In reply to fromeast2west:

Best bet for the pics is just to use an external card reader and take the memory card out of the camera to transfer them. It's faster and doesn't wear down your camera's battery like transferring with a cable does.

In reply to fromeast2west:

Best bet for the pics is just to use an external card reader and take the memory card out of the camera to transfer them. It's faster and doesn't wear down your camera's battery like transferring with a cable does.

I forgot about the cable thing that comes with Sony cameras. I usually use an external card reader, though, since I misplaced the cable that came with my newer camera. Sadly, older Sony cables aren't compatible.

Look what I was up to yesterday:

TONS of black locust. I took home maybe a dozen staves, and now I'm sore. Still, I'm happy about it. I had intended to take pictures during splitting, but I was a bit to busy with a hammer and wedges. Plus we split them in the woods where we cut them (read: where the guy who owned the chainsaw and actually knew what he was doing cut them) and I didn't bring my camera.

I will say I'm exceptionally happy that I drove my van, those staves weren't reduced at all, and they were cut extra long. The guy who's property this was said he's tried everything (including painting and shellacking the ends right after cutting) and they always check just as bad, so he cuts them extra long. That way, after drying, he just cuts the ends down until the checking is all gone. He thinks the shellac/paint method is ineffective for black locust. He had a garage full of these staves, so I believe him.

That oregon ash stave I'm working on just has the bark removed, with the sapwood surface as the back (and belly in many places). This guy said I should cut through the bark, remove the sapwood, and chase a ring of heartwood for the back. This means a lot of extra work will have to go into making the staves tiller-ready. Again, his many beautiful all-heartwood black locust bows told me to listen to everything he said.

Hey Archer how do you like that Mazda2? My wife really wants one of those.

Ran into a problem:

The bow string (and thus the string nocks) are under intense stress at brace height, more so than at full draw. When the bow arrives back at brace height during shooting, it is under crazy amounts of strain. This caused the wood to pull apart. I have never had this problem before, ever. Then again, I've never used cherry as a nock overlay before. Cherry has a reputation for breaking in tension unless backed, but I didn't expect the weakness to manifest here, since it can't bend. How wrong I was!

Step one, plane off the old nock:

I didn't just plane down to the hickory. Wood glue is more than just a surface thing, it tends to penetrate slightly into the wood. This means I had to shave down through the top of the hickory backing to get to fresh wood. That way I get a fresh, glue ready surface. I also rounded the corners on the back of the bow, meaning there isn't much of a flat surface, so I had to shave down into the hickory for a perfectly flat surface.

I then cut a small block of maple:

Then glued it on:

At the time that photo was taken, I was at my friend's house and he was shooting. I planed a lot of extra wood off, filed in a makeshift string groove, strung it, and took a couple practice half draw (and one full draw) shot. Success! Or so I thought... The other cherry nock splintered apart on the next half draw shot. Crap. now I have to do it again (or more accurately, I did it already, just no pictures).

Notice the maple block is pretty long. I'm going to try a different nock design. If this proves to be too much wood, I can always shave the extra off.

This bow is pretty high draw weight with reflex, so the string tension at brace height is exceptionally high. It would seem cherry is not up to this kind of stress. I have used hickory, oak, and maple, and never once had an issue. Maybe in this higher stress bow I may have a problem. Then again, there may be a reason why I don't remember seeing cherry tip overlays on people's bows. Maybe it was just a poor wood match. i don't know. I'm gonna kinda miss the cool cherry color. Maple is a different color than hickory, so it's still kinda tri-tone.

Once I got really into colorful wood mixes. I still have a bow stave glued up and ready to go in my garage. It has an awesome mix of bubinga, hickory, yellowheart, and something else that's dark red and highly flamed. I think I meant it to be a holmegaard bow, but with a built up pistol grip like handle, some perry reflex glued in, and a arrow rest carved into the handle. Maybe one day I'll finish it. One day.

Update on 2 projects!

The walnut bow has 2 new maple nocks, shaped and ready for final sanding/finishing. I'll post pictures up later. On Monday, I was at my friend's house who currently has my tillering stick/scale, and i finally measured the draw weight. It came in at 54# @ 28", and 58# @ 29". My draw length is 29.5", but the stick doesn't do half inches. Assuming the same 4# per inch of draw weight continues (and it should, or start stacking by that point making it 5 or 6# per inch) then it draws 60# @ 29.5". It's admittedly a little too heavy for me, so i'm gonna reduce that just a hair. I want more like 55# @ 29.5.

The ash stave spoke of earlier has been cut to shape and floor tillered. Again, pics to follow. I need to decide how i'm going to do string nocks on the bow before I can proceed with tillering. Also I need my tillering stick and scale back.

I was thinking of going with a tied on nock like these:

Not my bows, but that's the idea. Tie a piece of raw hide or wood (or just wrap with flax) to make a hump that the string won't slide over. I've seen that kind of nock used on bow tips that were too skinny to cut nocks into, which means light tips are very easy to achieve. Moreover, this kind of tip is represented archaeologically, with shadows left by sinew wrapped tips appearing on artifacts from thousands of years ago. This sort of wrapping is also used on pin nocks like these:

The wrapping around the part right before the sides are cut in stops the center of the tip from splitting out. Obviously telling the 2 apart archaeologically is easy, since the shape of the wood differs. Both are old designs, and I may go with either one. i haven't fully decided. Any thoughts? votes? questions? Anyone still around after the long hiatus? I didn't mean to take so much time off, but I've been kinda busy.

Soon to come: the autopsy of a bow that exploded.

So, no pictures at the moment. I'm also sitting at home because the cops told everybody in the Boston area to not go anywhere.

Yesterday, I stopped by the Home Depot to look for boards. Some friends expressed interest in bow making this summer so we have to start checking for those perfect boards early on. I found one that was unusually dense. It didn't look much different (except it only have a few rings, mostly late wood) but it felt physically heavier.

