I'm just glad to see passenger service in this day and age.

GM&O #1900, an incredibly unusual (and unattractive) beastie. Built by Ingalls Shipbuilding as a Model 4-S, this was Ingalls' attempt to get into the railroad market, in a similar manner to how Fairbanks-Morse tried to jump from naval building to locomotive sales. The 4-S was supposed to be the largest of 5 models that Ingalls would produce. Instead, they made a single 4-S and never sold another locomotive. Despite testing on the Louisville & Nashville, Southern and Seaboard Air Line, none of them bit.

The 4-S was actually well-liked by crews. The turreted cab gave it excellent visibility compared to EMD F-units and Alco FAs. It had windows in the rear, plus an internal compartment to stand in, so brakeman could ride back there and help with switching manuevers instead of hanging off the side. The converted marine Superior Engines & Compressors V8 diesel engine made 1650hp, which was comparative to offerings from EMD, Alco, Baldwin and Fairbanks-Morse at the time. It came with multiple unit connections that were compatible with other units and Ingalls offered the option of a steam generator for passenger use (#1900 was not optioned with one though) And GM&O crews said it was incredibly rugged and tough. Some higher up at the GM&O had a soft spot for the orphan engine, because it was kept in service for 17 years, and was even rerailed and repaired after a derailment dumped it on its side.

So why didn't the Ingalls 4-S sell better? Perhaps a market that was already too crowded? Railroads were nervous about the converted marine engine? Turned off by it's appearances? Hard to say. When GM&O retired it in 1966, they offered it to the Illinois Railroad Museum for $3000, about scrap price at the time. The IRM had just moved to their current-day site and was strapped for cash at the time, plus they were more focused on electric interurban cars, trolleys and freight and passenger motors at the time. So the only Ingalls 4-S was cut up.

In reply to Pete Gossett (Forum Supporter) :

Yeah, cosmetically the carbody is a mess. But functionally, it was really much better than anything anyone else was offering at the time. It was exactly what crews wanted at the time: better rearward visibility and a place for the front brakeman to safely work.

Doing some research, some people say that railroads didn't buy into Ingalls because they were unsure of the converted marine engine. I'm not sure I buy that though, because Fairbanks-Morse sold plenty of locomotives using their converted marine engine. And if anything, the Fairbanks-Morse vertically-opposed two-stroke engine was much more exotic than the Superior V8.

A short history of the Pomeroy & Newark Rail Road. Part of this has been repurposed into trails, and part still operates as the Wilmington & Western excursion line, which I have mentioned before.

I believe one of the steam engines parked at that railroad-themed restaurant I designed was from the P&N.

The Ingalls 4-S reminds me of the GE BQ23-7, nicknamed "Buses" or "Aegis Cruisers". It was a regular B23-7 but with a massive cab (Q for Quarters) so the whole crew could ride up front, eliminating cabooses. SCL/Family Lines was the only buyer and they were all scrapped in the CSX era.

Headed into 1970, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe had a whole lot of EMD F7s. I think it was something like ~230 A-units and ~215 B-units. The problem was, the F7 was getting old, with the first units manufactured in 1949 and production wrapping up in 1953. Santa Fe considered replacing them with new road switchers from EMD, but the price of a new locomotive at the time was $150,000. Replacing 230+ locomotives at $150k a pop was going to be a huge chunk of change. They could rebuild and overhaul their F7s and save money, but the streamlined carbody made them a hassle doing any yard work or switching with, with the engineer having to hang his head out the window and brakemen hang on the ladders off the sides.

So Santa Fe decided that they were going to take their F7 A-units, slice the carbody off and then install a road switcher body on top, while overhauling everything inside, all for $60k a locomotive. They actually approached both EMD and GE about contracting the conversion process out to them and both manufacturers basically said "It can't be done." The concern was that the F7 was not just a body plopped on a frame like a road switcher GP7, but instead the body was used for structural integrity. Both GE and EMD felt that if you chopped the body off and just stuck a new body on, you would end up with a locomotive that would sag in the middle and develop all sorts of structural concerns as time went on. And if you went an engineered a new frame, that would end up costing more money and make the rebuilding program less of a savings.

