel-efficient, the GP9 was not a particularly thirsty locomotive to begin with, so it would take a long time for those fuel savings to recover.

Mostly, it was just that the branch line market was never what manufacturers seemed to think it was. Every attempt at a "branch line" light duty locomotive was a sales flop. EMD's BL20-2 and RS1325, Alco's RSC-series and C415, GE's "Baby Boat" U18Bs and U23Cs, Baldwin's DRS-4-4-1000s and RS12s. Most large railroads were content to just shove old outdated equipment, maybe with a mild refresh, onto branch line service for light duty. Short line and regional railroads preferred the option of buying cheaper old Class 1 castoffs than shelling out big money for shiny new locomotives or pricey rebuilds.

Here is a shot that shows the driveshaft. Driveshaft and u-joint were from Spicer. Which makes some sense since the RDCs were more like busses on rails in some ways than they were like train locomotives.

Pete Gossett (Forum Supporter) said:In reply to NickD :

I've never heard of the Bangor & Aroostook before, but it sounds like a fictitious model RR name that someone made up, then they decided to name a real railroad after it.

They were up in Northern Maine. Big potato hauler. The railroads it was formed from were even wackier sounding: The Bangor & Piscataquis Railroad and the Bangor & Katahdin Iron Works Railroads. It closed up in the early 2000s, then its tracks were used for the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic, with part of it going to the Maine Northern Railway. Then the MM&A went bankrupt after the Les-Megantic derailment disaster and the line became the Central Maine & Quebec Railroad

Here is a picture of an RDC truck. You can see where the driveshaft enters. These had disk brakes and torque converters which is not normal for railway equipment.

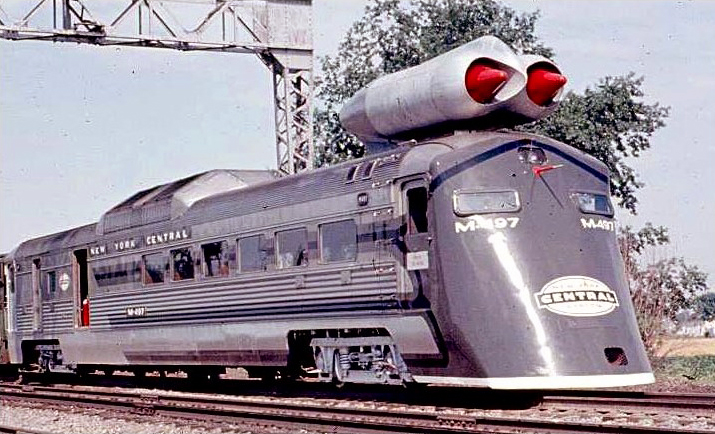

Nick, if you have the info, please post something about NYC's jet-powered RDC M-497 that still retains the US railroad speed record.

APEowner said:I'm really enjoying this thread. I don't have the time to read it in the detail that it deserves but I'm enjoying skimming and looking at the pictures.

I have a question on the early diesels. Where there ever anywhere the engine drove the wheels mechanically or did they go straight from steam to diesel electric?

Europe used a lot of diesel-hydraulics, where the diesel engine turns a hydraulic transmission. Alco built some for the Southern Pacific, and Krauss-Maffei imported some for the SP as well, but they were troublemsome and didn't hold up and there were delays when parts were needed and they gave up on the whole thing. As a whole, things that the Eurpoean railroads have no issue with, quickly tend to get beat to E36 M3 in North American use. North American railroading is some of the harshest, most-brutal conditions out there.

Plymouth and Davenport and Whitcomb (who made a lot of tiny industrial steam locomotives) all built gasoline-mechanical switch engines, with a mechanical transmission between a gasoline engine. But that was pretty small stuff, mostly used for shuffling an engine in or out of a shop, or moving a single car around an industrial complex. Similar to RDCs, there were also "Doodlebugs" early on, which were a self-propelled passenger car that might tow one other car, and typically were gasoline engines with mechanical transmission.

In reply to NickD :

Am I correct in thinking that the Brookville BL20 is a derivative of the EMD BL20? I see the MN BL20s running occasionally, and they sure look similar to the EMDs.