Time to calculate S.G.! That's a measure of density relative to water. An sg of 1 is exactly the density of water. .5 is half the density of water, 2 is twice as dense as water. Most wood is around .3 for stuff like pine, .6 for stuff like oak, .8 is more like osage, and most things called 'ironwood' (many species are called this) are between .8 and 1.2. There's some variation within species, though.

To calculate sg, you need some measure of density. I can get cubic inches and pounds, and those should suffice. I first calculated the volume of the board. it's a 1x2x6, so .75"x1.5"x72"=81 cubic inches.

For weight, I used a small digital scale my wife uses for cooking. It can only go up to a few pounds, but the resolution is to half a gram. there are nearly 500 grams in a pound, so that's pretty sensitive. On pounds, the board came to 2lb 8.5oz (it rounds to the nearest tenth of a gram) or 2.53125 pounds.

this: http://www.calculator.org/property.aspx?name=specific+gravity can use lb/cu.in. so I divide the weight by the volume:

2.53125lb/81cu.in=0.03125. Plug that in, ask for sg, and I get: 0.86. That's insanely dense for oak. The other board came in at .70, still heavy for red oak, but not like the other. The 0.86 board is as dense as live oak, but it is clearly red oak. Live oak is diffuse porous like maple, red oak is ring porous. Plus it's very, very red.

I'm making this into a bend through the handle bow with long, stiff tips. Pretty standard stuff, really. Since my friend has been using my tillering stick, i can't get past the floor tiller stage. I now have 2 bows floor tillered and ready for the stick.

Back to bows! I took some time and floor tillered the ash stave. For those of you who skipped ahead to this, floor tillering is removing enough wood that you can bend the wood by putting one tip on the ground and pushing on the handle. When you have a slight wave in the wood of a stave, you have to follow it or you will get a hinge or a flat spot. Here's a shot down the limb:

see the hump? the belly wood was removed to follow that hump, making a concave area. If i just went straight across, there would be too much wood there, and it wouldn't bend. We can't have limb area loafing about, adding unneccesary mass, so I followed the shape. Later in tillering, I may leave a slight bit of extra wood under a knot.

The replacement tips on the walnut bow look like this:

I make my strings with a loop on one end and a knot on the other. This is the loop end. I removed that little barb on the belly side to keep the knot from slipping off the bow. Here's the knot side:

I haven't done the final sanding or oiling yet, but the shaping is pretty much done. Notice the maple glued on is considerably longer than the cherry was before. It may add weight, but I also removed a good amount of width from the tips. It probably weighs about the same? I don't know. It doesn't shoot any different.

Finally some work on the old school split ash stave. Now that it is floor tillered, I needed to get it ready for string tillering. Here is what the tips looked like:

Nock location marked, but not cut. Then some file work and viola:

Sorry it's blurry. I mentioned before I may not go with this type of nock, but there is still ample wood to shave down to whatever tip I feel like. It's over half an inch wide there, and slightly more thick.

Next for corner rounding. On boards, I tended to use the block plane, but staves don't have straight edges, so I used the pictured spokeshave:

Pay careful attention to knots

If I were to round the edge by that knot, it would cut into the wood around the knot. I don't know how well this will hold, but we'll find out eventually.

Knots in the middle of the limb aren't a problem:

I also did some work on the oak board I mentioned. Here's a blurry shot of the end:

Sorry it's blurry, but you can see how thick the growth rings are, and mostly late wood. This is why the board was soo dense. My wife's bow (photographed earlier) is almost half early wood, and a lot of the grain is 5-10 degrees off of parallel. It's straight, but not parallel. This board is almost perfectly straight, so here's hoping it doesn't break. It did seem to take a little set just from floor tillering, which is odd... I do plan on heat treating this, so I'll try to make it straight/ with slight reflex.

I'm going to make a couple strings using the previously described method and get my tillering stuff back from my friend's house. Most likely some tillering will happen next week. I want one of these to be done within a week or 2. Not being on lock down will cut into my spare time a little, though.

The photos at the top of this page (with all the staves) don't give a good sense of scale. The staves are between 70" and 86". Having a bunch over 7 feet gives me an idea:

A Japanese bow. These are super long (like 7') and asymmetrical. There's a whole different way they shoot, too. The arrow goes on the outside of the bow (right side for right handed shooters, not the left side like the european shooting style) and the string is held witha thumb. Instead of a finger tab, they use a specific kind of glove. The shooting stance is also different. They start up high, with the arrow parallel to the ground-ish:

Here's actually a great shot staged to show the draw and release process:

You'll notice they draw the bows crazy far back (partly why they need such long bows) and upon release the bow pivots around in the hand. If you have the death grip on the bow, it can't swing around. Notice this archer's death grip:

Those target bows have a crazy heavy stabilizer thing on the front, and non-death grip shooters let it pivot down. Also her elbow is too high, and her release is terrible. There's a reason for all of this, she's a singer, not an archer.

Since I found a bunch of these, here's a painful gif:

She accidentally dry fired the thing. You can see in slow motion how the string is shaking like crazy, since ALL of the energy in the bow had nowhere else to go. This bow is screaming in pain. Luckily most mass produced bows are built with some safety, and she was likely using a 20# bow or something else crazy light. At least her release was a 'pull back' and not a 'let go with a jerk'. If only the arrow was on the string...

Japanese bow may not happen. Some casual wikipedia reading got me this:

Height of archer--Arrow length--Suggested bow length

< 150 cm ---------< 85 cm ---------Sansun-zume (212 cm)

150–165 cm-------85–90 cm------Namisun (221 cm)

165–180 cm-------90–100 cm-----Nisun-nobi (227 cm)

180–195 cm-------100–105 cm---Yonsun-nobi (233 cm)

195–205 cm-------105–110 cm----Rokusun-nobi (239 cm)

205 cm+------------->110 cm--------Hassun-nobi (245 cm)

My height is 178.5 (yay biological anthropology class for informing me exactly how tall I am in CM. Also, I have a HUGE head for my body size. Unfortunately, anthro statistics class showed that there is NO correlation between brain size and GPA...) which lands me in a 227cm japanese bow. It's like 7'5.???" or so. Just slightly longer than my long staves. I'm gonna have to cut a couple inches off the staves to remove drying checks, too, so I'll be a few inches short. I could probably get away with it with a slightly wider bow/slightly lower weight.