ATSF remained convinced it could be done, and decided to do the conversions themselves at their Cleburne, Texas shops, although engine, traction motor and generator overhaul would be done by the San Bernadino shops. The program was named CF7 for Converted F7. Not exactly the most creative name, but it got the point across. And they would start by building a single locomotive to determine if it would be cost effective and if it would work before comitting the whole fleet. The locomotive chosen to be Patient Zero was Santa Fe #262C (The C designated that this was delivered as a three-unit A-B-A set and was the third unit) and would become CF7 #2649.

The #2649 would end up taking the longest amount of time to convert, at just over a year, but that was to be expected, being the first in a major undertaking. #2649 also ended up being unique amongst the CF7s. First, it had dynamic brakes, which no other CF7 would have. This was accomplished by using the long hood from a retired GP7B (a cabless GP7) and it's dynamic braking grids, chopped to fit the proportions of the F7 frame. This also means it was the only CF7 to use an existing hood, instead of one fabricated at Cleburne. Also the steps on the ends were smaller than the rest of the CF7s. After going into service, crews complained the steps were easy to miss, and Santa Fe responded by making the steps wider and lower on the rest of the class. The #2649 also received additional reinforcement to the 1/2" floor plate in the form of a 1.5" floor plate along with the 24" side sill that they added, but after being put into service, they realized that the 1/2" floor plate with the side sills was strong enough and none of the other CF7s received the thicker floor plate. And finally, #2649 used an unchanged 567B powerplant, while others would receive the hybrid 567BC engine.

Once #2649 was completed, coming in at actually less than the projected $60,000 cost, Santa Fe fully committed to the CF7 program and every last F7 that they still owned was sent to Cleburne. The body was cut off, the 24" tall side sill was welded on to beef the frame. The 567B engine was removed and sent to San Bernadino where it was rebuilt and had the cylinder liners replaced with the improved 567C style, to create a 567BC, still rated at 1500hp. Santa Fe looked at a 645 swap (#2452 actually received a 2000hp 645) or even just putting 645 power packs on the 567 bottom end but decided it was too costly, plus they already had a huge supply of 567 parts and these locomotives would be do switching, light work or branch duty and didn't need to be horsepower monsters. The trucks were removed and had their traction motors pulled out. Generators and traction motors went to San Berdoo as well, to be rewound, while the trucks were overhauled and refurbished by Cleburne. The electrical system was entirely rebuilt, with new wiring harnesses and switch gear and circuit breakers. A low (but taller than a regular EMD low) short hood and a tall long-hood were fabricated. The cabs on the early units also used the stock curved roof line of the F-unit, as a segment of the F7 roof was carved out and a cab built under it, to save money. But this cab was found to not save money because it had to have doors custom-made to fit the proportions of the cab, so later units used an all-new cab with an angled roof that could use standard cab doors, cutting the cost of the cab by 50%. The later cabs also had added insulation and a lead plate in the roof to cut down on NVH. All CF7s were also fitted with air-conditioning.

By the time the CF7 program hit its stride, Santa Fe was cranking one out, from initial inspection of the F7 donor to painting the CF7, in 45 days, pretty fast for such a thorough overhaul. The program also came in at $40,000 per locomotive, 33% less than what they originally planned for. After 8 years, every F7 still owned by Santa Fe was swapped over to a CF7. So the CF7 program could be called a smashing success. They found use in yards, light branch duty and hauling local freight, although they occasionally did mainline work. They were frequently paired up with old F7B units. Some were even configured for remote control.

By 1984 though, they were starting to head for 10-15 years old, and Santa Fe began selling them off to shortlines at $20k a piece. In 1987, the last CF7s left Santa Fe property. GE ended up with a bunch of them as trade-in material, but cut them up. Amtrak also ended up with some for yards and work trains. And quite a few of them went to leasing companies.

