OK I'll help.

I'd like a stiff handle, still debating about an arrow shelf. The bow I shot as a kid didn't have one but it's been a very long time since I've shot a bow of any kind.

OK I'll help.

I'd like a stiff handle, still debating about an arrow shelf. The bow I shot as a kid didn't have one but it's been a very long time since I've shot a bow of any kind.

If you are debating there is something you can do. Make the handle stiff and narrow it a bit. Shoot off the hand a bit and decide if you want a shelf.

See the bow on the left? it was made much like the one on the right, with no arrow shelf. I then glued a bunch of layers of felt together, and used the wrap to secure it to the bow. Instant arrow shelf after the bow was shot a bit. I guess you can't see the shelf in that photo, but you can see how the wrap bulges outward.

FYI, that's more dacron. If you shoot it long enough, it'll look like the one on the right- worn, kinda ugly, and frayed. If you like that look, go for it. If you don't then use something else.

hold tight, i'm doing some sketchup stuff for visuals

Here are some plans for roughing out the handle that I used for the bow on the right in the picture above.

After roughing out, it looks like this:

Obviously you'll have to round everything off and adjust the handle for comfort, but you get the general dimensions from that.

Rufledt wrote:

I think I screwed that one up. I can't really measure now. Make that 6" into a 5.5". This way, the bow doesn't start to narrow until the handle is already well on it's way to increased thickness. You don't want any bend here. Not only could it stress the handle into set (or breakage) but it would add stress to the glue joint, popping it off. The bow on the right at the top of the page actually has almost no glue left holding on the handle, that was back when I was using a bad bottle. The burn looking edge is actually from heat treating (i'll get to that after the successful completion of this bow, but I won't heat treat this bow). That edge wasn't attached because the glue popped off, so it was extra thin and got super hot, turning it black. This bow still works because the wrap keeps the main board from bending (in this case, the handle wood is more of a splint than anything). Wood won't break unless it bends first, so even though this point is too weak, it won't break unless I unwrap it.

Edit: I have the bow strung, will get some tillering done this afternoon. Will be shoot able this coming week, but I'll probably be doing a lot of finishing work/handle and tip shaping. After that I can give some shooting how-to type posts in case anyone needs that.

I did the basic shaping and glue-up of of the handles (going for stuff handles w/ an arrow shelf), and the bow tips.

I took some pictures of the boards and the end grain. Once the clamps are off and I start to do a little shaping I'll post up some overall progress shots.

Oh, and about clamps, the local Costco had a 16 pack of various sizes for sale and a decent price so I picked those up. My first impression is that they aren't all that great, but they work OK.

For handles and tips, it's not all that vital that you use top shelf clamps. The grey and green clamps I use for pretty much everything are sold for 99 cents each at home depot. I'm looking forward to the photos! That goes for anybody out there following along

Tillering update!

I last left you with the long string. I tried shortening it, and ended up not shortening it enough to achieve a brace height. It was stable when pulling the string a bit, but it wanted to reverse string itself.

This is because of the reflex. the tips want to bend that way, and the shortest point between them is the path that string takes. For this reason, a recurve can be subject to twisting. At normal brace height, this longbow will be perfectly stable, but a recurve (if recurved enough) will want to acheive stability. If the bow is out of alignment, the string can reverse, causing a break. Asiatic recurves are especially subject to this.

I did some more wood removal and checking until it got about far enough to brace:

I removed the string, moved the knot to be shorter, and restrung it:

Woops, still too low. It looks slightly out of alignment, so I removed a tiny amount of wood from the limb on the right (I measured tip deflection, it was off by about 1/4") and shortened the string again:

Now the string is 6" away from the handle. Awesome. It's out of balance, but that can be fixed. At this point, you can do more than measure tip deflection, you can measure how far the string is the from limbs at various points along their length.

Remember, pencil marks and THIN, even wood removal. Fix any problems with balance (by removing wood where it isn't bending enough) before bending the thing any further.

After removing some wood, you may have to exercise the wood by pulling it a little bit (not near full draw, that might break it) about a dozen times. You can do this on the tillering stick on a scale to make sure you never exceed (or get close to) final draw weight, to prevent over stressing anything.

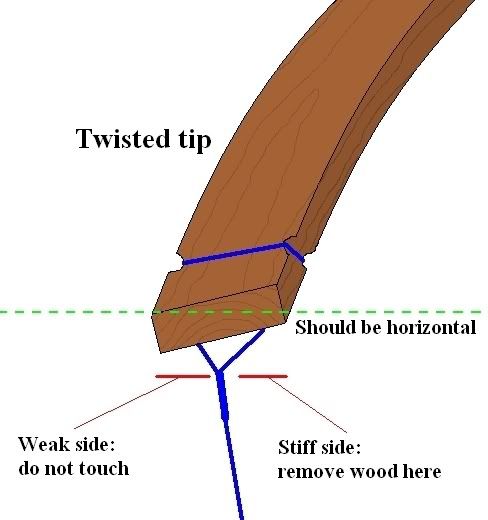

A common problem that I encounter is limb twist:

I'm not holding that crooked- that limb twist and bends to one side. to fix that, remove wood from one side of the limb

The limb will twist toward the weaker side. also, keep in mind a minor twist in a limb is not the end of the world, in fact, it won't matter one bit. My wife's bow has propeller twist. It looks exactly like it sounds. The string ends up in the middle of the handle. What did I do to fix that? I carved the tips at a 15 degree angle, so the string pulls straight on the tips. That probably wasn't even required. This twist isn't so good, though, so I will fix it.