I am in a dilemma here, though. On average, people's height and arm span are the same. My arm span is like 190cm (about 6'3"), despite my shorter than that height. If we assume they are figuring arm span = height, then I should have a 233cm japanese bow. That's like 7' 8". WAY longer than the staves. There are ways to extend stave length like attaching long stiff tips on the ends. If you have the bowyers bible book 2, look at the last page of the recurve chapter for a shot of what i'm talking about. Also this bow:

That guy tied them on because they are removable. I think he can take the thing apart in the middle and the tips and get it down to like 22" or something like that? Crazy. Anyhoo, i could glue and wrap tips on, and japanese bows seem to have stiff tips anyway:

There's also the point that I wouldn't be making an authentic one anyway, so I could change the design to suit my tastes (read: make it easier to produce) however I feel like.

Also there's the point that I still have 2 bows in progress and the black locust wood still needs a long time to dry so I may be getting ahead of myself... Stay tuned for that in, oh, say, 2014... I could always get an 8' board, too.

News! I took a look at a bow I was gonna post about autopsying a break to see what went wrong, but I can't figure out what went wrong (D'oh!). I may post about it, but I won't be able to point to exactly what happened. It doesn't help that I wasn't tillering it (wasn't my bow) so I can't tell if a bend problem was culprit, but I suspect it wasn't. I'll explain more later if I get pictures. Suffice it to say, sometimes they just break.

Instead, I'll give you a number of things to look for to spot a break before it starts:

1) improper grain on a board bow. Like I said many times before, you want uninterrupted wood fibers from tip to tip. You don't want lots of run off (though a few degrees of run off is almost inevitable), you don't want knots in board bows, and you don't want kinks/waves/islands/anything that looks anything other than straight and perfect.

2) improper treatment of knots on stave bows. Don't cut them flush to the back, always follow a ring. It's also not unheard of to leave a ring island of extra wood around the knot. You don't want them breaking.

3) Wood that is too dry. when a bow dries out, it will shoot faster and faster until it blows. Indoors with forced heat/ac usually ends up dryer than outdoors. Keep relative humidity comfortable for you and it will likely be comfy for the bow.

4) Sharp edges on the back. I said before to round the back edges of a bow. sharp edges create tension focused points where a splinter can lift, ending your bow's life.

5) Dents/scratches on the back. Same deal here, a weak point where a splinter can lift. This can be caused by not smoothing the back before tillering, or something whacking the back of the bow during storage. You don't want back flaws.

6) Overdrawing the bow. Don't do it. It could break. Don't ever draw past your planned maximum draw weight, and never past the maximum draw length for your design. Ever.

7) Dry firing the bow. Also don't do this.

8) Runaway compression fractures. The problems listed above usually result in a back breaking problem. A bow is still a bow until the back breaks, after all. The other failure point is the belly, which results in chrysals and set. However, a chrysal is a sign of an over stressed belly, causing a fracture and a weak point. This weak point can crush farther and farther unless you lighten it's load by removing wood everywhere else (it certainly isn't getting any stronger there). The compression fracture could travel deeper and deeper until there just isn't enough structural integrity for the bow to hold together at that spot, and it breaks.

9) Glue joint failures. Glue joints can be under incredible stress. glued tips, glued backs, glued splices in the handle, if any of them fail, they cause a weak spot. I had a bow that exploded because of a glue joint failure. It wasn't pretty.

10) Letting someone else use your bow. Guard your bow like your ATM pin number, don't go handing it to everybody. Many people won't know what they're doing and might overdraw your bow. It happens all the time. Some guy with a shorter draw of 26" will likely make his bows to draw 26". If some idiot with long arms like me picks it up and tries to draw back to his ear (31" or so for me) the thing will go kaboom. I make my bows with a little extra safety margin, so someone could probably go an inch past full draw without any issues, but certainly not 5" past. On more than one occasion I have seen someone using a borrowed bow straight up dry fire the thing. Full draw, no arrow. They just didn't think it was bad. After someone does this, immediately take the bow and check for back splinters or any other damage. Then kick that person in the nut sack.

I recommend checking for splinters now and then. When the bow is stung, run your hand up and down the back. You may feel a splinter lifting that would lay perfectly flat when the bow is unstrung. Also listen for an audible "tick" when drawing, a tell tale signal of wood coming apart.

If you find a splinter, all is not lost. I've hear you can wick thin superglue into the crack and clamp it to dry, but i've never successfully done this. I have, however, wrapped the e36m3 out of a lifting splinter and soaked the wrapping in super glue. That bow ended up dead and hanging on my wall, but it never broke at that splinter. It died from chrysals.

You may also canvas back, like easttowest did on his. Still waiting for photos on that one, btw ![]()

I should also mention broken strings and my broken nock incident, and how those don't equal dry firing. When a string breaks, it's usually slowly wearing out over time, getting weaker. When it finally goes, it only BARELY breaks. The energy that was bound for the arrow goes to the arrow, and 99% of the remaining energy that ends up pulling the string gets absorbed by the string. It's that last percent that breaks it. The limbs then shoot forward those few inches between strung and unstrung, hardly a dry fire. Still, check for belly damage.

The nock breaking off was the same way. It stood up to shots being fired until it weakened enough to barely break. When the crappy cherry nock finally gave way, the arrow still flew across the yard and into the target. It clearly took all the energy it was going to get, nock failure or not...

BTW I did break a string with my walnut bow lately. It seems like it's bound for that problem. I replaced it with a thicker string and so far nothing has broken, except my hope that this bow isn't cursed.