Today, their numbers have dwindled, but there are a few still out there working the rails, and one preserved in a museum. Sadly, #2649 did not survive, but was parted out a number of years ago and donated it's trucks to a restored Reading F7.

In reply to NickD :

Oh I forgot about those! I think they passed through our hometown a few times, or I at least knew about them as we were on the CSX/Seaboard System/L&N/C&EI mainline.

Two weeks before CoVid 19 hit town thieves stole the copper pipe and brass fittings ready to be mounted on the restoration of this 1904 Horden steam locomotive.

Santa Fe actually tried another rebuild program due to the success of the CF7. Santa Fe was a pretty faithful EMD customer, but they had dabbled with other brands in the form of switchers, and in the '70s, there were quite a few of these still scuttling around yards and ports. So Santa Fe decided to try and give them a CF7-style overhaul: they would yank the prime mover, body and electrical system and rebuild it. So, for the pilot locomotive, they grabbed a 1943-built Baldwin VO1000 switcher #2220 out of their fleet and sent it to Cleburne. The photo is of #2257, but #2220 would look identical.

They removed the regular Baldwin hood and installed a new hood that strongly resembled a GP7 long hood. The De La Vergne VO-8 1000hp 4-stroke naturally-aspirated inline-8 was replaced by a 1500hp EMD 567BC supercharged 2-stroke, requiring considerable fabrication to adapt to the VO1000's cast-steel frame. The electrical system and controls were completely replaced, as was the generator and traction motors, although it retained the Blomberg B trucks that were favored by Baldwin and Alco and it's original cab. Santa Fe called the result an SWBLW (Switcher Baldwin Locomotive Works) but to crews and railfans it was nicknamed "The Beep", a contraction of Baldwin and Geep. It was originally numbered #2450, although it would later be reunumbered to #1460.

Ending up several tons heavier than a GP7 and lower-geared, the Beep was loved by crews for being a real lugger. It had some serious tractive effort. They also preferred the smoother ride quality of the Blomberg Type B trucks over the AAR Type As that EMD used. But the program ended up way over budget, and the conversion cost far more than Santa Fe was prepared to spend. So, despite having a list of potential rebuilds that even included 2 Fairbanks-Morse H-10-44s, Santa Fe decided to scrap all the orphan units and replace them with new EMD SW series. But #1460 was already done and invested in, so Santa Fe kept it on the job at Port Terminal in Houston. Later on, in the '80s, it would receive air conditioning, and the backhead was modified to use standard EMD windows, instead of the Baldwin windows. EMD retired their last end cab switchers, of all brands, in 1987, but kept the Beep around. The odd little engine would last until 2008, at which point it was retired and parked at Topeka, before being donated to a museum in Barstow, where it remains on display.

The other big Santa Fe rebuild resulted in the weirdly nicknamed "Slushbuckets": The SD26.

AT&SF had been the largest purchaser of the EMD SD24, buying 80 of the 224 sold (Union Pacific was a close second with 30 SD24s and 45 SD24B cabless units). The SD24 was a 2400hp, 6-axle road switcher that EMD had built between 1958 and 1963, and was notable for a couple reason. First, the SD24 was the first factory-turbocharged EMD. Before this, they had all used Roots-blowers huffing into the 2-stroke GM diesels, but after seeing several railroads add turbochargers feeding into the Roots-blowers to boost horsepower, in particular the UP's "Omaha GP20s", EMD decided to follow suit. EMD completely removed the Roots blower though and installed what they called a "Turbo-Compressor." This was a turbocharger that was attached the the front engine geardrive and had an overrunning clutch, so that at low RPMs before there was enough exhaust to spool it, it operated as a centrifugal supercharger, and then once exhaust temperatures built up, the Turbo-Compressor would freewheel on the overrunning clutch and act as a turbocharger. Pretty slick.

