The Chesapeake & Ohio was home to the greatest luxury train that never was: The Chessie.

In 1942, the visionary Robert R. Young gained a controlling interest in the Alleghany Corporation, the holding company previously controlled by the Van Sweringen Brothers, which owned the Hocking Valley Railroad, Nickel Plate Line, Chesapeake & Ohio, Pere Marquette, and Erie Railroad. Young immediately began challenging long-standing conventions and traditions, trying to make his railroads operate more efficiently. He knew that they had been important to America's development and the war effort in WWII and sought to capitalize on that moving forward. Symbolic of this mindset, one of Young's earliest actions was to instate a new C&O logo, which said "For Progress".

Having seen the rise in passenger ridership during WWII, as well as the ongoing passenger train arms race between Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central, Young decided that the C&O should launch a new luxury train. This raised eyebrows in the railroad industry, as the C&O was not a line that offered much in the way of passenger service. They offered cursory short-distance trains and only had 4 named passenger trains: George Washington, Fast Flying Virginian, Resort Special and Sportsman. This new train was to be named Chessie after the long-standing mascot of the C&O's passenger department. For years the C&O had used Chessie The Kitten on their advertising, proclaiming you would "Sleep Like A Kitten" on their trains.

Announced in 1944, the Chessie would operate in daylight between Washington D.C. and Cincinatti in daylight, and would have a connection to Newport News and Norfolk at Charlottesville and a connection to Louisville at Ashland, Kentucky. The train would be entirely composed of new Budd-built lightweight equipment. While a standard passenger coach of the era would seat either 44 or 60 passengers, C&O planned for theirs to only seat 36 per car, to give the passengers unprecedented room to relax. A year before CB&Q unveiled the first dome car, Young planned for the Chessie to have dome cars. There was to be a large fish tank on at least one of the cars. The twin-unit dining car would have a section showing first-run movies. The 48-car order was placed with Budd in 1944, and cost $6.1 million dollars.

While diesels were starting to arrive on the scene in force, the C&O was primarily a coal-hauling railroad and was loath to stray from coal power. Also, the C&O engineering department was concerned that oil reserves would be depleted in 20-30 years. But the C&O wanted their train to look fully innovative and so they paid for the development and construction of 3 experimental coal-fired turbine electrics by Baldwin and Westinghouse at the cost of $1.6 million. The M-1, as they were classed, were the largest single-unit locomotives constructed and used a 6000hp Westinghouse steam turbine turning 4 generators to make 4960hp at the wheels. With less moving parts, the M-1 was theoretically more reliable and was believed to be able to make the entire trip without servicing. They had an 11-position throttle and an early test run was made with the throttle at notch 7, cruising at 75mph. The engineer was reported to have said that he was dissatisfied with the 75mph track limit and he "sure would like to pull the throttle back to 11!"

The connecting service trains weren't neglected either. Although they would not be pulled by big M-1 turbines, the C&O sent 5 of their older F-19 Pacifics through the shop and "rebuilt" them into L-1 Hudsons. In reality, they were essentially all new engines, really only reusing the firebox and outer boiler shell. They received an all-new cast frame with integrated cylinders, roller bearings on all axles and rods, multiple bearing crossheads, precision balancing on the 75" drive wheels, a new more efficient Type E superheater, more efficient Worthington feedwater heaters in place of the old Elescos, a high-speed Franklin booster in the trailing truck, and experimental Franklin oscillating cam rotary poppet valve gear. They were also streamlined in an orange-ish and stainless-steel scheme, except for a single engine, #494, which was left unstreamlined. Engineers reported the L-1s to be very fast and very powerful and smooth-riding, with an anecdote of one hitting 95mph with 6 heavyweight cars without the engineer realizing the speed.

In 1948, the equipment order was complete and the Chessie made a single test run. And then, nothing more. What happened to arguably the most ambitious, most luxurious train ever constructed? The decision to create the Chessie had been influenced by 1944's record-setting 6.7 million passengers. But since then, ridership had fallen to under half in 1948, at 3 million. Also, the Baltimore & Ohio's Cincinnatian was running an identical route and was much cheaper to operate than the Chessie would be, but was failing to turn a profit due to the light population density along the route.