Remember, you should only bend to about half the total draw weight. When everything is balanced, bend it another 10# and check the balance. Keep doing this until you are at maximum draw weight (probobly only around 15" of draw) adn then remove slowly until you reach maximum draw weight at around 27" of draw (or 1" short of your draw weight, it will drop to that draw weight at your draw length after break in). When I say remove wood slowly, i mean really slowly. As the wood gets thinner, the amount of wood you remove will be a greater percentage of the wood's total thickness, so you have to take fewer passes. Don't screw this up. If you mess up on the long string, you have a lot of time (and wood) to fix the problem, but once you reach this point, a mistake could cost you 5# or more final draw weight. I'm only at maximum draw weight at 20" or so, so I have some work to do. Some careful, slow, painstaking work for what might end up being my fastest shooting bow yet.

I've mostly only made bows in the 35-45# range, since that's what I generally shoot. For targets, there really isn't a need for anything more, since it's accuracy and not power that counts. Plus, at 45#, I can draw my current most-used longbow all day without tiring out. For about a year I used that hickory/purpleheart bow on the first page of this thread. That one draws around 55#, but the tips could've been lighter, and there was no 'perry reflex' glued into that one, so there was room for speed improvement. Purpleheart is also crazy dense (meaning really heavy) and actually not all that strong in compression (the job I had it doing) so the bow was doomed to be average. I sold it to a guy who planned on hunting with it (it had more than enough power for that) and I've kicked myself ever since.

That's only at about 16", and as you see it isn't perfect. The bend is mostly near the handle, and the limb on the right has a tiny hinge in it. It probably won't be finished tonight. Once it is, the tips, handle, and finishing stage starts. More on that when I get there.

I wasn't very clear about the fixing a twisted limb thing. This diagram will help:

Also, here's a more bendy photo:

See any tiller problems? I do, but i'm not done yet. That's at 20" btw

Pro-tip time.

When the bow is strung at brace height, you can remove wood without unstringing it. This is a huge time and energy saver. Clamp the handle down to whatever with the belly side up. Remove wood, exercise the limbs, and check tiller on the tillering stick (it's hard to really check when it's clamped down). Repeat. You will still want to unstring it occasionally to check for set. Remember, it will take set where it is stressed. If you area is taking more set, it's a good bet that it's overstressed there. You can't fix this by removing wood elsewhere, once set happens it stays. There is a way to fix it later if it's caused by mistakes during tillering, but not now.

String making (more specifically string twisting) can be done with a drop spindle kinda thing:

This is a pic of someone using a drop spindle to spin yarn. Yarn is just a bunch of shorter fibers held together by twisting (sound familiar?). The person spins that dealy with one end attached to the string. The inertia of the spindle keeps it spinning and it continuously trists the string. I don't have one of those, I use a spring clamp. I don't have a pic of this since the clamps are still at my friend's house.

I've also heard of someone using a power drill to twist the string, but the drop-clamp method works very well for me. It can also help keep fibers together and keeps them from untwisting before it's done.

Good news! I finished tillering the bow today. No word yet on the final draw weight. It is currently around 55# @28 but It hasn't been shot in yet, nor is it finished. Generally, you don't lose more than a couple pounds each, so i'm guessing it will settle around 50#, exactly my goal. One limb is twisted a bit, but not problematic. Here's hoping the first thousand shots don't end in a busted bow.

I'm guessing it will be alright, and that I could've gone heavier, but i'll go over that tomorrow with pics and all of that. I'll go over actual laying out of handles and tips and stuff along with that, most likely.

I shot a christening arrow into my ceremonial box full of discarded People Style Watch magazines that my wife doesn't need anymore, and it didn't blow up (does anybody want a free-sourced target build post? It's only like 3 steps and the targets last quite a while, and can be recycled anyway after they're worn out). Generally people suggest shooting about 50 half draw shots, then 50 full draw shots. This was a 3/4 draw shot. my bad.

What I did notice was a great deal of hand shock and the string slapped my wrist (not wearing a guard). This is to be expected because the tips weigh a ton. I haven't thinned at all from the rough cut out stage, other than rounding the back edges to prevent splinters from lifting and rounding the belly edges to stop from cutting into the string. Lighter tips means more speed and smoother shooting. Think of it like unsprung mass. Less is better for ride and handling, but try to make your suspension arms and wheels too light and they might break from weakness.

WAY future to come: After finishing this bow i'm gonna do a post on making worse performing bows better by giving my current bow that i'm using (and will replace with this walnut one) more power and adding lightness in all the right places. That one is oak, and what i'm going to do worked on my wife's oak board bow, so you oak board people better take notes! Do the stuff to your second bow, never risk breaking a working bow unless you have another one to shoot. Get your heat guns ready, you'll need them.

