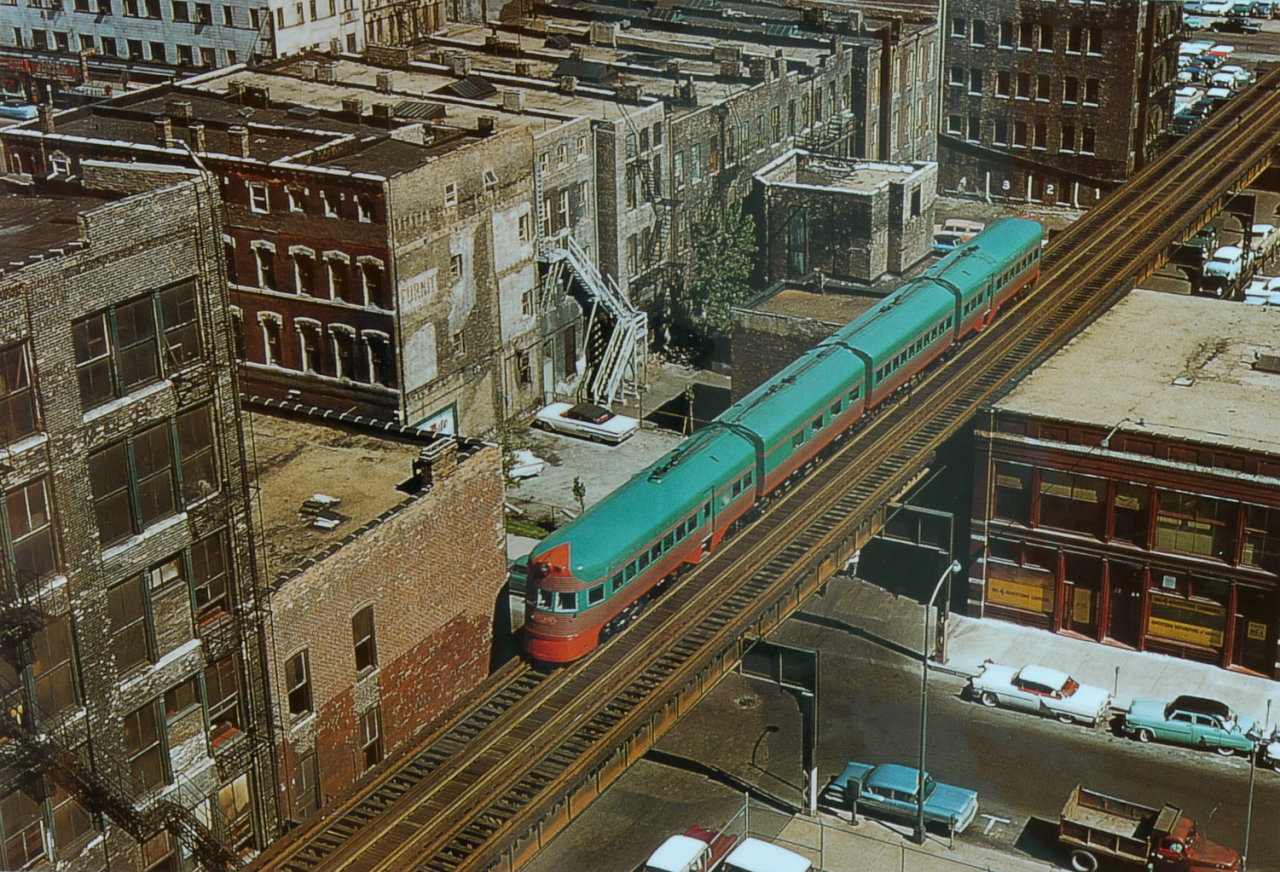

Those Electroliners weren't just a pretty face either, they were some of the most advanced interurban equipment in the US when they were constructed in 1941. The Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee was facing bankruptcy in 1940. Interurban lines were folding up left and right, the Great Depression had mauled their finances, their equipment all dated back to the early '20s or older, and they faced literally side-by-side competition between Chicago and Milwaukee from the Milwaukee Road and the Chicago & North Western. But the North Shore did offer convenience in the fact that it's equipment also ran on the Chicago elevated line with multiple stops in the city, unlike the MILW and the C&NW. Labor unions were worried about the bankruptcy and lost jobs, so management proposed buying newer high-speed equipment if the employees would take a slight wage cut. The unions agreed and so the North Shore began developing new equipment with the St. Louis Car Company, who was also on the verge of going out of business from the loss of interurban companies purchasing equipment.

They had a number of difficult requirements that it had to meet:

- It had to be compatible with the sharp curves, narrow clearances and high platforms on the Chicago Loop and L lines

- It had to be able to attain high speeds on the North Shore's main line so that it could run comparable times to C&NW and MILW

- It had to be able to run on Milwaukee streets

Two of the units were constructed as articulated 4-unit sets, with a streamlined control car on each end that was based off the CB&Q Zephyrs. The control cars had a truck under the front end, and then they shared trucks under the vestibule of each car. This reduced the yawing sensation on curves and gave them a much smoother ride at high speed. To accommodate both the L's high platforms and the North Shore's regular platforms, they had a trap door over the steps on the end. While on the Loop or L line, you left the trap door down and passengers could walk straight across to the platform, everywhere else you lifted the trap door and the passengers went down a set of steps to disembark. They also had both pantograph power pick up and third-rail shoes.

Each trainset could hold a maximum of 146 passengers; each power car doubled as a luxury coach and could hold 40 passengers each. One of the power cars was also split with a smoking lounge that that held 10 individuals, one of the center cars also held 40, and the other center car was configured as a luxury lounge that featured an occupancy of 26. The Electroliners were much better appointed than your standard interurban car, in order to draw more riders, and were also all air-conditioned, which was a first for interurban cars, pantographs for the street running and then 3rd-rail for the L and other areas that weren't publicly accessible.

The North Shore put them in service, but despite their streamlined appearance they were limited to 80mph, which was the North Shore's maximum track speed. Despite that, passengers said that on runs where the motorman had the cab door open, they could see the speedometer hanging at 90mph. And on one of the early tests, North Shore management allowed a motorman to enable full field shunt on the electric motors and they hit 110mph. At that speed though, the set was well through the grade crossings by the time the crossing gates started to lower, so this was only officially done the one time.

The Electroliners were an instant hit and reversed the North Shore's fortunes, at least for a while. Earnings improved, and the new equipment allowed them to take some of the older cars out of service to overhaul and refreshen them. Eventually though, highways and automobiles began eroding the North Shore's profitablity, and in 1963, the North Shore cashed it in. Both Electroliners were still in good condition though, so they were sold to Philadelphia Suburban Transportation Company, also known as the Red Arrow Lines, where they received a new maroon, dark blue and white livery and were called Liberty Liners. When SEPTA was formed in '65, the Red Arrow Lines were incorporated into it, and so the Liberty Liners were transferred to SEPTA. Finally, in 1978, SEPTA retired them, with one set being purchased by IRM, returned to Electroliner colors, and operated into the '90s before motor failures knocked it out of service, and the other was sold to the Rockhill Trolley Museum in Orbisonia, PA and remains operational and unrestored in Liberty Liner colors.