In reply to 02Pilot :

I think any resemblance between the BL20-2 and the BL20GH, in appearance and name is coincidental. The BL20GH is a ground-up new locomotive (not a rebuild) and uses a low-emissions Detroit V12, Kato generator and Caterpillar traction motors, designed for passenger usage

M-497, aka The Black Beetle, was really just one silly publicity stunt. In 1964, Japan had begun the operation of their first high speed rail system. There was much publicity over the Shinkansen, and the American public began wondering "Why can't we have that?". The railroads knew why: Japanese railroads were government owned and operated and their roadbed was maintained to a uniform standard. American railroad infrastructure varied railroad-to-railroad (and even between divisions on the same railroad) to suit their needs. For example, little Central Vermont wasn't going to shell out a fortune for perfectly-leveld roadbed with the heaviest rail when they weren't going to use it. You couldn't run coast-to-coast high-speed rail, because you would have issues where you transitioned from line-to-line. Also, it would require construction of new routes where they crossed mountains or had tighter curves or through-city routes. The only US railroad actively pursuing comparatively high-speed rail was the Pennsylvania, who was busying building and upgrading their Northeast Corridor so that they could send GG1s at a routine 100mph.

New York Central had earlier experiemented (unsuccessfully) with both the Baldwin RP-210 Xplorer and the GM Aerotrain, trying to find an edge and stop the hemmorhaging of revenue from passenger service.

So in 1966, the Central decided to do a study on the stress and impact of high-speed service on existing track and infrastructure. They picked the tracks between Butler, Indiana and Stryker, Ohio as they were arrow straight for miles and in very good condition. The track was unmodified for the test. They then pulled a Rail Diesel Car out of service, yanked the diesel engine and drivetrain out of it and built a shovel nose for it to somewhat improve it's brick-like aerodynamics. Then they took a GE J47-19 jet engine off a B-36 Peacemaker and welded it to the car. On July 23, 1966, they closed off the all of the overpasses off the track, had the police cordon off all grade crossings, and then fired it down the track a few times. Due to the lack of drivetrain, it had to be towed back to the starting location after every time. It went a top speed of 183.68mph, which is still the current US speed record, before the engine shut off and failed to restart. An effort was made to get it fired again, but was unsuccessful, and the NYC had already collected all the data they needed, so no further tests were performed.

The engines were stripped off the roof and M-497 was restored to as-built condition and put back into usage, where it served a normal career until Conrail retired it in 1977 and scrapped it. The engines were fixed and installed as a snow-melting rig called X29493. Like similar jet engine snow blowers, it worked at clearing snow and ice, but was also quite adept at blowing the ballast away too, and was eventually scrapped.

The data that the NYC gathered was pretty much ignored. Basically they knew that high speed rail wasn't particularly viable. Also, they were busy working on their merger with Pennsylvania, who was busy developing the Metroliner high speed electric trainsets for the Northeast Corridor with USDOT funding, and cutting back on unprofitable passenger service.

Edit: found some old color footage of the M-497 being towed back by a GP7 or GP9 and of it operating

After the RDC, Budd tried to build a successor called the SPV-2000 in '78. The SPV stood for Special-Purpose Vehicle, but the running joke was that it really meant Seldom-Propelled Vehicle. The SPV-2000 was as big a failure as the RDC was a success. Budd took the brand new Amfleet passenger cars and converted them to a self-propelled Diesel Multiple Unit with a single GM diesel powering only one truck on each car. They had grand visions of these running in sets of 6 cars at 120mph, but mechanical troubles plagued them, leading to some operators to depower them and remove the controls and just operate them as a traditional coach hauled behind a locomotive (They were an Amfleet, after all). In the end, Budd only sold 31 of them, with 14 incomplete shells sitting around for decades (I believe those incomplete sets were still in existence into the 2010s).

Part of their problem was that, unlike the RDC, they only transmitted power to a single truck. This was part of Budd trying to get them below 45 tons in weight. FRA mandates that any locomotive over 45 tons requires a "fireman" aboard, while any locomotive below 45 tons can be operated by a single person. This is why the GE 44-ton switcher was such a hit with railroads, because they could cut down on yard crews by only having one-man crews. The problem with Budd's method of cutting down on weight was that now it had half the traction, so in wet or snowy conditions, they had a hard time getting moving.

The other big issue with the SPV was Budd decided to put a open brush generator head on the Auxiliary Power Unit generator, as well as using electric fuel pumps for all three engines, including the main diesel propulsion engine. So if you were operating them in rain or snow or there were wet leaves, they could (and would) short out the APU generator. If the engineer didn't quickly notice the APU fault light and shut it down, they would be running the lights and HVAC and fuel pumps off the small pack of NiCad batteries. So then it would deplete the batteries and the whole thing would grind to a halt. Oh, and now there is no power for the radio either. So one poor bastard has to now hike back to the nearest tower or trackside phone box and call in to dispatch to get a locomotive sent to pick them up. And he's the lucky guy. The other staff has to stay aboard a train in the dark/cold/heat with no lights/heat/air conditioning and try to explain to a bunch of angry passengers that they are going to be late getting to work or getting home. At least if they had put a mechanical fuel pump on the main engine, even after you lost all electrical power, you could still limp it in on the main engine, even if you didn't have interior lights and HVAC.