Yesterday I continued the tillering process (figure out where to remove wood, do it, bend it a bit to get it used to bending, then check tiller again) until I got to about 50# @ 26". Here's a shot at about 24":

I don't have any shots of further tillering, but once you get here, slow down. Remove VERY little wood at a time.

Tillering stick construction tip: see those 2 boards on the bottom? I nailed those to the stick to make it easier to attach the base. Unfortunately, I put them too far forward (close to the notches) When I pull the string down, my knuckles hit those boards. Not cool. Make sure you have finger room.

I did get a full draw, completed shot:

Awkward cropping, I know. Unfortunately I wasn't aiming straight on, so it's hard to see how balanced (or not) the thing is. The bottom limb has a good deal of twist, but I'm gonna ignore it. From this shot, it looks like the bottom limb is bending way more. In truth, the top limb deflects about 3/8" farther. It's the twist that messes with the way it looks in the photo.

I pulled the bow a bunch of times and shot it once. The thing shook like crazy and the string slapped me in the wrist. This is called limb shock, and it is caused by all of the extra weight in the tips. The string slap is caused by the same. The heavy tips slam the string straight, and the momentum pull the string, causing it to stretch. A longer string temporarily means a lower brace height temporarily, causing it to smack me in the wrist. This bow is braced around 5 1/2" from the handle, high enough that I shouldn't get slapped.

Now, on to lightening those tips. With the bow strung, make sure to mark where the string falls, and where you can remove wood

You should also keep track of where you want to narrow the tips. In this case, I am removing wood mainly from one side, because the limb is twisting. This will cause the string to be slightly more centered, but still pretty far off.

Once you shave off the wood, you can start shaping the tip overlays as well:

Notice the hard edges left by all of the wood removal? Round it. Be sure to round the edges in the string grooves, because the rounded edges before got shaved off.

At some point it is a good idea to put the string on and get a sense of how deep your string grooves are.

Clearly these are deep enough, probably too deep. On the left side of the string, you'll see I haven't done much to remove weight yet. Mainly because this wood is almost all superfluous. The string will be pulling the other way anyway.

Then I draw a line on the bottom a little ways up (usually 5/8" down from where the hickory meets the cherry) straight to where the limb becomes thick and unbending, 6 inches away (and slightly thicker here, making the line slightly slanted) Then shave the bit of wood off.

Then I start rounding more things off. I thin the wood to the left of the nock to almost a bladed edge, about 1/16 edge. I'll thin it out some more later, this is just roughing.

Now it's time for the other tip. I haven't done the handle yet. I still have to get the other tip. I had a long day today so I didn't have a good deal of time for bow making. Tomorrow I may have more time, but I probably won't get to wood finish until later in the week. FYI, it's not really much different from doing furniture. Well, I don't use varnish or shellac, but those options do work.

any questions/comments/concerns?

Another tip- When using a new string, expect it to stretch a lot. I said before to first try 3" shorter than the distance between the string nocks, but go for 4" at first, and then adjust. It will stretch a lot at first, but it will settle in. I just put the new string on (that I made in an earlier post) and watched it go from 4" brace height to sitting on the handle in 30 seconds.

Bad news everyone! One of the cherry tip overlays got a crack in it. At first I thought it was a glue joint failure, but on closer inspection it was an early growth ring that let go. What yo probobly cant see in the tip info post is that some people glue them on at an angle, so the tension forces them down into the back. I don't, and I've never had a problem. I suspect this has to do with breaking in a new string. When the brace height is lower, the limbs arent bending as far. However, the limbs put more stress on the string. The angle is also more forwards than down, which puts stress on the nocks. This bow in particular has some reflex, so there is considerably more tension at brace compared to other longbows at this draw weight. Add that stress together with an early growth ring and crack!

Titebond glue makes a bond stronger than wood itself, so gluing it back may be all I need. Im also going to reshape the nock slightly, lowering the string to where it doesnt pull on early growth. Nothing here was required, however. The tip gets thicker the further in it goes, and when the knot is tight it wont stretch or loosen. The nock cracked, but the string didn't slip off because it would have to loosen itself. If this plan fails I'll plane off the cherry and stick some other wood on there (like oak or maple) that I have used before without a problem.

Handle time!

Handles are like tips, there are many ways to make them, most of which work quite well. There are some considerations:

1- Fit. You want it to be comfortable, you want your hand to be able to push on the handle without imparting a twisting force. When shooting off the hand, you want to be able to put your hand in the same spot every time. Imagine trying to shoot a rifle when, every shot, the barrel will be at a slightly different angle. Good luck with those groups.

2- Paradox. The arrow isn't shooting straight ahead. The string will be pushing it into the handle, and the arrow has to have some flex to deal with this. The wider the handle, the more the arrow has to flex (lighter spine weight, generally). The more center shot the bow is, the less spine weight matters.

3- Strength. The handle is under a great deal of strain, and it needs to not break here. It also has to not cause splinters to lift, which can travel up the limb and cause a break.

