Ever see a locomotive on jackstands?

In reply to NickD :

Doubtful. They're pretty stout. They have a truck pulled out from under it and it looks like they are servicing the traction motor(s).

ShawnG said:Getting under it would give me the heebie jeebies no matter how strong the stand.

The good thing is, they really aren't working under it much while it's in the air. You get under it and disconnect all the connections to the truck, then jack it up and pull/roll the truck out from under it, do all the work to the truck away from the locomotive, then roll the truck back under it, lower the locomotive down onto it and then hook everything back up.

NickD said:ShawnG said:Getting under it would give me the heebie jeebies no matter how strong the stand.

The good thing is, they really aren't working under it much while it's in the air. You get under it and disconnect all the connections to the truck, then jack it up and pull/roll the truck out from under it, do all the work to the truck away from the locomotive, then roll the truck back under it, lower the locomotive down onto it and then hook everything back up.

If you look closely, you'll see they have the loco on stands and have blocked the front end with a concrete barrier, and the truck is out in front of that.

I'd be much more nervous about being involved in the repairs on a steam locomotive when they are in the air. Could you imagine being the guy who has to crawl under a Y6 and line up the drawbar pin between the front and rear engine? There was a great story by David Page Morgan where they swung by the Roanoke shops and a crew was rewheeling a Y6 and was splitting the engine in half and a crew member said that sometimes the drawbar pin would fall right out. Then he point at the engine they were splitting and said "We've been trying to get that one out for a day and a half."

Pennsylvania Railroad #460 aka The Lindbergh Engine. Built in 1914 as the last of the PRR's 80 homebuilt E6s Atlantics, the #460 and her sisters were all 80" drivered, superheated, equipped with Belpaire boilers and were quite powerful for an Atlantic (they were the first US engine to have 1000hp per drive axle). They were only beat out in size, power and speed by the Milwaukee Road's Class A streamlined Atlantics. When introduced, the E6s held down the top spots on PRR passenger trains, although the arrival of the even more powerful K4s Pacific bumped them down rather quickly. Still, the E6s handled most of the short-haul passenger trains and commuter operations, right up until retirement.

Having lived a rather uneventful career, in 1927, #460 gained her moment of fame. When Charles Lindbergh returned to the US by boat after his transoceanic flight, there was a reception in Washington D.C. where he met Calvin Coolidge and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. All the news companies engaged in an outright race to get the film of the reception to New York City first to see who could break the story. While all the other news companies had chartered airplanes to transport their footage, International Newsreel Company placed their bet on the railroad. And the Pennsylvania Railroad was their (iron) horse. The PRR had a direct route from D.C to NYC, it was quadruple-tracked the whole way so that there was no risk of the train getting caught up in traffic and the PRR had fast, powerful engines (an earlier E2 Atlantic had set an unofficial and somewhat dubious speed record of 127mph a few years before) and they had track pans where steam engines could fill up water on the fly and reduce time spent stopped for rewatering.

PRR management, always hungry for publicity, hand-selected the #460 and her crew. While a K4s was more powerful, since the locomotive would be hauling a single baggage car and a single passenger car, an E6s had sufficient power. And theoretically, thanks to less rotating and reciprocating mass, an E6s had higher top speed and could safely maintain high speeds for long periods of time without connecting rod or valve gear failure. They also made sure that the route was going to be cleared for the #460 and her short train.

After the award ceremony wrapped up, the footage was immediately rushed to the waiting #460 and the locomotive, two cars and film crew set off for New York City on a white knuckle ride. The train left D.C. at 1:14pm and arrived at Manhattan just 2 hours 56 minutes later. Over the 225 mile trip, average speed was 82.7mph, with a top speed of 115mph. That average also included a 3 minute watering stop, after the water scoop failed and they were unable to rewater on the fly, as well as uncoupling the #460 and hooking up a DD1 jackshaft electric to haul the final leg into Manhattan.