On an unrelated note, I mentioned earlier how dense wood like hickory can actually hold a sort of sharp edge, enough to slice into your hand if you aren't careful. It turns out particularly dense red oak can do exactly the same thing ![]() . Be careful!

. Be careful!

I have given too much emphasis on bow safety and bow protection, but a photograph I spotted recently has reminded me to mention arrow safety. An arrow, like a bow, flexes during shooting. Because everybody likes pics, here's one that shows an arrow flexing, including the nodes of vibrations (parts that don't move back and forth, for more info on 'modes of vibration' look up the overtone series. It's really interesting, especially if you're into music).

too stiff means not enough flex, too wimpy means too much flex. Both result in bad arrow flight, but there is an additional problem if this is taken too far. I've shot arrows spined at 61-65# out of a 20# bow. No problems except for arrow flight.

Do NOT click if you are squeamish

https://www.google.com/search?q=carbon+arrow+hand&client=firefox-a&hs=aWf&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=iGJ1UYy2NO354AOZgIGoCA&ved=0CDQQsAQ&biw=1920&bih=976#client=firefox-a&hs=CC0&rls=org.mozilla:en-US%3Aofficial&tbm=isch&sa=1&q=carbon+arrow+in+hand&oq=carbon+arrow+in+hand&gs_l=img.3..0.12863.13630.2.14211.7.7.0.0.0.3.149.677.4j3.7.0...0.0...1c.1.9.img.Dy2Hd49BmM8&bav=on.2,or.r_cp.r_qf.&bvm=bv.45512109,d.dmg&fp=66de61cc4a8868c2&biw=1920&bih=976

If the arrow spine isn't stiff enough, the arrow will bend wayy too far. What happens when something bends too far? It breaks. Do you remember how something bends? Here's a reminder:

A parabola. This is why bows are tapered to points at the tips, to even out the bend stress. An arrow isn't 'tillered' at all (some are, but i'm ignoring that) so all of the bend is right in the middle. Imagine that you're holding the string back, and a few inches into the shot, the middle of the arrow breaks. Where is the middle of the arrow mid-shot? That's right, just a few inches behind your bow hand. If you shoot off a shelf or your hand, this is still a dangerous thing to happen. The shelf guides the arrow, but remember it's broken. The shelf won't save your hand. The energy stored in the bow will jam the splintery end of the arrow straight through your bow hand, and you won't like the results. The pics I found were all carbon arrows. I've seen a pic claimed to be from shooting a 50# spined carbon arrow from a 150# longbow, and I've seen them claimed to be from compounds. Compounds are particularly violent shooters, hence the loud bang they make, but don't think longbows with wooden arrows are safe. A wooden arrow can lift a splinter like a bow's back, and that is a weak spot. If you shoot, the arrow flexes, and the splinter lifts more, creating a weaker point, and potentially a break. Keep your arrows in good order. Never shoot a damaged arrow, and certainly don't try to 'fix' one and shoot it again. It may not be as strong, and could just break again. Don't get hurt.

Rufledt wrote: News! I took a look at a bow I was gonna post about autopsying a break to see what went wrong, but I can't figure out what went wrong (D'oh!). ... (wasn't my bow)

Oh good - when I first read that I thought it was yours.

Yeah it wasn't my bow, but it was made with more care than mine. It's from the same walnut board as mine, backed with the same kind of hickory strip. I almost backed mine with that strip, I just by chance grabbed the other one. The bow that broke even had a MUCH better glue joint, and straighter grain on the backing strip. If there was a tiller problem, it would've crushed the walnut before the hickory would break. There are NO compression fractures that I saw whatsoever. My bow has a small compression fracture in one point, and no break. My friend is also fairly anal, and you better believe the back and back edges were silky smooth with no defects. It shouldn't have broken. it looks like it broke at a point where the hickory has straight grain. it also appears that the glue joint failed, but closer inspection showed that wasn't the case. The walnut was tearing itself apart, the tear reached the glue joint, and was diverted away. A proper joint is stronger than the wood itself, and hickory is stronger than most woods in tension. The tear, thus, traveled along the glue joint in the walnut. I know this because there is a thin layer of walnut stuck to the bottom of the hickory. It shouldn't have broken. He was only at 22" of draw or so. Even if one limb was more stressed than the other, it wouldn't be stressed to the point of a well tillered bow at 29" of draw. Can't figure it out. I doubt it was too dry, too. Hickory LOVES being too dry. Can't figure it out.

Edit: actually i just came up with an idea, but i'll have to inspect the bow again to be sure. Let's just say tension failure, but not in the way you might think...

Bendy handle bow update!

This bow started off much the same way as other board bows. A 1 x 2 x 6' was shaped with the center 2' full width, tapering to half inch tips. . The last 8" of the tips were then cut parallel 1/2", with an additional inch for the width to fade into the existing lines. The nock overlays were glued on, nocks were cut, back edges rounded, and the bow was floor tillered.

I skipped straight from floor tillering to strung bow, however:

For actual tillering, I told you guys a trick. Lay a straight edge (another board, usually) across the back of the bow and you can more easily visualize the shape of the bend. I can't do that here. The straight edge trick works because there is a flat reference point- the unbending back of the stiff handle section. This bow doesn't have extra thickness in the handle at all. The thing bends in the handle, so there is no straight reference point. How do you more easily visualize the tiller, you might ask. Here's a nifty trick.

