Passengers disembark from a South Shore interurban train at Michigan City, IN on June 14th, 1980. Car #25 was built in 1927 by Pullman Standard, so it was getting pretty long in the tooth at that point.

Passengers disembark from a South Shore interurban train at Michigan City, IN on June 14th, 1980. Car #25 was built in 1927 by Pullman Standard, so it was getting pretty long in the tooth at that point.

Turning onto 11th Street in Michigan City. This bit of street-running was still active, and still using interurban cars, although more modern Nippon-Sharyo cars, as recently as this year. Sadly, the line is being relocated, for both speed and safety reasons.

The Chicago, South Shore & South Bend remains as the last stand of the old interurban lines. The Washington & Old Dominion, Pacific Electric, Illinois Terminal, the Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee, the Bamberger Railway, all gone, most of them 70 or so years in the grave. It is certainly the last of the Insull Lines, which included the South Shore, the North Shore, the Gary Railroad, and the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin, all owned by Samuel Insull at the peak of his wealth and power. Granted, the electric freight motors are gone, replaced by GP38-2s, and the old Standard Steel and Pullman interurban cars have been replaced by "modern" Nippon-Sharyo cars (themselves headed for 40 years of age now), but there's still catenary and its still in use, and the equipment is still painted the same orange and maroon it always has been.

Samuel Insull, who owned several Illinois/Indiana/Wisconsin area electric interurban lines, is an interesting case. For a guy who was very prominent throughout the pre-Great Depression era, his name has pretty much fallen completely out of public knowledge.

Born in England in 1859, he moved to the US in 1881 and immediately took a job with Edison. He was tasked with setting up electrical power stations throughout the US, and stayed on through the founding of General Edison Electric. He left though, after J.P Morgan merged the Thomas-Houston Electric Company and General Edison Electric to form General Electric. Part of it was because he was mad that he wasn't offered the position of president, but the other part was because other longtime Edison loyalists viewed Insull as a sellout for supporting the merger. Insull saw the merger, and the influx of capital from Morgan, the Vanderbilts and others as necessary for the company's future development. Thomas Edison forgave Insull, understanding his logic, but the others didn't and Insull felt it was best if he moved on.

Insull left General Electric and moved to Chicago in 1892, where he became president of Chicago Edison, formerly Western Edison Light Co. that year. Chicago Edison was losing money badly, and Insull set about trying to figure out a way to make it profitable. The solution was discovered during a visit to Brighton, England around Christmas 1894. To his surprise, he saw that the shops were closed, but every light in them was burning, something that never happened in the US. Finding the head of the town's electric company, he asked why the stores would leave the lights on. It was explained that Brighton's electricl was not a flat rate bill, but use of a demand metered billing system, with a set of rates for low-demand and high-demand electric use times. Returning to the US, by 1897, Insull had worked out his formulas enough to offer Chicago electric customers two-tiered electric rates. With the new system, many homeowners found their bills lowered by 32% within a year.

In 1897, he took over another electric utility, the Commonwealth Electric Light & Power Co., which he would eventually merge to form Commonwealth Edison. Insull also began buying up chunks of the Chicago utility infrastructure, and when it became clear that Westinghouse alternating-current was the way to go, he also made the jump to AC as well. He bought up Federal Signal Company, Peoples Gas, and Northern Indiana Public Service Company, as well as shares of other public utility companies. When he heard of Westinghouse's desire to establish a radio station in Chicago, he contacted the company and together Westinghouse and Commonwealth Edison arranged for a radio station to be built in Chicago which would be operated jointly by Commonwealth Edison and Westinghouse. KYW's first home was the roof of the Edison Company building and it went on the air November 11, 1921 as Chicago's first radio station. Though the partnership came to an end in 1926, with Westinghouse buying out Edison's interest in KYW, Insull's interest in broadcasting did not stop there. He formed the Great Lakes Broadcasting Company in 1927 and purchased Chicago radio stations WENR and WBCN. Insull's Great Lakes Broadcasting Company also included a mechanical television station, W9XR, which began in 1929 after the company installed the first 50,000 watt radio transmitter in Chicago for its two radio stations.

And since he was in the electric-supply business, he grabbed up the Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee, the Chicago, South Shore & South Bend, the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin, the Chicago Rapid Transit Compan, and the Gary Railroad, all electric trolley and interurban railroads. Under Insull, all of the railroads saw large improvements to infrastructure, equipment and service, particularly the North Shore Line. The North Shore even instituted a number of named, limited-stop trains, some carrying deluxe dining and parlor/observation cars. One of the railroad's most distinctive named trains, inaugurated in 1917, was the Gold Coast Limited. Plus, by having all these railroads under the same umbrella, they were able to work out connecting services to allow for easier travel.