The C&O instead broke up the equipment. The 3 dome coach cars went to the B&O. The 3 dome observation cars were sold to the Denver & Rio Grande Western. Many of the coach cars were sold to Atlantic Coast Line, as well as the dining cars, and Seaboard Air Line bought a number of cars as well. Several passenger cars went south of the border to Argentina, including the car with the large fish tank. And the handful of cars that the C&O did keep went out to the Pere Marquette Division (in '45, Pere Marquette Railroad had been absorbed fully into the C&O and ceased to exist) to be used on the new pair of trains named Pere Marquette. The M-1 turbines, deprived of their reason for existence, were put into use between Clifton Forge and Charlottesville but, like all attempts at steam turbines, proved to be expensive to operate and hideously unreliable and were all cut up after only 2 years. The L-1 Hudsons were repainted to yellow, earning them the unfortunate nickname of Yellowbellies by crews, and ran in regular passenger service, but two were retired and scrapped in 1953, and then another two, including the unstreamlined #494, were retired and scrapped in 1955. Only #490 survived, preserved at the B&O Railroad Museum. Interestingly, there are no accounts of the rotary poppet valve gears being as troublesome as they were reported to be on other railroads.

Robert R. Young would end up moving on from the C&O. He launched a proxy war that gave him control of New York Central in 1954 and brought in Alfred Perlmann to act as president. Young and Perlmann had dreams of merging the NYC with a western line, like Milwaukee Road or Santa Fe or Union Pacific or the Hill Lines, to make a true transcontinental railroad. But they kept running afoul of anti-trust laws and western lines weren't interested in the financially-ailing NYC. Young, who had long fought with clinical depression, committed suicide in 1958, believed to have been caused by stress from the NYC's ruinous state that he was not fully aware of until taking control, as well as NYC stock tanking in '58 and costing many of his friends and family, who had invested in the Central, a small fortune.

In reply to NickD :

Wow, that's a really interesting story. TIL. Those were some handsome locomotives.

In reply to Duke :

It was basically the Edsel of the rails. Or the Edsel was the Chessie of the roads. There was such a long time between the decision to make it and the train actually being introduced that it no longer made sense by the time it came out.

Those Hudsons were definitely interesting. I like that they were called a "rebuild" but were basically a brand-new engine. I'm guessing that it was the C&O's way of getting around the War Production Board saying no all-new locomotive construction without their approval (and they were only approving existing designs that could be dual-usage). Reading did the same thing when rebuilding their I10sa 2-8-0s to T1 4-8-4s. They essentially tossed everything out and built an all-new engine except for a few parts.

In reply to NickD :

I've seen existing cabins "remodeled" in flood-prone areas by a similar method: build a new house around the outside, then remove the existing bits through a door when you're done.

Robert R Young's famous advertising line was "A Hog Can Cross The Country Without Changing Trains - But YOU Can't."

Under Young's anointed one, Alfred Perlmann, the NYC began a number of run-through trains with CB&Q, Santa Fe and Rock Island at both Chicago and Streator, Illinois and the MoPac and Southern Pacific/Cotton Belt at East St. Louis. I'm curious which western lines Young tried to get a merger with, since there is no mention. The only ones with a direct interchange with the NYC before Young's suicide were the Santa Fe at Illinois via direct connection or at Streator via the Kankakee Belt Route, and Southern Pacific/St. Louis Southwestern at East St. Louis. Union Pacific did not have direct access to Chicago or St. Louis at the time, although they were trying to via the Rock Island, and the Hill Lines (Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Spokane Portland) wouldn't get their own access until they merged and included CB&Q to form Burlington Northern. The Alleghany Company, the holding company for C&O, also had a large chunk of Missouri Pacific stock, so perhaps Young planned to use his influence there.

A rare action photo of one of the C&O M-1 turbines in regular service. Those clerestory roof passenger cars its towing are a far cry from the lightweight stainless steel Budds it was designed to haul. Part of the issue with the M-1 was that the coal bunker was to the front of the locomotive (the tender only carried water) and the coal dust would short out the front traction motors, while water dripping from the rear mounted boiler would short out the rear traction motors.