Put the bow on the stick, bend it somewhat, and take a photo:

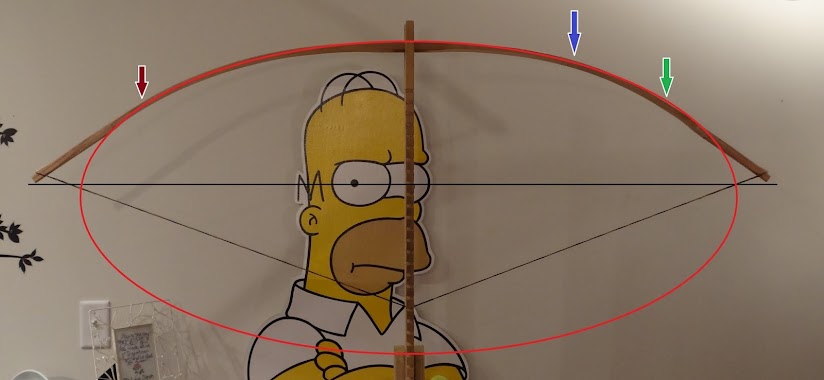

Here you can scrutinize a bit easier and without stressing the bow out by holding it at draw for too long. Open the photo in paint, and draw an ellipse. You can adjust the ellipse to make it fit, so you don't have to do it perfectly right away. Then, look where the ellipse aligns with the bow limb and where it does not:

There's a quick shot of what i'm talking about. You would do best to align the ellipse with the back of the bow, since the back is perfectly straight, or even better, align it with the neutral plane. This bow does get a bit thicker right in the middle (I want the middle to bend a little less than a perfect ellipse) and the ellipse method may be skewed by that slightly if you align with the belly.

Look where the arrow is pointing. That's clearly an area of the bow that bends too little compared to the other side. I'll have to get on that next time I get to working on it. to line the ellipse up with the tips, it has to be off center, indicating more bend happens in one side of the bow. Notice how elliptical tiller is the opposite of the parabola of a non tillered board. A parabola has all the bend in the middle, while the ellipse has more bend farther out. This is proper english long bow type tiller. You want the middle to bend slightly, but you don't want any set there at all. Set near the handle has a long lever (the rest of the limb) to amplify the bend, causing lots of tip deflection (set). you still want all of the bending parts of the limb to work, but you less than 100% work in the handle is fine. Less than 100% work by the tips means you have unneeded mass, resulting in hand shock, slow arrow speeds, and overall unhappiness.

More tillering. So at the point of the last post, I was partway through tillering a new, bend through the handle longbow. I got it to 40# @ 24", pretty nice and even, and heat treated it, bending it straight, as opposed to the 1.5" of set it had taken up to that point in tillering. I have noticed with red oak, the redder it is, the more set it will take. lighter colored red oak takes less set for some reason. Even density doesn't matter as much as the color. My wife's bow is less red than this, but less dense, and took less set. A bow I made before was very light colored, and extremely dense, and took extremely little set. The bow I claimed I was gonna back with canvas in a build post but haven't yet was even redder than this, was extremely overbuilt, and took way more set than it should've. The redness might be a sub-species thing. I don't know exactly.

With this bow, I heat treated the whole thing before I even to it to full draw. There's somewhat of a debate about whether or not this is a good idea/if it is required. Some say that once set is taken, some of the negative effects are irreversible. The wood cells are deformed, and though heating can straighten a limb, the cells will always be damaged. These people argue that you can take 2 identical bows. one you heat treat before full draw/full set, one you heat treat after shooting the bow in. The post-shot in heat treated bow will ultimately not benefit as much from the heating process as the one that was heat treated prior to taking set. i don't know if this is true. It's pretty hard to test. since each piece of wood is different, you would presumably need to make one bow one way, go back in time, and then make it the other way. The other option is to make a whole crapload of each, and run the numbers. I'm not gonna do that.

One method, the post shooting in one, I did to my wife's bow, and it seemed to work quite well for her. Her bow had been shot a good amount at 29" of draw, and after heat treating it has only been shot at 25" by my wife, so I can't report if the set reducing effect has stayed long term.

The during-tillering method that I'm using here has it's downsides, too. I got most of the way through tillering before doing this. Remember, the bending resistance goes up exponentially with thickness. a bow that pulls 50# @ 5" is far thicker than one that pulls 50# @ 10", but a bow that pulls 50# @ 24" is almost as thin as one that pulls 50# @ 29". After heat treating, though, this bow went from 40# @ 24" to 40# @ 20". Now there is much more wood to remove. Wood is removed from the belly. Heat treating happens on the belly. Do you see the problem? Heat treating improves the compression characteristics of the wood that then gets removed through the tillering process. Because of this, I may have to heat treat multiple times during the process to actually end up with any positive effect. This makes things take longer.

Right now i have tillered it back to 40# @ 24" just like before, and all of the darkened belly wood has been removed. However, set before heat treating was 1.25", and now is 5/8", so clearly the effect has not been eliminated. My plan is to tiller this bow now to 40# @ 28", do some shooting, and see if set gets any worse than 1.5". If it starts approaching that, I will heat treat again and do some retillering. at that point, I may likely retiller by width, not thickness. I may even do it by rounding the belly corners slightly, which would effectively narrow the belly without narrowing the back. I don't want this thing to break, after all.

Here's where I am at the moment:

See any tiller issues? That's at 21". I don't want to pull a bow to maximum weight when I'm going to leave it stressed long enough to take a ton of pictures. The problems at full draw weight would be the same only more extreme at full weight anyway, it may just cause set in places where the limbs are overstressed.

I'll give you a hint, there is a problem. At least one in each limb, though the problem in the left limb is MUCH more subtle.

Here's the shot with an ellipse drawn:

Notice the horizontal line drawn from tip to tip. That's so I know the tips line up on the x-axis of the photo. This is required because MS paint will only draw an ellipse on a horizontal x axis and vertical y axis, you can't angle it slightly. I took 4 pictures at ever so slightly different angles to make sure I got one straight enough. For that ellipse I lined up the middle with the middle of the handle, instead of the line of best fit, and tried my best to line the ellipse line itself with the neutral plane instead of the back.

You'll notice a couple discrepancies. First, the ellipse touches the back in the middle of the handle. This is intentional. The bow bends through the handle, but dead center you want slightly less then perfect elliptical bend. Any set dead center in the bow is the WORST possible place. Next you'll notice the limb on the right is all wonky, but it's not as easy to see why.