Aaaand then the Great Depression came along. Insull had highly leveraged his various holdings and controlled a $500 million empire with only $27 million in actual equity. Almost overnight his holding company collapsed and evaporated the life savings of 600,000 shareholders in the process. Fearing a political lynching (in fact, FDR's campaign was based heavily on bringing Insull to justice) and possible assassination, Insull and his wife fled the country in response, first to France. When the US tried to extradite them from France, they then passed through Italy, where FDR even requested that Benito Mussolini have Insull detained and shipped home. They eventually fled to Greece, which had no extradition agreement with the US at the time. In their rush to get Insull, the Senate quickly ratified an extradition treaty with Greece, but the treaty required that a Greek court find Insull guilty first. Despite the US government sending top lawyers to Greece to argue the case in repeated trials, the Greeks never found sufficient evidence to extradite Insull. Insull ingratiated himself with the Greeks, designing a power grid for their national utilities, but was eventually ousted when the US threatened to withhold trade with Greece. Eventually arrested in Turkey, Insull was shipped back to the US, to face trial on counts of mail fraud and antitrust. After a long trial, Insull, and his son, were found not guilty on all charges.

Insull eventually moved back to France, and dropped dead of a heart attack in 1938, ironically while boarding the Paris Metro. He had the equivalent of 84 cents in his pocket. He was living on a $21,000 pension from his three companies. His estate was found to be valued at $1000, and his debts totaled $14,000,000, of which almost $5,000,000 was unpaid charity obligations.

In retrospect, Insull remains an odd one. Despite being one of the wealthiest, most powerful Americans of the pre-Depression era, appearing on the cover Time Magazine several times, and having a manhunt launched across Europe to find him, it's rare to find any real mention of him these days. Not like the Rockefellers or Carnegies or Vanderbilts, who are still well-remembered. Also, while Insull was in favor of monopolies, he simultaneously pushed heavily for regulation, creating the regulated monopoly concept. He believed that competing power producers caused inefficiency that would often double the cost of production. He also believed in the citizen's right to fair treatment. So while he bought up rival companies and created a monopoly, he kept his prices low and campaigned vigorously for regulation. Around 1912, Insull announced he had "given up" on acquiring further wealth, and during his trial was found to have spent nearly as much as he earned on any and all charities from that point on.

Also, while the character of Charles Foster Kane of Citizen Kane is always said to be based on William Randolph Hearst, it has gone almost forgotten that Kane was also partially based on Samuel Insull. Orson Welles gave Maurice Seiderman a photograph of Insull, with mustache, to use as a model for the makeup design of the old Charles Foster Kane. Also, the part where Kane's wife Susan Alexander turns out to be a "hopelessly incompetent amateur" in the opera after Kane basically buys her way into the role was based on Insull and his wife. Herman Mankiewicz, screenwriter for Citizen Kane, had in 1925 gone to see and review a performance of The School For Scandal, and Insull's wife, after a 26 year absence from the stage, had been cast as the lead character through Insull's wealth and connections. Mankiewicz, angered at the role of an 18 year old being played by a 56-year-old millionairess whose husband had bought her the role, got absolutely hammered and typed part of a review that included the phrase "hopelessly incompetent amateur" before passing out, slumped over his typewriter. Mankiewicz dusted off the memory for Citizen Kane, working it into the character of Jedediah Leland, even reusing the phrase and having him pass out slumped over his typewriter.

One of the Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee's Electroliner streamlined, high-speed, luxury interurban trainsets pauses at the Edison Court station in Waukegan, Illinois.

After the Great Depression hit, the North Shore, like most interurban and trolley lines, found itself in financial trouble and facing declining ridership. By 1940, their equipment was badly worn out, most of it dating from the '20s, and the North Shore also faced competition from the near-parallel Milwaukee Road and the C&NW. But, the North Shore did have direct downtown service to Chicago on "The Loop". The employees of the North Shore all agreed to take a pay cut to allow management to get the money together to purchase new equipment, and the St. Louis Car Company delivered the radical Electroliners. With their streamlined end cars, luxurious interiors, and high speed capabilities, the Electroliner was the shot in the arm that the Chicago, North Shore & Milwaukee needed and rapidly changed the line's reputation from that of a typical mid-western interurban to a high-speed regional commuter railroad, running at high speed between two major cities

The Electroliner's performance capabilities were never fully explored by the North Shore. Performance was typically limited to 90mph, but on a test run, full field shunt to the traction motors was briefly engaged and speeds of 110mph were seen. At that speed, the trains were literally outrunning the crossing gates: they would be in the grade crossing and the gates would just be starting to go down. For safety's sake, they were restricted to 90mph, but they did that all day long, and it's not out of the realm of possibility that motormen might have run faster if they were behind schedule.

An Electroliner and more conventional North Shore interurban cars. The Electroliner is flying white flags, so it might be running a fantrip

CNS&M #156 leads up an outbound six car train just north of Howard, going into the Skokie Valley Route. There's some sort of electric freight motor off to the far right as well. The North Shore did handle freight moves as well with an assortment of steeplecab machines, but they were painted in the North Shore's green and red, and this one appears to be yellow. The North Shore did purchase some of it's freight motors secondhand, so this could be something that hasn't seen the paint shop yet.