Lets look at some examples from paleoplanet.

This is likely what you will get with a bend in the handle board bow. It can't narrow here, because it is bending there, so it isn't any thicker. Some bows have been found with working narrower grips, but they are insanely difficult to tiller properly. Notice the leather wrap. If the archer always grips so his hand lines up with the top of the grip, he has a reference point for consistent grip.

This one has a tie-on arrow shelf. Notice how the shelf is arched. Do that. you want it touching one point on the shelf (and one point on the side of the bow) not a whole long thing. Also notice the leather on the side where the arrow goes. If you don't do that, the wood scrapes against the bow and makes noise. Noise scares deer and they run off. Also notice the angle of the handle. It's a little closer to the angle on a pistol grip. Some people like that, some people like flat longbow grips. I'm used to more flat ones (easier to make) though I have made pistol grip ones. Whatever you find comfy is what you should do, just remember that with working handles (which are more effecient, btw) you can't have a pistol grip.

Notice how this one comes apart. It helps if you need a bow to be more portable than, say, a plank of lumber. You can buy the hardware at certain places.

That one is kinda S-shaped. I made one of these, and it took a good deal of work. It is comfy, though. That pic isn't my bow, but the one I made to copy that one is what I'll be modifying in a later post for more performance.

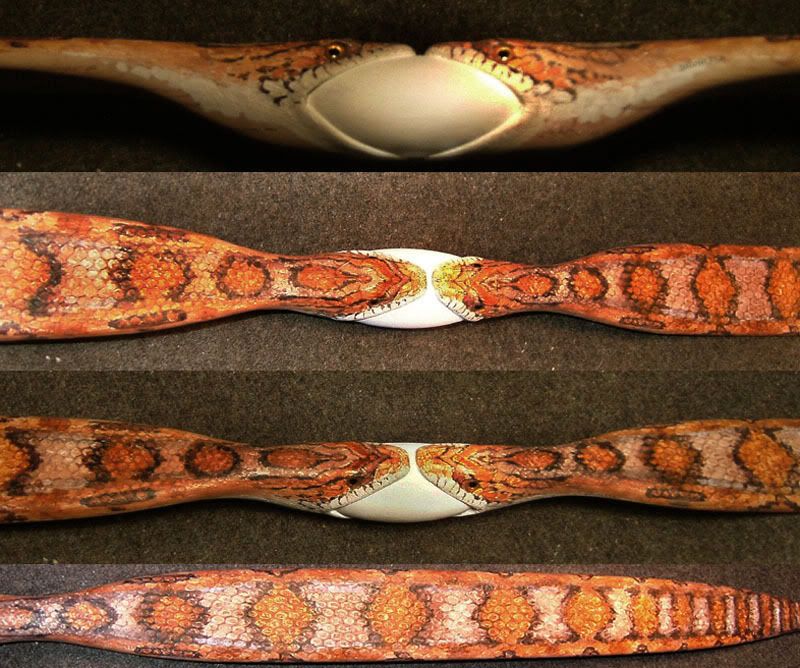

People have even gotten 'artistic' with the carving. Some are even sorta NSFW.

There's a clean example. It's a snake skin backed bow, so it's kinda clever.

There are lots of ways to wrap the handle. Leather with braiding, string, cloth, nothing, all fine options. Some people pad the handles. I wish I had a shot of my uncle's handle that he made. It's crazy awesome.

One concern, permanent leather grips can absorb moisture and lock it in. No finish can keep moisture from absorbing into the wood, which can cause it to rot.

I have plans for this handle, but nothing that I can do right now. Now that the string is on the bow, there is some more of that we have to do, and some wood finish, soon to come.

Late night update for anyone still reading along: Regluing the tip worked. No more problems. Yet. Also the string appears to have stopped stretching. Today I was occasionally stringing, drawing, and shooting an arrow into a box. The tiller is changing slightly, which can happen. What was once the stiffer limb is now bending 3/8" more at brace height. No idea about full draw, because my tillering stick is now at my friend's house. Looking at a mirror, I can't see too much of a difference, but at full draw the tips are back like 15", so 3/8" wouldn't be easy to eyeball.

This happens a lot. Generally, for a hundred shots or so, you should shoot a dozen shots and then check the tiller. Shoot another dozen, check again, etc... If there is a serious tiller problem that was hidden, it will manifest within this range of a hundred shots or so. It may still take set slowly over a few hundred more shots, but once you reach 1,000 (not hard if you shoot a few rounds of 6 arrows a day) it should have stabilized. By stabilized I mean it will stay that way for decades. The tiller can still change if you expose the bow to overly damp, humid weather. In this case, if not protected, the bow can take more set. If you are exposing it to extra dry weather, it will seem to gain draw weight and speed, but it may break on you. There is a range of moisture that wood seems to like, but generally, if you don't feel the dryness or humidity, the bow is probably fine. If you're lips are cracking, it may be too dry. If you can feel the humidity taking the life force out of you (like it does to me) then it's probably too damp. Whatever you use to keep your house comfy will do just fine for the bow, though houses seem to err on the dry side.