#500 at the 1949 Chicago Railroad Fair. Pretty strange that the C&O would choose to display them at the fair, since they were a lame duck engine constructed for a train that never ran, and at this point already had a reputation for being troublesome.

A color photo of the #500 at the Chicago Fair. Even during the M-1's early testing in 1947, it had been plagued with issues that never seemed to be resolved. If the Chessie ever had gotten off the ground, the M-1s probably would have been yanked off in short order, either for a J-3 Greenbrier or maybe EMD E-7s

oof, that last photo. what a depressing shot.

and you're right - that final image of the M-1 really made me look twice. before, i had a bit a sense of the size but something about that shot, with people for scale, makes it look absolutely titanic.

In reply to ScottyB :

The M-1 was just over 154 feet in total length and 388 tons. They were one big SOB

In reply to LS_BC8 :

The M-1 was designed for passenger usage and is confirmed to have hit 75mph at around 70% throttle in testing and had a theoretical top speed of 100mph. The Jawn Henry was a freight unit and anything I can find on it was that it was most efficient at low speed. A Norfolk & Western Class A 2-6-6-4 would actually outperform it above 12mph, on pulling power and fuel consumption. It was also less powerful than the M-1, at 4000hp, and was even larger at 161 feet.

One of the more heartwarming stories of passenger trains was that of the Delaware & Hudson's Laurentian (Train #38 Northbound, Train #39 Southbound). The Laurentian was inaugurated in 1923 as the D&H's flagship train, offering same-day daytime service between New York City and Montreal, Quebec by way of the D&H's picturesque routing along Lake Champlain above Albany and cutting through the Adirondack Mountains, making stops at Albany, Colonie, Whitehall, Mechanicville, Watervliet, Cohoes, Saratoga Springs and Troy, amongst others. Since the D&H did not have access to Grand Central Terminal, the train actually left New York City behind New York Central electric power up to Croton-Harmon, then used NYC steam power (later diesel) power to haul it up to Albany-Rensselaer where it switched over to D&H power to haul it the rest of the way. This resulted in the odd appearance of D&H passenger cars behind NYC power, and Canadian Pacific engines were often used to spot the D&H cars at Montreal as well.

The D&H also offered a nighttime version of the train, called the Montreal Limited, which took a very similar routing but took an express route from New York City, to Croton-Harmon, to Troy, where it switched to D&H territory, then crossing the Hudson, straight through Saratoga without stopping, and made its next stop at the final U.S. city on the route, Rouses Point. The Laurentian and the Montreal Limited were the only two named passenger trains that the D&H operated and made the 10 hour, 375 mile round trip daily. At its inception, the trains consisted of Pullman heavyweight cars pulled by either a D&H P-Class 4-6-2 Pacific or a K-class 4-8-4 Northern. Either engine was distinctly D&H, with their unusual shrouded front pilot, recessed headlamp, elephant ear smoke deflectors and wide Wooten fireboxes.