During the trip, the competing company's airplane was spotted flying overhead and waggling its wings at the train as a taunt. And while the airplane would actually end up beating the #460 to Manhattan, it was the train-carried footage that made it to theaters first. Why? The baggage car behind #460 was set up as an impromptu darkroom, so that during the trip, they were developing all the film and it could be immediately rushed to theaters on arrival. The airplane-carried footage had to be driven from the airfield to a studio, developed, and then driven to a theater, meaning the footage itself arrived at the theaters hours late. Lindbergh was never asked his opinion on the fact that a steam locomotive showed up an airplane delivering footage of his return from his transoceanic flight, but I'm sure he was not amused.

After that trip, the #460 faded back into obscurity. Her career was spent mostly hauling commuter runs on both the PRR subsidiary Long Island Railroad, as well as hauling trains on the joint PRR/Reading-operated Pennsylvania-Read Seashore Line. In 1951, as the PRR was starting to dieselize and they began scrapping E6ss. The #460, at this point in time, received an overhaul using parts cannibalized from other retired E6ss. The drivers on the engineer's side are from PRR #1565, the air reservoir on the fireman's side was from PRR #690 and the reservoir on the engineer's side was from PRR #782. In 1952, her tender was replaced with the tender off of #1565 as well, while the #460s tender was converted for MoW use. During a 2010 cosmetic restoration, many other parts were found to have been swapped at some point, with over 23 different locomotive serial numbers present on the #460. During the final days of operation, #460 hauled a number of railfan specials, then was operated on the PRSL from 1953 to 1955 before being retired.

The PRR, always historically minded, set the #460 aside, moving it to their Northumberland heritage collection, before donating it to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in Strasburg, PA in 1969. There the engine sat on display outside for many years, slowly deteriorating.

Finally, in 2010, the #460 was given a 6 year cosmetic restoration and moved inside of the new display hall.

I've seen her in person and she looks like a brand-new engine.

An audio recording of the #460 hauling a commuter train in '54 while working for Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines. The engineer is certainly not sparing any throttle. The whistle is sounding pretty worn out by this point. It should be a PRR 3-chime but it sounds like only one tone is really working

The other famous PRR Atlantic is PRR #7002. #7002 was an earlier E2 light Atlantic (the E6 was a heavy Atlantic) that was built in 1902. While the E2 used the same 80" drivers of an E6s, it was not superheated, weighed 70,000lbs less and had smaller cylinders. They were still thoroughbred fliers though. On June of 1905, the PRR was running the first westbound run of the Pennsylvania Limited (which would be renamed to the Broadway Limited in 1912) which had previously only been eastbound. At Crestline, Ohio, the #7002 was coupled on as a replacement engine. Delays near Mansfield, Ohio would result in the train leaving Crestline, Ohio twenty-five minutes late. Not wanting the inaugural trip to be late, and with the rules and regulations being a bit more lax at the time, the crew really opened the #7002 to make up time.

The next bit is a bit controversial. Near Elida, Ohio, the #7002 and her train was reported to have covered 3 miles in 85 seconds, and was clocked at 127.1mph. This would make the #7002 the fastest steam locomotive. The issue is that it was not an official record attempt. Also, this speed was calculated by two separate observers at Elida and AY Tower. It is very difficult to calculate time and speed just by the signal registers. Also the average speed from Elida to Fort Wayne (the train's final stop) was only 68mph. So, it may be possible that it went that fast, but very dubious. After all, #460 was a larger and more powerful engine towing only 2 cars, not a fully loaded passenger train, and only hit 115mph. PRR, always the glory hound, always boasted of that record. Despite that, the #7002 faded into obscurity. In 1916, it was rebuilt into an E7a, which was PRR's upgrade program for the aging E2a/b/cs. The most important upgrades were switching to piston valves for the valve gear in place of the old slide valves, and increasing piston diameter from 20.5" to 22.5".