Near the tip, the bow is clearly bending too far past the ellipse, but the bow by the tip (green arrow) isn't bending too much. In fact, it's the opposite. The near tip wood isn't bending enough. The problem is closer to the handle (blue arrow). Problems with the limb manifest farther away from the handle. The blue arrow wood bends too much, so the rest of the limb is deflected too far. The green arrow wood isn't bending enough, so you see the ellipse above it curving back into the bow before the stiff tips begin. The ellipse by the handle doesn't look quite right either, but that's more because the the limb on the right is, in total, bending more than the limb on the left. If the handle were straight and unbending, it would be at a slight angle. Since this handle bends, there is no flatness at all.

The left limb actually looks pretty good, except the tip. The red arrow marks where the limb appears to stop bending. The problem here is that the bending limb fades into thick, narrow, stiff tips about 4" past that point. that 4" is therefor under stressed. Under stressed wood that is farther out on the limb is essentially dead weight. This causes hand shock, inefficiency, slower arrows, puts extra stress on the limbs, and a whole bunch of bad things. There is no good side to this.

It would seem that moving forward from this point is fairly straight forward. I need to shave down both outer limbs and get that wood to start working. This bow already has 8" long stiff tips, it doesn't need longer ones. The limb on the right is only bending slightly more in the middle of the limb, so a light shaving on the very inner limb would help balance the limb out. The left limb would be balanced if the outer limbs bend just slightly more, but then that whole limb would be slightly stiffer than the other limb. I'll have to remove a little wood from the whole limb in addition to the extra outer limb removal to get this thing back into balance. The bow will then likely only pull 40# @ 25", so I have some tillering to do, but you want to fix problems before continuing on. Failure to fix a weak spot can cause excessive, permanent set at that spot.

Don't think the ellipse solution is limited to bend through the handle bows. There are other solutions, I'll post about that at some point. The walnut/hickory bow has some tiller problems that popped up after the new tips were put on. The new tips aren't in exactly the same spot as the other ones, and aren't the same height, so the tiller changed slightly. Also it's still being shot in (no more than 100 arrows or so) and the tiller has been changing to be more round in the handle. This means the tips don't seem to bend as much, causing all of the problems I listed above about wood that isn't doing it's job near the handle. The hand shock on a 60# bow is uncomfortable, but the thing stores enough energy to still shoot a heavy arrow with lots of force. At my friend's house, we use a 3/4" thick plywood backing to prevent problems if we miss the small target box. So far, countless plywood impacts have not penetrated into the cardboard enough to cause the other side to bump out or show any signs of impact. Most of the impacts were from very light bows, 20-35# shooting very light carbon arrows. Light arrow means faster arrow but less kinetic energy taken from the bow. Not a recipe for deep impact.

This bow may have become inefficient, but it's still 60# @ 29.5". It therefor stores a great amount of energy, and has a LONG push stroke to transfer that energy to the arrow. A 25" draw bow braced at 5" has a 20" push stroke. This bow has a 24.5" push stroke. Since it's reflexed, the final few inches of push are still quite powerful. The arrows I was shooting were quite heavy, about double the weight of the carbons, and last weekend I missed the box. The arrow pushed out the other side. Whoops.

I'll post about how I plan on fixing the tiller, eliminating the hand shock, and lowering the weight a little bit at some point. Also maybe a few other methods for fletching without a fletching jig that may involve less work than the one I showed you before, if anyone is interested.

So that bow has 8" stiff tips. There are conflicting view points on why long, stiff tips result in fast bows. Notice how I never said they don't make for fast bows. Countless chronographing shows they do. No arguement there. Basically, there are 2 schools of thought here. One, championed by Tim Baker (who wrote most of the design and performance chapters in the bowyers bible books and is, in general, one of the most knowledgeable bow design guys of all time), believes the speed comes from reduced tip mass, increased energy storage from the favorable tip angles, and increased efficiency. The long tips reduce energy robbing limb vibration, making more energy available to the arrow. More energy, more efficiency.

The other though is held by a man named Dan Perry. Dan Perry is the guy that "perry reflexing" is named after. He is a very, VERY successful flight shooter (many records), and makes some of the fastest, farthest shooting all wood bows of all time. He believes there is an element of leverage going on. Basically, the longer the stiff tip, the more lever there is to amplify the speed of the limb tip. Take a basic short recurved bow, and a longbow with long skinny tips, and dry fire both (Don't actually do that) The longbow's tips should move much faster by this logic. Increased dry fire speed is more important in flight shooting than actual energy stored, because they shoot VERY light arrows very very quickly, and nobody cares about penetrating power.

I wish I could find the thread on paleoplanet where the 2 of them offer their distinct viewpoints, but that was a while ago and forum tolls have since run both of them off. Kinda sad, they were just being attacked by idiots constantly and decided they'd had enough of it and left a couple years ago.

Anyhoo, they both agree that these kinds of bows are very fast. You can see how someone could argue for either position if you look at the designs:

The bow i'm making here is MUCH less extreme than that. Mine has a bendy handle, and proportionately shorter stiff tips. This kind of design works great for short bows, since the favorable string angles (mentioned above) make for a force-draw curve with more stored energy than an elliptical tillered bow. I'm going to try to get the oak bow tillered to full draw today since I wound up with a day off.

Rufledt wrote: Anyhoo, they both agree that these kinds of bows are very fast. You can see how someone could argue for either position if you look at the designs:

I really like the idea of that. I don't know enough to explain why, but it looks like it will work really well.

It does work really well but its also really easy to screw up. With that design all of the bending portion of the limb is near the handle where set is extra problematic. Also, you have less total wood doing the bending since much of the outer limb is stiff and unbending. This means more bending has to happen with less wood and it can't take as much set. To get the same draw weight you have to make the bending portion of the limbs wider.