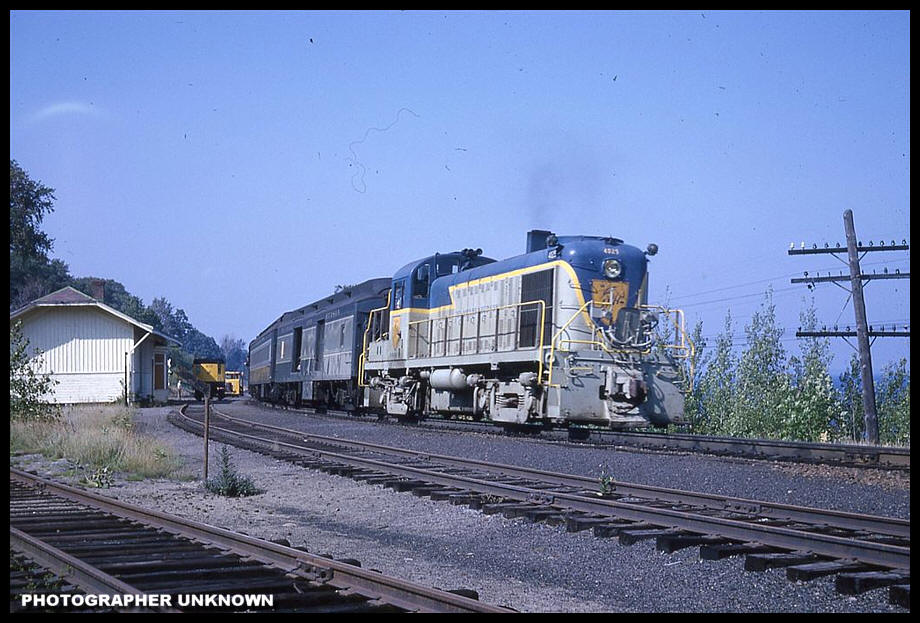

The Laurentian operated essentially unchanged for 30 years, until the D&H dieselized in '53. At this point the steam engines were replaced by Alco RS-2s. Despite dieselizing relatively early, the D&H skipped completely over carbody Alco PAs and FAs, and ignored EMD, Baldwin and Fairbanks-Morse offerings entirely (the first non-Alco diesels wouldn't arrive on the property until into the '70s). In 1958, the demolition of Union Station in Troy, NY eliminated the stop at Troy, instead replacing it with a stop in Plattsburgh. Later Alco purchases, like RS-32s, also found their way onto the head end of the train through the '60s.

By 1964, the D&H was feeling the financial squeeze of every northeastern railroad, and like every North American railroad, it was looking to discontinue long-unprofitable passenger service, or at least cut back as much as the government would allow. The D&H, which had been disinterested in passenger operations since WWII, began making rumblings that the Laurentian would be discontinued to cut costs. When word of this got out, there was a public outcry amongst upstate NY residents and the D&H decided to keep the train alive. Now, while most lines would have just trimmed the train back and made it a cursory operation, the D&H's new president, Frederic Dumaine, was a bit of a railfan, and instead decided to give the Laurentian and Montreal Limited an upgrade.

The Denver & Rio Grande Western was selling off Pullman lightweight passenger equipment as it trimmed down it's passenger operations, and the D&H grabbed them up and repainted them in D&H's blue and yellow.

But the really big news was that the D&H purchased the last 4 existing Alco PAs. Built as Santa Fe #54, #59, #60 and #62, ATSF was the last Class 1 still operating Alco PAs at that point in time, using them on the Chief, everyone else having retired the beautiful but troublesome Alco passenger units. ATSF had attempted an EMD repower but found it too expensive and had decided to trade them in on new GE U28CG and U30CG, as well as relying on EMD E and F-units that they still had in inventory. Delaware & Hudson purchased the traded-in quartet from GE, cleaned them up and repainted them in a version of the Santa Fe Warbonnet livery but with D&H blue and yellow, earning the nickname Bluebonnet, renumbered them to #16, #17, #18 and #19, and put them in service hauling the Laurentian and Montreal Limited. Suddenly the two trains went from those obscure pair of trains operated in conjunction with NYC, to the snappiest-looking passenger train in the US.

In 1968, there was a slight change to operations, as New York Central became Penn Central. This had no major effect, other than I'm sure the first or last segment (depending on direction) was probably late a bit more, as Penn Central's operations were disastrously disorganized. Also, at the same time, the D&H and the Erie-Lackawanna were taken over by N&W under court order, although things continued as usual. Then, in 1971, Amtrak took over passenger operations for almost all US railroads, which had long been trying to dump passenger service for a long time. The Laurentian made its last run on April 30th, 1971 and the . With the Alco PAs out of work, D&H saw no reason to hold onto all 4, and traded in #17 and #19 to GE for new U-boats.

Despite how grim things looked, they were about to get better. When Hurricane Agnes wiped out much of the Erie-Lackawanna, the court order placing D&H under Norfolk & Western control was also wiped out, and new management was installed. New president Carl B. Sterzing was a bona fide railfan and he immediately reacquired the #17 and #19 from GE and set to getting the Alcos fired back up. They managed to get three of the PAs fired up and were running them about in fantrip service. Then Sterzing convinced NY state that there needed to be service on the D&H line between Albany and Montreal and the state convinced Amtrak to essentially revive the Laurentian. Since Amtrak was still an absolute mess, Sterzing offered to run the Amtrak's new train, to be called the Adirondack, using D&H equipment. Sterzing, who must have been a real silver-tongued devil, also talked the state into giving the D&H $3.2 million to upgrade the tracks, recondition equipment and reopen several shuttered stations.