In 1939, while preparing for the 1939 New York World's Fair, the PRR decided they wanted to clean up and display the #7002. Management did some digging to find what division she was operating in to bring it into the shop and was startled to discover that in 1935, when the PRR retired some of the old light Atlantics due to the arrival of K4s, the #7002 had been scrapped. So, they grabbed #8063, also a 1902-built E2 that had been rebuilt to an E7, and backdated its appearance to the as-built E2 appearance, as well as renumbering it to the #7002. For this reason, while there seem to be tons of photos of #7002, they are almost all entirely of #8063. I was unable to find any photos of the true #7002, actually.

The #7002 would be largely retired and set aside by the PRR. They would drag it back out to the 1948 Chicago Railroad fair, and then after that it was sent to Northumberland, PA to be part of their heritage fleet. It would occasionally be moved to other events to be displayed.

Stored at Northumberland, with B6sb 0-6-0 #1670

After the Penn Central merger in 1968, the entire collection was donated to the Railroad Museum of PA in Strasburg in 1969. Unlike the #460, the #7002 saw a second life. Since 1965, Strasburg Railroad had been leasing and operating D16sb 4-4-0 #1223 from the PRR. In 1982, while their Canadian National Mogul #89 was undergoing an extensive overhaul, Strasburg leased the #7002 from the RRMoPA and put her back into service hauling trains.

From 1982 to 1989, the #1223 and #7002 traveled the rails. They operated together, even doing occasional doubleheaders, on the Strasburg's 4.5 mile line. And together, the two engines also made numerous trips over old PRR trackage. In the summer of '85 they went to Harrisburg, and then in the summer of '86 they doubleheaded to Philadelphia. They also made a doubleheaded excursion from Hanover Junction and Gettysburg on November 19, 1988 to celebrate the 125th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's trip over the same route to make the Gettysburg Address.

In 1989, Strasburg ultrasound-tested the firebox of both #1223 and #7002 and found that the firebox walls of both engines were too thin to continue operating. The Railroad Museum of PA decided that they did not want the fireboxes replaced, as that would be replacing the original historical fabric and both engines were retired from service and moved back over across the street and put on display. This was the last time that a PRR mainline steam engine would operate, and also the only time that PRR steam would doublehead in the preservation era. Neither of those look likely to happen anytime soon either.

An old video of #7002 and #1223 doing the doubleheader trip to Harrisburg. Whoever was firing the #7002 was doing a pretty poor job. Awful lot of black smoke.

So as I said, not likely to see PRR mainline steam engines anytime soon. Most preserved PRR engines ended up at the Railroad Museum of PA, who has made it clear in recent years that they will be beautifully cosmetically restored, moved indoors and taken care of but not operated. So, barring a major change of heart (unlikely) all those engines are off limits. So, that is 13 out of the 22 preserved PRR steam engines.

Of the other 9: one is an old B4a 0-6-0 , #643, at Dillsburg, PA that is the only operational PRR steam engine. Another is a B6sa 0-6-0, #60, which is privately owned and has sat inoperational at the Wilmington & Western for years. Another is #35 Reuben James, an ancient 1860s 0-10-0 at the Children's Museum in Indianapolis, unlikely to ever run again due to its age and configuration. The Smithsonian has the 1831 2-4-0 John Bull, which was operated briefly in 1981 for its 150th birthday but will never see steam again and is realistically pretty useless. There is an odd narrow-gauge Mogul from PRR subsidiary Waynesburg & Washington in Waynesburg, PA. The Western NY Railway Historical Society has the only remaining Pennsy I1sa 2-10-0 in Hamburg, NY but she is too big, heavy and slow to ever be a tourist engine. And then there is PRR #1361, one of 2 preserved K4ss, in Altoona which operated very briefly in the '80s and has been undergoing a tumultuous on-again-off-again restoration for the past 30 years. Going over to PRR subsidiary Long Island Railroad, there are two G5s Ten-Wheelers, #35 at Oyster Bay and #39 at Strasburg.