It's also easy to make the stiff outer limbs too heavy, which is the worst possible place for dead weight. Its hard to "tiller" accuately because you don't really want bend. Just the right amount of wood won't bend, but wayy too much wood still won't bend. Just remember you can go very narrow, but you need adequate thickness.

Also I got the oak bow to about 40# @ 28. Maybe mid 40's at my draw. Will post pics later after some shooting. I want it shot in and then ill check tiller again with an ellipse. There are bound to be problems so ill adjust them and hope it stays abut 40# at my draw length. If set gets too bad ill do another round of heat treating as well. We'll see.

Final tiller shots! So I shot the oak bow some today. Not as much as I'd like, but time kinda got away from me doing other stuff that was more vital, like school stuff. Anyhoo, the tiller may yet change some more but I won't be applying a finish very soon so I can always correct things if they go awry.

Here's a shot at 26"

At the end of tillering the bow was pulling 40# @ 28", and I shot it a bit at my 29.5" draw to no ill effects. The set comes in at 1 1/8" for one limb, 1 1/4" for the other, so about 1/8" difference between the 2 limbs. Nothing is ever perfect, especially when I'm making it. Do you see any problems with the tiller? When I look at it, I see all sorts of problems, and they come and go while i'm looking at them. I think something is wrong with my brain, because obviously the picture isn't moving. Here's a shot with the ellipse and tip-to-tip straight line drawn:

So overall not that bad, but not quite perfect. The photo size is reduced quite a bit from my computer to online hosting to posting it here, but you can still see the general idea here. One limb is bending slightly farther (just noticeable when the bow is braced, BTW). Also, like before, the wood approaching the stiff tips starts to stiffen before it should. Not a huge deal, but still not great. The handle being a little stiffer than full ellipse is extra noticable here as well, and the limb on the right i sslightly off of even. It looks like wood just out of the handle is too stiff, and then about halfway to the tip it might bent slightly too much. It's not a problem that will result in anything breaking, it just isn't perfect. I can deal with not perfect, and I can also fix it later should problems arise.

Set being between 1 and 1.25" is pretty good. 1.5" of set from a perfectly straight board is a good target to aim for. Less set means the wood may not be stressed to it's maximum efficiency, while too much means things went wrong somewhere, the belly wood is damaged, and the force/draw curve of the bow will suffer. Slightly too little set isn't a problem, though. The wood may be under stressed (meaning there is extra wood i.e. limb mass) but the slightly more favorable power curve should make up for it.

Tomorrow i'm going to my friend's house and we're gonna do some arrow work and maybe shoot this bow some more. It's important to shoot a bow in thoroughly before calling it done. My friend's first bow (I may have posted it here at some point or not, it's exactly the kind of board bow I described to all of you with a stiff handle and skinny tips) is well shot in. Close inspection shows some slight chrysaling on the limbs, but they are very short chrysals and they are evenly spaced throughout the bending portions of the limb, indicating even strain. They also haven't grown any bigger in the last few thousand shots, so it's a good bet that the tiller isn't going to change unless some idiot overdraws the thing.

In my list above on what can cause a break, you will notice I have added the following:

10- Letting someone else use your bow. Guard your bow like your ATM pin number, don't go handing it to everybody. Many people won't know what they're doing and might overdraw your bow. It happens all the time. Some guy with a shorter draw of 26" will likely make his bows to draw 26". If some idiot with long arms like me picks it up and tries to draw back to his ear (31" or so for me) the thing will go kaboom. I make my bows with a little extra safety margin, so someone could probably go an inch past full draw without any issues, but certainly not 5" past. On more than one occasion I have seen someone using a borrowed bow straight up dry fire the thing. Full draw, no arrow. They just didn't think it was bad.

They were told at the start of the target practice not to do it, but they forgot. Once was a friend of mine shooting an old bear bow (it was light and she's a short girl, so short draw length. No damage, but we got lucky) and the other was my friend's first bow being shot by his cousin. My friend almost had a heart attack but nothing broke. Again, lucky. After someone does this, immediately take the bow and check for back splinters or any other damage. Then kick that person in the nut sack.

A problem has arisen with my oak bow and has given me something to post about- how to build a better bow nock.

You can see I have a problem here:

The nock is gone. There are a couple reasons for this. Here's one:

Super light tips are beneficial in every way. Faster arrows, less hand shock, less stress on the bow. Unless something breaks. Narrowing the tips reduced the glue joint surface area, which weakens the joint. If you look carefully, you'll notice most of the wood for that particular glue joint is porous early wood. Bad stuff. The glue joint didn't fail, the early wood pulled apart. Crap. It's clear I need a better way to do this. One possibility is to cut the nock in at an angle. The nature of this break pretty much required me to do this or to shorten the bow.

The bow's back is on top, and you'll see an angle there. Here I drew some lines on:

Lime green is the line of the bow's back, black is where I planed for the nock. Take a look at a strung long bow's tip:

See the angle the string is pulling on the nock? It's creating a lot of shearing force on the glue joint. As the bow is drawn, the angle changes, and when the bow is at full draw, the string is pretty much only pulling down on the bow tip, not sideways on the nock. Even if the glued on wood is glued on like the walnut bow I made where the overlay was big and the nock cut into but not through the wood, there can be problems (like I had!). The shearing forces, then, are along the grain of the wood, and can cause the wood to split. Gluing on at an angle means that at brace height, the string angle isn't pulling as sideways on the glue joint or wood grain, but pushing down on it.

This wasn't a glue joint failure, but there are ways of making better glue joints, too. Here's the piece I'm gluing on:

You'll notice it's all screwy looking. I planed it perfectly flat with a hand plane, and then scraped a coping saw blade sideways along the grain to create many small scores in the wood. This increases glue surface area and can make for a better glue joint. Do it to both pieces you are gluing. For this bow, i glued the nock overlays on with superglue. It worked for the walnut-hickory joint on the walnut bow, and that should be under far more stress. I figured it works well here and the extra power of the titebond glue wasn't necessary. For handles and backings i still suggest titebond, but this superglue sets very quickly and reaches full strength much faster than titebond. Again, it's not as strong, but it's still stronger than the wood around it.