There were also other maintenance issues, mainly Budd making things hard to work on, largely because they were trying to cram a bunch of propulsion and head-end power gear in a car design that was supposed to be towed and have power provided to it by a locomotive. Metro North had an average of 9 days between failure, which is just sad. It was almost like Budd forgot everything they knew with the RDC. In the end, the SPV-2000 single-handedly killed the DMU market, which is a pity, because they are great for commuter operations, with most commuter lines still running locomotive-passenger car-cab car push/pull operations now.

The Budd Metroliner actually led to the development of the Amfleet, which lead to the SPV-2000. And the Metroliner grew from a US DOT experiment on a Budd Silverliner, which was an electric-converted long-range RDC prototype called the Pioneer III. Yeah, how's that for a circuitous path.

The Metroliner came from the 1965 High Speed Ground Transportation Act, which the US DOT enacted to try and build high speed rail to rival the Japanese Shinkansen, in hopes of reviving the rapidly-imploding passenger train market. The result was an Electric Multiple Unit with a semi-streamlined end with a stainless steel body that packed either 1200hp (Westinghouse coach cars) or 1020hp (GE parlor and dining cars) that were the heaviest EMUs ever built (165,000lbs) as well as some of the most powerful. The Silverliner IIs for example were 105,000lbs lighter but packed only 550hp per car. The idea was to let them rip down PRR's electrified 4-track Northeast Corridor. This was actually an early argument, as the US DOT wanted 150-160mph, while the PRR felt only felt comfortable with 125mph. In testing in 1967, the Metroliners would actually hit 164mph, literally ripping the windows out of some old 1930s MP54 EMUs headed the opposite direction on a neighboring track. That's flying, especially for a stainless steel brick. But due to the infrastructure and signal capabilities, the FRA would only allow them to operate at 120mph, which still made them the fastest passenger service in the US.

Although they were supposed to enter operation in '67, troubles with the propulsion and controls on the first-delivered Westinghouse car cutting out at 70mph delayed the launch until the beginning of '68. The GE-powered cars, despite later arrival on the property, entered service in PRR colors, even with the Penn Central merger just 2 months down the road but even then had issues with tripping circuit breakers and causing catenary outages on the aging infrastructure if more than 6 car train lengths were used. The Westinghouse cars wouldn't make their appearance until 1970, with PC getting in a pissing match with Budd and refusing to accept the additional 12 Westinghouse-powered cars. The Westinghouse cars, despite their greater power, had a slower acceleration rate than the old Silverliner IIs, which had half the horsepower, and they were prone to overheating when making numerous close stops and starts, as difficulty climbing out out Suburban Station in Philly and an inferior pantograph design that was prone to arcing. Additionally, the Metroliners weren't compatible with several station platforms, requiring either a redesign of the cars or stations. And all of them, GE or Westinghouse, had issues with packed snow shorting out traction motors and snow collecting under the cars on the dynamic brake grids and other electrical components and causing them to overheat. So frequently in the winter, they were instead towed behind GG1s and used as conventional passenger cars. The poor reliability caused anywhere from 25% to 40% of the fleet to be out of service at any one time.

Frustrations with the Metroliners mounted, and Penn Central, the US DOT and state governments poured money into R&D with Budd, GE and Westinghouse to try and get the Metroliners whipped into shape. But by '71, the FRA had knocked back the speed ratings even further, to just 100mph. This put them on the same footing as 1930s-vintage GG1s, which were a whole lot less trouble as well. With Amtrak's formation, the Metroliners passed into their hands (technically Penn Central, and later Conrail, still owned them and Amtrak leased them), who almost threw their hands up and just began using them as regular coaches until they realized they were the newest equipment on the roster. Instead Amtrak began a limited rebuild program that moved most of the sensitive electrical equipment to the roof to prevent the snow pack issue. The rebuild improved reliability and operation and allowed them to now be operated at 130mph, but it cost $500k per car, when they had cost $450k per car to purchase, and took a lengthy amount of time to perform.

In '73, Amtrak placed the order for the first of 600 Amfleet coaches. These took the aerodynamic bodies of Metroliners, but without any sort of propulsion, and became the bulk of Amtrak's car fleet. These are still in widespread use today. Budd would also use the Amfleet as the basis for the diesel SPV-2000 but they were even more trouble and Amtrak never purchased any. By '75, Amtrak was starting to repair the unmodified Metroliners, which now had 11 million miles on them and were becoming heavily unreliable but few were actually repaired. The amount of Metroliner trains per day sank, and even those trains being run were using less cars than demand warranted.