So, what PRR mainline engines (not switchers) are we likely to ever see operate:

LIRR #35 is owned by the Oyster Bay Railroad Museum. Supposedly they are chipping away at restoring her, but the plans and details are very vague and from what I can read I don't think they have any track, just a turntable and an old station. I'm really confused by this one, since it sounds like they are restoring her to operation, unless they have a deal hammered out with the Long Island Railroad to run it over their tracks. I don't know. Of the 4 options, this one sounds least likely.

LIRR #39: Back in the early '90s, after losing PRR #1223 and #7002, Strasburg was in talks to acquire LIRR #35 or #39, since they wanted a PRR engine. Neither worked out, and Strasburg instead ended up with Norfolk & Western #475. But a few years back, Strasburg hammered out a deal with the LIRM: LIRM raises $1 million dollars in 15 years and Strasburg will restore and operate it under a 49 year lease. If the money can be raised, Strasburg will get it done. But, money-raising is difficult and Long Island is also pitching a fit about losing the engine to Pennsylvania for 50 years. The LIRM has said, they have no facilities to store the #39 indoors so they would have to construct those, they have no operational turntable so they would have to sink $3 million to restore the one at Greenport or $7 million to rebuild and install one they got from Buffalo, and then would have to work out a deal with Long Island Railroad to run on their tracks, so in the long run its more viable to send it to PA. But, it wouldn't be the first time local politics interfered. I call this one a 50/50 shot, and it'll be a ways out before it's run

PRR #1361: One of two K4s Pacifics in preservation (the other is #3750 at RRMoPA), this one actually ran excursions in 1987, albeit very briefly. There were some issues with the guys doing the restoration and the guys operating her, and she was never quite right. Lots of hot bearings, a drive wheel losing its tire, a cracked axle and other gremlins like low-speed derailments plagued the few trips she made before being parked. It was supposed to be re-restored correctly but parts went missing, the boiler was found to be absolutely worn out and money troubles and backroom politics meant it spent years apart at Steamtown and Altoona with little getting done. The plan has changed a few times from operational restoration, to fixed display, to operational again. Its become a running joke/argument about when #1361 will be fired up. But, it has gained new financial backing, it's getting an all-new boiler, it's getting roller bearings (from an old Timken blueprint that PRR commisioned in the '30s!) and Positive Train Control compliancy. No clue on how close they are, but I've heard a lot of people say "#1361 is closer than people think", so hopefully she gets to navigate Horseshoe Curve again sometime in the near future.

PRR #5550: Instead of restoring an existing engine, these mad lads are building an all-new engine. And not just any engine, but a PRR T1 4-4-4-4, of which there are none preserved. The first reaction from people was that this was a pipe dream, but they are really cranking on her. They're casting the drive wheels, they've acquired a PRR long-haul tender to restore and use behind it, they're reverse engineering the unique Franklin rotary cam valve gear, they've fabricated the nose piece and cab, the new boiler is almost done. Supposedly they have agreements in place for places to operate it once its done, which is amazing because it is a large, heavy engine. The completion date is set as sometime in 2030. We'll see.

Begs the question.

Could we build a better, faster, stronger, safer steam locomotive with modern metallurgy and controls or have we forgotten a bunch of what we need to know?

ShawnG said:Begs the question.

Could we build a better, faster, stronger, safer steam locomotive with modern metallurgy and controls or have we forgotten a bunch of what we need to know?

I'd say it's the former, not the latter. A boiler is a boiler; they're still designed in largely the same way they were over a century ago. The knowledge of properly running the locomotive is out there as well, and with modern metallurgy and engineering programs that show you where the stresses will show up, it'll be safer as well. All in all, I'm pretty excited about it.

It's totally possible that this is my great grandfather in this picture.

I still remember when they brought this engine out after it's "restoration". We followed along in my grandfather's car and watched it go around horseshoe curve.

ddavidv said:Vice Grip Garage takes a tour of Trackmobiles and fires up a EMD SD-40.