There are other ways to strengthen a nock overlay, and I'll be doing that after the glue dries and I shape the nock. It uses an old trick seen many times in the pages of this thread. More superglue. Stay tuned.

Questions for the audience:

Anybody still out there except tuna? I'm happy to keep going even if only tuna is reading, I think this is fun, I'm just curious.

Anybody out there making a bow?

Fromeasttowest- Got any more photos of that bow you made?

Anything anybody wants to see more specifically? I'm going to get to the oak recurve and the ash stave bow right after I get this oak one finished and get the walnut tiller fixed and finished. I probably won't post much about that except the tiller fixing with a new ellipse trick for stiff handled bows.

Anyone interested in a quick and cheap atlatl build? I could probably do that all in one post, there really isn't anything to those.

Welcome to the thread!

Does anybody here watch golf? I don't personally, but I know people must watch it or it wouldn't be on TV. Personally, I find it insanely boring. I imagine it's more interesting if you actually play golf and have an interest in the sort in general. The reason I bring this up is because my wife and I were watching archery on youtube. Yes, I typed that right. My wife was watching archery competitions on youtube. I would assume it's somewhat like golf. If you have no interest in archery, it must me absolutely mind numbing. I'm not talking videos like this one:

Byron Ferguson shoots an asprin out of the air at the end

I'm talking videos like this:

2012 indoor compound nationals bronze match (women)

I love archery, and I find that fairly mind numbing, but I'd be lying if I said I didn't watch to the end and try to find the gold match after. Is that what golf lovers feel when watching golf? Are they all like "this is crazy boring, but I can't turn away, who wins?!"

This is more intersting:

Korean celebrity olimpics (the gifs from above are from this)

And this

Found this one, too

Surprizingly no gifs from this video...

(Here's the whole 2013 korean celebrity olimpics if interested)

Though, to be honest, archery isn't why those videos are interesting. The commentators are like soccer announcers, WAY more excited than they should be. My wife (she speaks korean) says all of the noise is coming from 2 of them, while the 2 quieter ones are actually archers. The 'competitors' are all celebrities somehow, and they do this olympic thing every year. Who here wants to see the cast of big bang theory try to do this? I'd watch it. Should be entertaining. Or how about a Leno vs. Conan vs. Kimmel vs. Fallon ski jumping?

And for some reason women's archery videos are wayyy easier to find than the mens ones... hmmm...

Yeah no actual bow making this post. I may have to postpone further nock making until tomorrow.

So I lied, I did do some late night work. Here's how I shaped the new piece:

You can still see the angled glue line. Where the arrow nocks isn't exactly where it was before, but it's close enough. I hope it doesn't mess with the tiller any. It should be an insignificant change. As promised, I also strengthened it. To do this will require some super glue and some thread. I used artificial sinew. The traditional way to do this is hide glue and actual sinew, or just wet sinew. Wrap stuff, let it dry, and the sinew will contract.

To start, I laid down a small line of glue and put the artificial sinew in it.

Leave an extra 6" or so of thread hanging off one side. Now, wrap around the tip tightly a few times:

Cut the thread leaving a few inches of extra thread, and tie the 2 ends together.

Cut off the excess, put a drop a super glue on there, and you're done. I also rubbed a little super glue all the way around the wrap to hold it secure. Now a split cant lift, and the nock can't slide inward if the glue joint fails. If it tried, the wrap would tighten.

I also went ahead and did the other tip as well

Make sure the knot is on the bottom, not the side like the first one I did. I think the string loops might rub against the knot on the side. I'll see if it ends up being an actual problem. There are other ways to strengthen tips as well. I saw a bow with a very tiny hole drilled and doweled.

I don't trust my ability to do something that exact. The maker of that bow makes some really awesome unique bows out of wood i wouldn't dare use. He knows what he's doing WAY more than me.

Whew that was the longest hiatus since I started writing this thread! A lot has happened, and almost none of it archery related. There was a death in the family, specifically my wife's family, so we have been in South Korea. We didn't have much time to spend roaming the city, since it was mainly a family oriented trip, but this is the only archery related thing we did:

At a kind of museum thing that was a couple reconstructed old houses, there was a bow on the wall in one building, as well as a quiver, and I took a picture of it. That's it. At least this place knew enough to keep it unstrung. You'll see the massive reflex and recurves at the ends. Unlike other recurved horn/sinew based bows, these are fairly lightly built. This is part of why they have such incredible speeds. High energy storage due to the massive reflex and recurves, low limb mass. It's also short, which generally means less moving mass when the bow is fired. The fastest distance oriented ones were thought to be capable of shooting a lightweight flight arrow nearly half a mile. Pretty incredible. They are insanely tough to maintain, though. They have to be constantly balanced with heat and pressure, and they can reverse when shooting, causing them to break. Bad news bears. Also, at lower weights, they don't out-shoot wooden stick bows, since extra material is needed in the limbs to keep them from twisting when returning to brace height. Still pretty sweet, though.

It'll probably be too busy around here to do any serious bow work for a while. We're moving in a month or so, plus I have a thesis to finish up. Far too much to do and not enough time to do it in. After the move, it'll be a while to settle in, but rest assured, I will get back to bow making. Also if you have any questions, feel free to post them or PM me, i'll still be around and might even post progress now and then if I get a chance to work on anything.

I did recently get a fletching jig from my uncle, and I'll be sure to post a how-to about that. It is capable of getting far more consistent fletchings, without the need for any wrapping. It's also far less work. Good news for all.

Rufledt wrote: At least this place knew enough to keep it unstrung.

glad to see an update. I was thinking about this thread - and this very topic - just the other day. I made the mistake of watching Immortals on netflix. Part of the film involves a quest for a bow. When it is found, it has been stored, strung, for many years.

I just sighed and shook my head. ![]()

You'll need to log in to post.