By 1976, Amtrak was looking to purchase new electric locomotives. The GG1s were still relatively reliable but they were pushing 40 years old. The E60 had been supposed to replace the GG1, but then had developed incurable instability issues that limited them to 85mph. So Amtrak began testing a Swedish-built electric called the AW1Rc4 that EMD was going to contract out to build. A single AW1Rc4 with Amfleet cars took over a Metroliner trip and matched it on time, a first, and the writing was on the walls, as Amtrak placed an order for the new EMD AEM-7s, as they would be called.

Amtrak's order for 118 Metroliner IIs suddenly got halved, and then cancelled altogether. Metroliner on-time performance had sank from 81% to 46% and Amtrak had began a rebuild program that was supposed to include all cars, but now was cut back to only 16 cars. To add insult to injury, 8 GG1s were regeared to 110mph and took over for Metroliners, hauling Amfleet cars, to make do until the AEM-7s began to arrive. The operation was changed from Metroliner to Metroliner Service to reflect the mixed equipment.

The rebuild program did eventually grow to 37 cars, as the AEM-7 construction took longer than expected. But in 1981, the AEM-7, known as the flying toaster or the Swedish meatball, began to show up and run 125mph service down the Northeast Corridor, beating Metroliners in every metric as well as starting to send GG1s and E60s into retirement (ironically, the newer E60s were gone before the GG1s they were supposed to replace) the Metroliners were soon shuffled off to the slower Harrisburg Corridor to run Keystone Service and renamed Capitoliners. They also purchased them outright from Conrail at this point, terminating the lease in '85. But reliability had slipped to the point where the AEM-7s now took over Keystone Service and the Capitoliners were just used as regular coaches. By '85, the Metroliner/Capitoliners were parked

The Metroliners did get a revival in the late 1980s, when Amtrak need cab cars for push-pull operations and realized they had a number of mothballed Metroliners with bad propulsion systems but good bodies and suspension. Now, instead of needing to turn the trains on wyes or use a locomotive on each end, the Metroliner cab cars at the end of the train could be used as a remote control stand and run the train in reverse. 29 Metroliners were converted and some are still in service today, although Amtrak has put forth a Request For Proposals to replace all the Amfleet and Metroliner equipment. When that RFP is filled, the Metroliner's will meet their end, which means the end of the US's first true high speed rail service, albeit one plagued with issues that never lived up to its potential and promise.

Those AEM-7s were some serious hot rods. Consider that the the old GG1s weighed 193.5 tons and were 79.5 feet long with 4620hp, and the GE E60 was 237.5 tons and 71 feet long with 6000hp. The AEM-7 tipped the scales at 101 tons, were 51 feet long and packed 7000hp. Yeah, 50% lighter, 20 feet shorter and 1000-3000 horsepower more. Its no wonder these things were serious speed demons. One member of the press stated "stated that no new locomotive since the New York Central Hudson had such an impact on speeds and schedule performance."

This photo captures just how much smaller the AEM-7 was compared to the huge E60.

Amtrak actually tested two locomotives at the same time, settling on the AEM-7. Both were European, the AEM-7 being a Swedish-built ASEA Rc4. The other was a French CC21000. These were bigger than the AEM-7 but smaller than the E60 and the GG1, and packed 7900hp. But Amtrak wasn't fond of how they rode, and the rougher conditions of the Northeast Corridor caused suspension issues. I think the CC21000 is pretty odd looking, almost reminds me of those Japanese dekotora trucks.

Why did Amtrak turn to Europe? Well, for starters, no US manufacturer had an electric passenger locomotive in their product lineup. So while it would be an estimated 3 year turnaround to get a Eurpoean locomotive imported to the US, it would take longer for an American manufacturer to design, test and then produce an all-new engine. And Amtrak needed equipment now. The other reason, and this is a bit of speculation, may be that Amtrak didn't have faith in an American manufacturer at that moment. They had had a slew of equipment built by EMD and GE that had been plagued with issues, largely because, rather than offer unique passenger offereings, EMD and GE were taking freight locomotives and slap-dash converting them to passenger usage. The EMD SDP40F had derailment troubles that resulted in many railroads banning it from their tracks, the GE P30CH had also suffered from reliability troubles and the same oscillation issues that the U28CG and U30CG had had, the GE E60CH failed to replace the GG1s because it had yaw troubles that restricted it to 85mph, the Budd/GE/Westinghouse Metroliners never lived up to their full potential. It may be that Amtrak just felt that a European manufacturer, who had been doing long-haul passenger electrics for a while now, might have better luck.

You'll need to log in to post.