I was around those on river boats and the chief always blew the cylinders down before starting no matter how long it was shut down. He skipped that. 1 leaky injector or a coolant leak and it's power pack time.

ShawnG said:Begs the question.

Could we build a better, faster, stronger, safer steam locomotive with modern metallurgy and controls or have we forgotten a bunch of what we need to know?

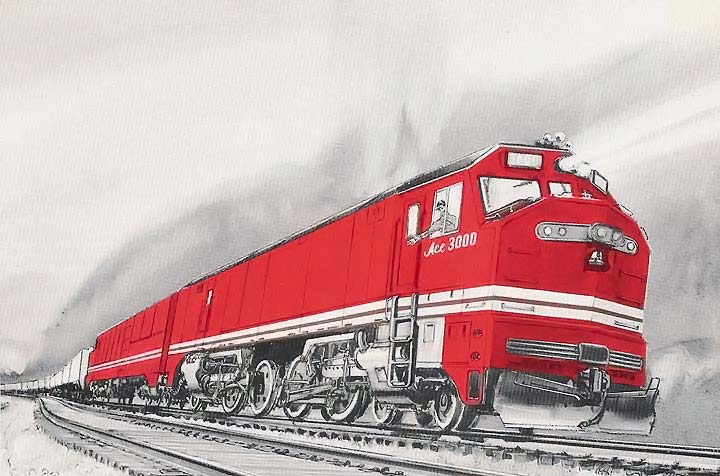

They actually tried it in the 1980s with the ACE3000. When fuel prices were high in the late '70s, Ross Rowland thought that since coal was a cheaper fuel source, they could build a modern coal-powered freight locomotive. He was also convinced that, as some of the early diesel-era testing showed, steam locomotives were more efficient and offered more horsepower per dollar. So he put together American Coal Enterprises with a bunch of like-minded individuals in the coal and railroad industries. They used his C&O Greenbriar #614 as a data acquisition point and did tons of testing up and down the Chessie Systems mainline. But then oil prices dropped, which killed off one large driving force behind the project, and backroom politics fully sank the program before a prototype was ever even built. To date, Rowland still swears by the data they recorded and that the program could be viable. He's supposed to be releasing an autobiography sometime that will go in-depth and I'm sure it will be quite a read. Rowland is kind of the railroading version of Smokey Yunick.

Building a new steam engine, there are a few hurdles. Finding places to make some of the big parts is a bit difficult. For example, the T1 Trust found that there are no longer any foundries large enough to cast the frame in one piece, so they are having to have the frame cast in multiple pieces and then weld them together. Strasburg has found an Amish-run foundry (the Amish are in the same boat, they run old equipment that you can't get parts for) that will cast drive wheels and other parts for them. You can't just caul up Westinghouse anymore and order a cross-compound air pump either. You have to make all of that. Even boilers: an industrial boiler is not the same as a railroad boiler. Texas State Railroad, trying to keep money in the state, had a Texas-based industrial boiler company build boilers for their operational steam locomotives. They installed one and put it into service and had yanked the boiler off their other engine to install the new one, and then discovered that they were built too rigid and the installed boiler had developed all sorts of stress cracks and failures. Now both their steam engines are out of service, awaiting another set of new boilers.