There are wood finishes which slow moisture, but none of them seal the wood like you might think.

Also to come, I did a little more string-making photography today. It's called a 'serving' and it will assist in holding the arrow on the string, and also extending string life. Why didn't I do this before when making the string? Because having the stretched-in string on the bow makes the process a whole lot easier. I'll probably post the pics tomorrow.

Rufledt wrote: Late night update for anyone still reading along:

Oh we're reading... Just taking notes rather than come up with things to say ourselves. Teach us, we'll listen.

Here's my progress so far.

My two boards from the hardware store. Neither was perfect, but out of about 20 boards these seemed to be the best.

The glue up was pretty run of the mill so I didn't take any shots of that. I added the handle and tips, then did some basic shaping on the band saw.

I did some work on the tips to get it ready for a tillering string:

The wood I chose to add some accents is reclaimed old growth redwood from some other projects I worked on. I'm worried it might be too soft, and that this area of the handle will suffer. I tried to extend the fade of the handle down into the oak of the belly because one build along I read mentioned this helps avoid extra stress on the glue joint and the other woods in the handle.

This my tillering board, again built mostly from leftovers from other projects. I'm just using some paracord for tillering, and will probably buy my first real string instead of making my own... one step at a time.

I added the peg board to give it a uniform visual reference. It may not be perfectly square to the tillering stick, but it's pretty close. I may end up covering/painting it at some point and putting on more accurate reference lines.

I wanted to make sure that I wasn't pulling with too much weight during tillering, so I weighed my floor jack and it is now my handy 30 lb. weight. I know I can now safely pull to the third notch on my tillering stick. I have plans for a pulley / scale addition soon.

With some more wood removal I rechecked and found I could safely make it to the fifth notch, that puts it at 14 inches of draw at 30 lbs.

The handle is 10 inches overall so that should give me enough room to cut an arrow shelf and still end up with a fairly overbuilt handle. I'm thinking of adding a fiberglass backing for added margin, but I don't know if the additional tension strength in the back will be bad for the belly.

Excellent! so people are still with me! After a few days of talking to myself I was having doubts.

That looks like a pretty sweet set up you got there, certainly better than my first. I've never had a big garage of my own (or a permanent place to live) since I went to college, so i've always had to make due with portable small things. A pully/string scale would be optimal, as it lets you stand back and watch it bending, and i'm sure it would give you more accurate weight measurements than my crappy bathroom scale. I've seen people with the whole rig attached to a wall with a grid painted on the wall behind it. I can't imagine how difficult it must be to make the grid perfect!

Looks like you have some good boards, especially the one on the right. Don't sweat it if they aren't perfect, they never are. If you are close enough to perfect you won't have a problem. I actually just found a little pin hole knot in one of my unbacked red oak board bows, and it never caused a problem. As for the redwood accents, don't worry about the softness. On the tips it looks like the string rests on the oak anyway, so you won't have to worry there, and for the handle the most important thing is that the wood glues well. Certain hardwoods (especially very dense tropical ones) don't like being glued. I don't know anything about redwood but most woods from north america are fine.

I have heard the fade trick with handles, too. I found that a good bottle of glue is the most important. It seems that whatever I do, a good glue bottle never fails and a bad bottle always fails. It looks like you have more than enough handle thickness to be able to shape it however you want. 10" long is also far more than enough. Is the board the full 6' long still? If so, 10" should be fine, but if you are much shorter (like, say, 5') then that handle would be taking away wood that the limbs need to bend. Luckily, 6' longbows are longer than necessary. The length means safety, which means you won't be as likely to break your first bow.

I can't say if fiberglass backing would cause more problems than it would solve, as I've never used it. I have noticed, however, that red oak tends to like taking set, so anything that could increase belly stress might be problematic. I've also only broken 1 red oak bow outright, and it was because of a backing I screwed up due to inexperience. I would say just go bare wood on the first run. almost all wood is stronger in tension than it is in compression anyway, so a rectangular cross section (with rounded back edges, remember!) will usually be strong enough in tension not to break, unless you wayy over stress it. Some species of oak (those under the 'white' category especially) have even higher tension strength than hickory, the so-called bad ass of tension strength.

Fiberglass as a backing may even alleviate belly stress, though. Full disclosure: I have no idea what properties fiberglass has compared to wood or sinew, like I said, I've never made a fiberglass bow. Sinew can stretch farther than wood. A lot farther. When people add sinew to the backs of bows, the surface of the back (where the most tension work is done) offers up less resistance, so it ends up needing to stretch farther than the belly compresses to be under equal stress. This means the neutral plane moves from dead center to closer to the belly. Ergo, the belly wood doens't have to compress as far the for the bow to bend a certain distance. Does fiberglass do this? No idea, but it might. If I were you, I'd just go as is. My only issues with unbacked red oak are always compression related i.e. set. If you are worried about a blow up (and don't mind sacrificing some power) you can round the belly somewhat (don't go nuts). This will make for a bow more likely to take set than break if under too much strain, as the belly will have less wood available. Basically, the top of the subtle arch will be under a lot of strain, but it will only be like 1/4" wide, while the 1.5" wide back will be handling tension. The belly will be crushed before the back breaks. This means if you screw up, you will have a mediocre, functioning bow, instead of a piece of firewood. I actually made my first bow like this. Flat back, rounded belly, 6' long. I know I said on the first page my first one was pine and 2nd was maple, but I had forgotten about an oak one in between them. Forget the pine one. That's an embarrassment. The first oak one kinda sucked, too, but those kids I gave it to sure are happy!