The reasonable move for motive power would have been to purchase new power along the lines of an EMD SDP40F or a GE U34CH, but that wasn't Sterzing's style. He wanted to put the 4 Alco PAs back in regular usage. But the now 25-year old PA-1s, which had never been the most reliable when new, were starting to show their age, and the 244 engines were difficult to source parts for, especially now that Alco had gone out of business. So all 4 of them were shipped to Morrison-Knudsen and were overhauled into what was called a PA-4u. The biggest change was having their 2000hp V16 244s removed and replaced with much newer and more reliable 2400hp V12 251C engines.

On August 5, 1974, the Adirondack, looking to all the world like the 1968 Laurentian, made its first run, that according to the New York Times, “was greeted by bands, bunting, flag-waving crowds and orating politicians”. The VIPs included then New York State Transportation Commissioner Raymond T. Schuler and Governor Malcolm Wilson, who made a pitch for a $250 million state rail bond. The bond passed later that year, triggering a major upgrade of the New York-Albany-Niagara Falls “Empire Corridor”. Despite being an Amtrak train, the D&H ran the Adirondack as if it were its own train, down to the tablecloths, menus, and chinaware which displayed the railroad’s logo and blue and yellow corporate colors. It provided the engine crews, conductors, dining car staff and coach hostesses. In addition to coaches, the D&H offered dining and dome cars first leased from Canadian Pacific and then later provided by Amtrak. Much like the original Laurentian there was a changeover at Albany, where D&H handed off operations to Amtrak to take it the rest of the way into GCT.

The Adirondack continued operating in this configuration until 1977, at which point Amtrak finally had gotten its legs under it and was ready to take over operation. There is also said to have been some disgruntlement by Amtrak and the government over the fact that the D&H had essentially commandeered the train. Amtrak taking over the train did smooth out operations as well, since now the train stayed in the hands of a single railroad the whole trip, instead of a handover at Albany. The Adirondack, and in essence the spirit of the Laurentian, is still in operation to this day, some 46 years later, although its definitely a lot less stylish, with Amfleets and Genesises.

Without the Adirondack to pull, the PA-4us lost their purpose on the D&H. They hauled some railfan excursions, along with the last two Baldwin RF-16s that Sterzing had purchased, and then were leased to the Massachusettes Bay Transportation Authority from '77-'78. When Sterzing was replaced with Kent Shoemaker in 1988, Shoemaker was less than enamored with D&H's rolling railroad museum and sold off the Alcos to Mexico, where they were almost immediately destroyed by derailments and severe neglect. Two are now on cosmetic display in Mexico, one in primer and one is SP Daylight colors, while two were repatriated and one is being repainted to Santa Fe colors and the other is being restored as a Nickel Plate unit, sadly wiping out the D&H history.

NickD said:This angle really clues you in to just how massive the M-1 was.

Was the chassis articulated anywhere in the middle, or just the trucks? I'm not seeing any obvious bendy bits.

In reply to Duke :

Just the trucks, and not all of them. They were essentially two Pacifics hooked together, with a 2-axle unpowered truck, a 3-axle powered truck and then a single-axle unpowered truck, then another 2-axle powered truck, another 3-axle powered truck and another single-axle unpowered truck. The unpowered trucks could rotate/swivel, the powered trucks were rigid-mounted.

I friend of my dad's loaned me an older documentary on the Norfolk & Western J series, especially the only surviving example: #611.

I'm not that much of a "steam guy", but man, what a piece of machinery. We may end up with a hypothetical J powered excursion train on our layout.

I'm really enjoying this thread, but I'm going to tell on myself. WIthout having been exposed to the Chessie history, I found their modern logo inscrutable. Is that an alien retching? Is it a winged helmet with a headlight facing the wrong way? I ended up having to Google it to get the back story, and that was only maybe two months ago.

You'll need to log in to post.