Also notable was that this was the first high-powered EMD road switcher. EMD had typically lagged behind Alco and Fairbanks-Morse offerings in terms of horsepower, making up their sales in reliability, ease of maintenance, customer support and affordability. But the SD24, with it's 2400hp 567D3 engine now offered horspower on the level of Alco and Fairbanks-Morse, while still retaining that EMD reliability and ease of maintenance. And, thanks to the turbocharger, that power was available at all altitudes, so railroads that operated at serious elevations were big fans of them.

Cosmetically, the big identifiers on an SD24 are the 4 "torpedo tube" air reservoirs on the roof, just behind the cab. An SD24 could be optioned with either a high nose or a low nose. The factory low nose had a downward slant to it. Many high nose units had the nose chopped down, and typically the homebuilt conversions had a hood that was flat across the top. Santa Fe bought their SD24s with low noses, while UP and CB&Q, for example purchased high nose units.

The SD24, while not a huge sales success, was a good locomotive and well-liked by railroads that purchased it. But, by 1973, they were starting to develop issues. Not with the engines, but with the electrical systems. These were built before the Dash-2 solid-state electronic systems were invented by EMD, and they used essentially the same electrical system as the GP7s. But with six 400hp traction motors, they put a lot of strain on the generator and wiring. Burnt up wiring, tripped circuit breakers and other gremlins began to crop up as they entered their second decade of service.

So, with the CF7 program plugging along nicely, Santa Fe decided to give their SD24s a big overhaul. Unlike the CF7 and The Beep, the SD24 rebuild program was performed directly at the San Bernadino shops, instead of at Cleburne with components shipped to San Berdoo. The 567D3 was torn down, overhauled and rebuilt with 645 pistons, liners and heads, which bumped displacement and made for a more efficient engine. This bumped horsepower from 2400hp to 2625hp. The wiring system was completely redone with new wiring harnesses and Dash-2 computerized circuit cards. The bell was moved from the front pilot and mounted on the roof between the dynamic braking fans and radiator fans. The footboards were redesigned. Air-conditioning was retrofitted. Improved dynamic braking grids were installed to allow longer operation.

The biggest cosmetic change was they added a new air filtering system directly behind the cab, which gave them an odd hunchbacked appearance. Because that was where the air reservoirs were originally mounted, those instead had to be relocated. Two were moved to the tops of the dynamic braking grids in the middle of the long hood, flanking the dynamic braking cooling fan. The other two were mounted on either side of the radiator fan at the very rear of the locomotive. And although they originally kept the single-piece windshields from the SD24, they were later retrofitted with the newer EMD 2-piece windshields to cut down on inventory and save cost.

The SD26 were nicknamed "Slushbuckets" by rail fans and crews for their mushy exhaust note and subdued turbocharger whistle. Santa Fe put the SD26 into service on mainline intermodal freight on the Kansas City -La Junta - Albuquerque - El Paso freight pool, while others ran general merchandise up and down the Coast Line. By 1985, the SD26 was becoming outdated, and Santa Fe retired them all. They sold 35 of them to the northeastern Guilford Lines, and the other 49 of them (1 had been wrecked and scrapped in '74) went to EMD to be traded in on 15 new GP50s. In 2012, the last SD26 was finally scrapped.

In reply to NickD :

On a locomotive like the SD24 what are the reasons to want a tall hood vs. the short one?

In reply to Pete Gossett (Forum Supporter) :

Short hood was preferred, and basically became the standard, because it had much better visibility. Tall hoods were required on the early road switchers if you ordered a steam generator, as that was where the put it on the smaller units. Later bigger road switchers tucked it in the long hood. Plus there was a comfort factor, as the bathroom was up in the front hood, so a tall hood gave the crew more room to use the head, while a short hood resulted in cramped quarters. Also, many railroads said there was a safety factor to the tall hood, it was more metal between the crew and the front of the engine if they hit something. Some railroads (B&O) even preferred to run road switchers long hood-first for collision safety.

EMD didn't offer a short hood until the GP18. Alco didn't offer one until the Alco RS27. GE largely made short hoods and then custom-built high hoods for railroads that requested them. Baldwin never offered a short hood, and neither did Fairbanks-Morse.