Do you plan on cutting the arrow shelf straight out of the wooden handle? Nothing wrong with that, I just find that I like gluing on an arrow shelf out of leather or something, because it gives me some flexibility. Often, a bow will seem to shoot better with one limb or the other up, and the only way to know is to make it and shoot it. After figuring out which side to place the arrow rest, I glue on a couple layers of something. Leather is my favorite. If you glue up a couple pieces of thick leather, you can actually carve it to shape with a knife, much more easily than if you cut it out of the handle. OTOH my friend's wife's bow that we made had a wooden cut out arrow rest and it works just fine. We did pad the thing with leather, though, which can be attached with rubber cement. That way, you can remove the leather and the rubber without damaging the wood if you ever need to replace it.

As for making a string, I think I had half a dozen bows done before I even bothered to try. Now, I'll never buy another string. You can buy strings with a loop on one end and a knot on the other. I would actually recommend that instead of the double loop ones, because those have almost no adjustability. OTOH, I've only purchased the double loop ones in the past. What always got me was when I needed a string for a new bow that was a different length, I had to order a new one, even if the old one wasn't being used. It couldn't be adjusted.

String serving time. First off, what is it and why do you need one. A serving is wrapped around the part of the string where the arrow nocks and you grab. many modern arrow nocks will snap on to the string, and the string I made is too small. It's also a 2 ply string, which isn't particularly round either. A 3 ply string is better in this respect, but takes a little longer to make. The nock makes for a thicker string without adding significant weight, and it also is somewhat abrasion resistant. Standard dacron isn't great with abrasion. Observe:

At one point, I was using dacron to serve dacron strings. It added diameter, but wasn't particularly good at abrasion. It also would unwind, and started to look terrible. This is only on the part of the string where the arrow nocks. The metal thing is called a string nock (i'm telling you, the word 'nock' is used for anything) and it a reference point to make sure I nock the arrow on the string in the same place every time (see! nock can also be a verb). Where I didn't serve was below this point where the string occasionally hits my arm guard.

See? It doesn't look pretty. It looks like a string that was never waxed and used for thousands of shots. This wear, however, is entirely on the outer fibers of the string, which just so happen to be the strings that take all of the tension load. Bad news. I've never broken a string, though, so maybe not so bad news.

I no longer use dacron, I use actual serving material.

If you buy a dacron string, there's a good chance it has a serving made of this. You may notice the serving isn't in the middle of the string, but slightly off. Put the string on such that the arrow nocks higher up on the serving, so the lower part of the serving hits your arm guard.

There are many ways people have tried tying on a serving, many of which fail. The method I use works, (stolen from those bowyers bible books) and i've never had one loosen. First, figure out where you want to put the serving on the string while the bow is strung. Put a sharpie dot where you want to start it or something. I always start at the top of serving area and work down. Now, unstring the bow. Separate the 2 (or 3 or whatever) plies that make up your string and slip the serving through a few inches.

Now, string the bow. Grab the string and wrap up from this point about a centimeter, and then start wrapping downward, fairly tightly.

Now, keep going for like 6" or however long you want the serving to be.

At this point, it's going to get tricky. Now, you'll need a bunch of extra material. Hold where you stopped wrapping tightly with your finger, and start loosely wrapping ahead of where you were, but back toward the serving like so:

After a bunch of turns, lay the string flat against the serving and continue wrapping along like you were originally. The extra loose wrapping you did at first will unwind as you wind up the serving.

When you get wrapped far enough to unwind the extra wrappings, you pull the loose through under the wrap tightly.

Cut off the extra and you're done. I had to wrap the serving again over the first one to make the string thick enough for the arrows to clip on. I went from too narrow to slightly too thick, but it'll work.

In this pic you can kinda see where I added a 'serving' of artificial sinew over string where the extra short strings from the loop end. This will smooth them out visually, but it is not neccessary for well made strings.

Rufledt wrote: Hey Keith, did your wife ever show you how to use the stringer?

Not yet, I've been doing other stuff and the bows got put away to keep them safe. Maybe this weekend I'll make her show me.

Yeah life can get in the way of archery. I was really into it for a while and then took around 4 years off, until one of my friend's here wanted to me to show him how to make bows, now i'm back into it. I just wish I had the sense to move my stack o' longbows with me when I moved to the east coast. i only brought 1 bow! It's not even made of wood, it's one of those crazy anodized aluminum/carbon fiber target recurves. I didn't even shoot the thing for 2 years after I moved here, it just sat in the bow sock. Life happens. It's just like all of this schooling I keep going to. It keeps getting in the way of my video game life...