Now, for the idea of building a new steam engine to use in regular Class I usage, there have been advancements in metallurgy and machining that would be helpful. But steam engine technology has really not had any major developments. Roller bearings were a huge efficiency booster, but those were known and used in the '30s. The Lempor exhaust, which used two stacks and pulled a vacuum on the back of the cylinder to improve efficiency, was supposedly a pretty big game changer but came too late to the party to make a difference. Definitely rotary cam poppet valve valve gear, as experiemented with but improved to be not-so-fragile. Perhaps a higher-pressure, "ultra-max" boiler like on a NYC Niagra. Other than that, there really hasn't been any major advancements that were successful. The D&H experimented with some ultra-high pressure, multiple-expansion water tube boilers but said "every time she went out, we had to send half a machine shop with her." Could the maintenance woes of it be solved today? Maybe. The Chinese were using steam engines into the late '90s, but they were basically just reverse-engineered 1940s American designs that were set up to run on terrible-grade coal, there was no real pushing the envelope there. A few years back some company tried to purchase the last remaining ATSF Hudson, #3463, to develop a new "zero carbon" fuel source that used torrefied wood and compressed coal dust (How is that zero carbon?) but they were just trying to develop a new fuel source in hopes that would sway the railroad industry back to building steam engines. That program flopped and nothing was done to #3463 (Thank god, because they said that when they were done "it would only resemble the starting point in the loosest sense") partly because the group that sold them the big Hudson did not own it. In the end, I think steam's days of ruling the rails over. Steam boilers are still too maintenance-intensive, they are still perceived (perhaps rightfully so) as being dirty, and they have weird powerbands thanks to the correlation of pistons being directly connected to the drive wheels. A steam engine is a lot like driving a manual transmission car in one gear at all times. Either it's a powerhouse down low and then inefficient and slow up top, or it struggles to get moving but then runs like a scalded cat at 60mph. Electric motors don't have that issue.

Now, building new steam engines to use in tourist usage? That has a lot of merit. A big part of the cost of restoring a steam engine comes from the fact that you are undoing 60-80 years of decay from oft-improper storage. And then sometimes you do that and get it operating and discover that the engine still has more issues, like the Atlanta & West Point #290 crew, who got it operating and then found that it had severe frame damage that resulted in constant bearing issues and forced it into an early retirement, or the same issue with CN #3254 at Steamtown. It results in a more reliable engine that can operate more frequently. It also allows you to dodge the whole "historical fabric" debate from preservationists, because it is an all-new build and you aren't replacing parts of an artifact or making upgrades like roller bearings or stokers. A big reason the PRR #1361 restoration stalled out was that the boiler was worn too thin to really use (PRR pinched pennies and built their engines to a cost, and the boilers were built in the same vein) but groups didn't want them to replace the original boiler. Also, it dodges the whole issue of cities/states/museums getting grabby late in the game and having cold feet about you taking "their" engine away, like what derailed, pun intended, the D&RGW #223 effort. And currently, if you want to operate a steam engine, your restoration candidates are limited: you have to work with what is still extant, what will work with your layout (if you're a small line with light rail, you can't go restoring a PRR I1sa, and if you have long trips you can't make do with an 0-6-0 yard switcher at 10mph) and what you can get readily get your hands on from local parks/cities/museums. Does your operation need a fairly heavy Pacific that can tow a 12 car train at 50mph? Or a Consolidation with decent power but low axle loadings? Build one. It also lets you create engines that are no longer extant. If your operation is running on say, old Reading tracks, and you want a Reading steam engine, but no Reading G3 Pacifics were saved (and a G3 is unique enough that you can't doll up another Pacific to look like one easily) then you can have one made. Or everyone bemoans that no one saved a NYC J3 Hudson, while now one can be built (and I sincerely hope that the T1 Trust's success will inspire a group to build a J3 Hudson from scratch)

There was an interesting, but ultimately nonviable, proposal put forward by some people a couple years back for a pair of "universal" steam locomotive designs for tourist lines to operate. The idea was that by using a standardized design it would be cutting down on custom parts and make them cheaper to purchase and operate by more cash-strapped short lines. I believe the two configurations were a 2-6-2 Praire and a 2-8-0 Consolidation. The idea was they would use the same cylinders and cylinder saddles, the same smokebox segment, the same drive wheels and axles (63" was the height that was agreed to be best) and cab and tender. They would be saturated-steam (superheating adds power but more parts to maintain and repair), Stephenson internal valve gear (very simple) or Walschaerts valve gear (very common and well understood), and roller bearings on all axles (less fiddling with adjusting clearances and packing bearings) and a welded firebox crown sheet (reduces risk of boiler explosion, as shown in the Gettysburg #1278 meltdown). It was a great idea, but you'd essentially have to find a company that was willing to get into construction of all-new steam locomotives and you would realistically never sell enough to make a profit or bring the cost that far down.

wvumtnbkr said:It's totally possible that this is my great grandfather in this picture.