The railroads that preferred tall hoods were Norfolk & Western and Southern (and as a result Norfolk Southern), and to a lesser degree, CB&Q. They kept buying tall hood units long after the short hood became standard and everyone else abandoned them.

Southern had some high hood GP30s that they passed on to Norfolk Southern that I thought were absolutely gruesome looking. The regular low hood GP30 was a great looking engine.

No.

Yes.

In reply to NickD :

Interesting. With that much weight behind you I can't imagine another ~4' of steel would add any real safety in a head-on collision. Especially when compared to the added visibility the short hood provides.

Saw this old girl hauling butt down some local track this morning. She could really use a repaint, but now we know what we're going to eventually add as our "switch engine" on the model railroad!

.jpg)

I was on my way to grab a Little Caesar's pizza for lunch, heard a horn and whipped down a side street to catch Mohawk, Adirondack & Northern's little ex-Air Force GE switcher running down the street with 5 covered hopper cars. I was a little disappointed it wasn't one of their big Alcos, but GE 80-tonners aren't exactly a dime a dozen these days either.

Proof that "There's a prototype for everything" is true: That is a Canadian Pacific "Jubilee" streamlined 4-4-4 (one of only five!) at Galt towing a steel underframe wooden-bodied baggage car, a Budd RDC and a steel lightweight passenger car on a commuter run in February of 1954. Clearly CPR missed the note in the RDC owner's manual where towing an RDC or towing with an RDC would void the warranty.

Those CP 4-4-4s were odd birds. They were really the only railroad to buy 4-4-4s en masse. Philadelphia & Reading bought a few, didn't like them, and had them converted to Atlantics. CP bought two classes of them, one before WWII and the other after, and they were real fliers.

The early F2a class engines (3001-3004 number series) had 80" drivers and clocked 112mph, a record for a Canadian steam engine. But they had limited pulling power, between the tall drivers and only 4 powered axles. And the main rods, which drove the lead axle and then had connecting rods running to the rear axle, had a tendency to bend when the locomotive was reversing.

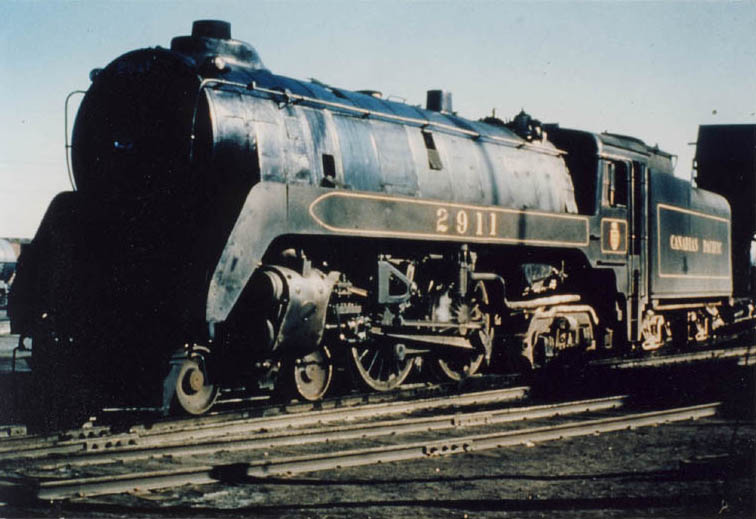

Then, after WWII, they bought the F1a 4-4-4s (2910-2929 number series), which had a shorter 75" driver to get a bit more pulling power and acceleration out of them. They also ran the main rod to the rear driver and the connecting rod forward to the lead axle. This solved the bending issue but caused some oscillation at higher speeds. They also had a less streamlined pilot, with a conventional beam and then a steel pilot with a drop coupler. They still weren't particularly powerful though, especially not when compared to the fleet of Pacifics and Hudsons that CP already owned. Also, while all of the others were painted the conventional CP light blue and maroon, the #2911 wore the gold and black freight colors.

The F1as did rate the occasional light freight duty (emphasis on "light") thanks to being small with low axle loadings. Like working this spur on a pier.

You'll need to log in to post.