So here are some more clarification photos that I probably should have posted before.

Here's a shot of the handle of an oak bow I made. You can see this is the one that is s-shaped. Also in this shot you can see the arrow shelf, made of felt I think that I glued up and wrapped onto the handle. This is looking at the back of the bow. You can see I glued a thin piece to the back of the bow, hoping to give the handle some more ridgidity, lessening the chances of the handle popping off. So far it works, but this is also the first bow made with a fresh glue bottle, so that may be more to thank. Like I said, I've always had handles fail when the glue was old, and never had handles fail when the glue was fresh.

Here's a shot of the back where I found a tiny pin knot. You can also see many lines in the oak wood. Oak has more than just ring lines, it has radiating lines. These run perpendicular to the rings. Rings are porous, radiating lines are dark and solid. Here's a better shot:

You can almost read what angle the wood is cut from the tree by how these lines cross each other. If the wood is dead straight, the rings (more specifically, the pores which are like straws) will go straight along with the radiating lines, like on the photo above with the tiny knot. This means that the wood fibers are going straight, which is desirable for bow limbs. That shot is on the handle, which is cut across the grain, so these 2 lines form more of an angle.

Another kind of marking found on oak (more often white oak) is subtly in this shot:

It looks kinda like the nike symbol on it's side in that shot. Quater sawn white oak emphasizes that kind of marking, which is why mission/arts and crafts style furniture is made preferably with that kind of wood, cut in that way. Slightly off topic, but white oak is amazing wood, moreso than red oak. It is denser, tougher, and the pores are not straight through. barrels made from white oak are waterproof, and the wood is closed cell, making it resist rot better than red. The USS Constitution, nicknamed Ironsides for it's tough cannon ball stopping hull, is made much out of white oak. Also live oak, one of North America's densest woods. White oak tends to take lots of set, though, unless heat treated. It can be found at any half decent lumberyard by the ton.

Moving along then... Remember this stuff?

It is applied when the bow is strung. It's like a push up thing with wax, and you just run the string through the wax to get some on the string. Then, rub your hand up and down the string, creating friction heat. This will soften the wax, and also force it down into the fibers. If you feel like you're going to burn your hands, then rub it in with a rag, you pansy.

I haven't done finishing on my bow yet, but i'll go over it real quick and post pics later when I do. Basically, treat it like wood furniture. You'll want to sand/scrape off tool marks while removing the minimum of wood from the limbs (as this could change tiller). Once you have the tool marks out, do the general sanding in from 100ish grit to 200ish to 300ish. If you are using oak, you can actually go to 600 or higher grits, as the wood is actually hard enough to take a polish. Don't use steel wool. Bits of it will get caught in the pores, and that doesn't feel good to run your hand over. Whatever finish you use, just apply as per the instructions. This is wood after all.

I use this:

Tried and True brand polymerized linseed oil. When you go to the store and buy "boiled linseed oil" it isn't actually that. It is linseed oil with chemical driers, to help it cure faster/harder. That finish will work beautifully (as will shellac, polyurethane finishes, etc...) but Tried and True brand (available at woodcraft, not home depot) is chemical free. I think it's even food grade, full of yummy omega 3 fatty acids. Don't drink it, though, since the can says "ingestion of large amounts may cause nausea." Chugging boiled linseed oil from home depot may kill you.

Here's the really annoying thing, the company whos products are at home depot own the name "Boiled linseed Oil" so their oil, which isn't boiled, is called that, while Tried and True brand which actually sells pure linseed oil that has been boiled, can't be called that. Stupid laws.

Flaxseed oil can be substituted with any vegetable oil, really, and many even use straight lard. Lard is better at moisture control, though. For moisture control on mine, I coat it (after the oil has cured and I have applied many thin coats) with paste wax, multiple thin coats. Then, every few months just put on another coat of wax. This is the beauty of wax and oil, more can be added and it looks nice. If you varnished the thing, you can't add varnish without the finish building, and eventually cracking. If you try to put oil over the varnish, it can't soak into the wood and never cures properly. You can still wax over about anything, though. More on that later, I'm gonna shoot some more break in shots and make myself some dinner.

This page is getting rather picture heavy again, I hope not long now until the next page can start fresh. There really isn't a whole lot more to do with this bow anyway. In fact, I could slap a bunch of oil and wax on it and shoot it until i'm old and grey, it would just be ugly.

Is anyone out there itching to get a beginners shooting how-to before I move on to finishing? I'll probably do the finishing at the same time no matter what, but I just want to gauge where people are at with respect to actually using these things.

In the interest of rolling this on over to the next page, here are some shots you may find interesting.

First up is a shot from the highland games somewhere in Wisconsin from a while ago. That's my uncle who got me into archery.

That is a door from a Cadillac STS, early 90's I would bet, from a junk yard. Yes, the arrows went through it. The top one went through the outside and a speaker before sticking out the other side. The bottom one got hung up on some crash bracing I think. Despite my uncle's large, sunburned muscles, he was only shooting a mass produced 60# recurve bow, and those are somewhat heavy (but not unusually so) arrows with standard field point tips. People forget what kind of power these things can have. Don't fool around, they can be dangerous. If that door were on a car, that guy would have a hole in his leg AFTER the arrow went through the car door.