I still remember when they brought this engine out after it's "restoration". We followed along in my grandfather's car and watched it go around horseshoe curve.

That's awesome. I'd love to see the #1361 reassembled and operational. That poor engine has gone to hell and back.

Reports on what happened with #1361:

"1361 derailed during one of the shuttle runs from York to Hanover Jct. on the NCRR. Unbeknownst to the crew, the derailment dislodged the grease cake in one of the DB cellars, causing minimal contact between it and the axle journal. No immediate issues were discovered once re railed, as the slow speeds of roughly 10 mph did not generate enough friction to cause overheating. When the engine saw mainline speeds during a ferry run back to Altoona(?) that dislodged greasecake didn't provide adequate lubrication and overheated the axle/DB somewhere near Lewisburg, PA halting the move. Water was used in an attempt to cool the overheated axle/DB that had also caught fire, but supposedly resulted in the axle and DB fracturing from thermal shock. The engine sat there for some time until repairs were made for it to be hauled dead in-tow."

"It was not a bearing that caused the grease cake to melt out, it was a loose tire at York that was never reset, and caused the hubliner to run hard against the journal box, due to minimal lubrication on the hub this in turn heated up the box and the axle, causing the grease to overheat and runout, which then made the bearing fail. I stuck dimes in between the tire and the wheel center to prove my point to the crew. I showed the loose tire to the crew at York and they took no actions, when the tire cooled and shrunk back on the wheel center, it was crooked on the wheel center and caused the hubliner to run in hard contact during each revolution of the wheel. The tire did not come off completely because of the riveted safety plates. The whole fiasco was caused by a defective brake system causing the brakes to constantly reapply on the locomotive as it was pulled back to York and to boot not one person from the operating team, knew how to cut the driver brakes out. From an operations standpoint, the crew wouldn't even need to cut the driver brakes out. A vigilant engineer would see brake cylinder pressure creeping up on the gauges and thus bail off any errant application (maybe due to a faulty distributing valve?). One would like to believe, an unintended, prolonged application of the driver brakes would be heard, felt and definitely smelled long before they heated up a tire to a point it expanded off the wheel center. No disrespect to Mr. Tillger, I'm simply playing Devil's advocate."

"1361 had a problem with the Hub-Liner heating from the 1st day after the '85 re-build; I was one of the original 1361 crew from when it came off the curve.

The events prior to the York trip prompted me to start to back away from 1361; I was asked in two private phone calls to go to the York trip and a call after the York trip to get it back to Altoona! I had to decline: newly married and expecting a child; I was again asked on a trip on what would've been my first "Father's Day"" That hub liner heated from Day One. The Man in Charge (Reason I left) said this was common and it would cool down; it progressively got worse."

PRR #1361 on her first run after restoration. The baggage car directly behind the engine in SP Daylight colors is the Yes Dear, a tool car owned by Doyle Mccormack, who spearheads SP #4449's operation

In reply to kazoospec :

I wouldn't mind seeing some photos of #3001, the Mohawk that they have. I know that New York Central had some big facilities in Indiana but it still baffles me that the New York Central Museum isn't in, you know, New York

From today's trip to the New York Central Museum:

I've got a few more on my phone that don't want to download for some reason. I'll add them later if I can upload them. The museum itself was pretty small, probably took us an hour and a half to go through. Their outdoor displays are, quite frankly, in rough shape. Even on a Saturday, there was a fair amount of traffic coming in and out of the neighboring NS yard. Definitely worth stopping if you are in the area. Probably not worth extensive travel to get there.

You'll need to log in to post.