Remember how I said a leather handle can lock in moisture and cause handles to rot? well I found a pic:

This bow was shot multiple times a week for years, so the rot doesn't set in right away. This bow, furtunately, is a take down. Another handle (called a riser) is made, and the limbs are just attached.

Finish time. For those of you who are interested, here's my workbench:

There are usually more tools hanging, but I've been a bit messy lately and I haven't put them all back. Also a lot of the wood tools are at my friend's house.

Below are some shelves, more tools (in the box), and 17" wheels/blizzaks for my RX-8. They are pretty much new. I bought them from someone who had gotten them for his RX-8 and never really used them, and then I proceeded to not use them. Too bad my wife's car is 4-lug. D'oh.

You'll want these. A bunch of sand paper from 100-400 or so grit. Higher grit numbers are finer, lower numbers are coarse. i've noticed if I start lower than 100 grit, I spend an unnecessary amount of time trying to get sanding scratches out, so I start with 100-150. This first step may take some time. You'll have to remove tool marks. Look here:

See how the tip appears to have facets? That's from me carving out the tips with a knife. The 100 grit or so sand paper should be used until the facets and other scrapes (like one the belly where you removed wood during tillering) were smoothed down. You should work lengthwise, not across the grain. This would prevent scrapes that look terrible later.

On the right is sanded area, on the left is unsanded. Notice how i didn't only remove tool marks, but I did a little rounding as well. Notice the tool marks:

You'll want to get the tool marks out now. Higher grit sandpaper will only make them more visible, and the finish will really make them visible.

This is the belly during sanding. You may think too much wood must be removed , which can risk changing the tiller. In reality, the wood at the bottom of the grooves is doing more work than the tops of the grooves, which are kindof loafing about. When you smoothen out the belly, the load will be more evenly spread out.

After getting it all nice and smooth, go over it with 200-ish grit, then 300-ish. This will take less time than the first round of 100 grit, because they are only smoothing, not removing wood to get out gouges. I stopped at 400 grit. Then, you'll want to wipe off all of the dust before applying a finish.

Here's the bottle of linseed oil open next to the smooth limb, nice and wiped off (with a dry cloth or a tack cloth, not a wet one). I just dunk a couple fingers in there, and wipe it on the wood. Spread it out until the oil is covering everything. Don't soak the wood in it, thin coats are key with the old school oil finishes. Notice the color changing:

You'll notice the handle doesn't look so good. I'm not satisfied with the shape of the handle. I'm gonna sand and finish it later when I get it looking nicer. The color change doesn't really happen on the hickory or any other lighter woods:

This can bring out the different colors of wood, like the tips on this bow

This isn't particularly good looking because the oil isn't uniformly thick, and parts of it are kinda wet. Leave it like this for 5 minutes or 10 minutes or so, then rub the crap out of it with a clean, soft cloth. I used a small cotton wash cloth, something like a cotton terry rag for detailing would work perfectly. It will now look more like this:

Not so shiny anymore. Now, as per the instructions on the can, let it sit for 8-10 hours. After that, rubbing it with a cloth will give it a nice sheen. I generally put more coats on (like 2-5 generally) and then let it sit for a few days. You can shoot during this time, I just stop putting more coats on. After a while (allowing it to cure a little better) I shift to furniture paste wax. Apply as per the instructions on the bottle, in thin coats. After drying, buff the crap out of it with a cloth. That will make it much shinier, and will help force the wax into wood pores. This is especially important when you're using red oak, since the pores are so huge. It may take many thin coats to get the pores filled in, and it may never happen. I certainly haven't done it, but i've never applied more than a few coats of the wax. A couple times a year (or just before and after hunting season) apply another coat of wax, and it'll help resist absorbing set causing moisture/drying out to the point it breaks. I don't have pics of how it looks because the first coat of oil is still curing. Really, I doubt the photos would do it justice. It looks so much nicer in person. I now know why modern furniture makers love walnut. It's easy to work with any tool, it smells amazing, and when it's finished it looks beautiful.

Another great advantage of oil finishes- I only finished the limbs. Later, when I finish the handle, you won't be able to tell the difference. If you try that with varnish or polyurethane, it will show. Shellac layers blend together, though. If, later, I see a tiller problem, I can use a card scraper to remove wood. Card scrapers won't leave tool marks that need to be sanded off (people often use scrapers instead of sand paper) and apply oil again. Many modern finishes are not this flexible.

A word on safety- If you use an oil finish like this, be careful with the rags you use. One method of disposal is to soak them in water, put in a plastic bag, and throw it in an exterior garbage can. Others say you should dispose of it in a metal trash can with a metal lid. They have been known to spontaneously combust. I've never had that happen, and I don't want the first time to happen where the rag can set other things on fire. I always soak the rags. Better safe than sorry. Sometimes I use paper towels to wipe the oil off, soak them, and throw them away in a ziploc bag. Come to think of it, this may be the reason i've never had one combust.

You'll need to log in to post.