Norfolk Southern stringlined a freight off the Rockville Bridge yesterday. Empty center-beam flatcars near the middle of the train, and they yanked a bunch of Reading & Northern coal hoppers off the side of the bridge and dumped in the road under the bridge. I love how train composition has been an understood science for decades and now Class Is have thrown that out the window

Between these and the passenger car that NS smashed up at Decatur earlier this year, I was inspired to make this:

Yesterday I drove down to Albany to the model train show they were holding at Empire State Plaza. My main goal was perusing the books for sale, because a lot of the really good railroad books are single-printing, limited-run books from the '50s and '60s that most libraries have long disposed of.

I didn't take a ton of photos, just because it's hard to get my phone to take good ones of small things, but this Lego layout was pretty fascinating. I admittedly haven't paid much attention to the Lego stuff, but I remember when it came out, it was pretty generic. It's come a long way since then. They had built several fairly faithful replicas of 5 Central Vermont steam locomotives (an 0-8-0, three 4-6-0s, and a 2-8-0). These two Shays were also really cool.

There was also a an L-scale version of B&M #4266 and #4268, the two F7s that I rode behind up to Conway Scenic Railroad in October. They even recreated the Hattie Evans, the dining car I rode in on that trip.

There was also a an L-scale version of Adirondack Railroad RS-18u #1835 and #1845

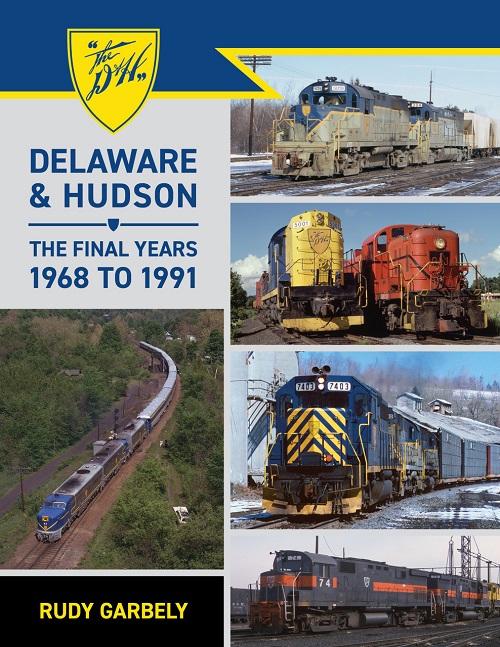

I did end up buying a book, although just to contradict myself, it was not a rare 1950s books, but a rare, limited-printing 2022 book: Rudy Garbely's Delaware & Hudson: The Final Years 1968-1991. Garbely actually set out to write a book on Conrail's formation, and discovered that it was hard to write about Conrail without touching on the D&H's role as Conrail's "competitor", and then while trying to do research realized that the last in-depth book on the D&H had been written in 1967! So he pivoted and decided to cover the D&H from when that book left off to it's purchase by CPR. It's not just a railfan's book of "Ooh, pretty pictures", it's a pretty dense tome with lots of interviews with former employees (including President Bruce Sterzing, done just before his death in October of '21) and lots of Congressional hearing transcripts and court documents. I'm not done yet, and I've learned a ton on the D&H that I never knew or have seen mentioned elsewhere. Examples include, Chessie System was originally supposed to get the E-L and Reading and be the Conrail competitor, the Boston & Maine was supposed to be part of N&W's Dereco holding company that managed the E-L and D&H but held out for a higher stock buyout price and missed the boat, PA-1 #17 broke a connecting rod in the 244 V16 circa 1972 and had a 244 V12 swapped in by the shop to run excursions, and the Baldwin sharks weren't purchased due to their rarity or because they'd be a railfan spectacle but simply because they needed more power and the two were available for scrap price. The whole book really covers how the D&H became a man that couldn't swim but just wasn't wouldn't drown, and was repeatedly undermined, thrown a lfeline, and then sabotaged again.

I picked up this gorgeous 36"x24" New York Central Systems painting as well. I was on my way out and saw this, offered for $50, and it stopped me in my tracks. The lady working the booth said her and her husband had no place to store it and it was a hassle to keep bringing to shows, and she saw me making heart eyes at it, so she said she would give it to me for $40. I couldn't get my wallet out fast enough. As she was handing it to me, another gentleman came over and went "What'd you give for that?" I told him and got "Jesus, I wish I'd come over here first" in reply.

Just peeking in on the left, you have an S-1a Niagara, then an EMD E7, then one of the 20th Century Limited Hudsons, and then an Empire State Express Hudson.

While in Albany, I caught wind that something weird was happening with Amtrak's eastbound Lake Shore Limited and that it was running 2 hours behind, did the math and realized it would be going east through Utica around the same time I was headed west through Utica to go home. So I made my day way to Utica Union Station and waited. Very telling was the fact that there were other people there with cameras and tripods and drones, something I can't ever recall seeing at Utica.

Sure enough, the Lake Shore Limited had a Norfolk Southern SD70ACu tacked on ahead of the two GE P42DCs. Apparently one of the P42s packed it in near Waterloo, Indiana in a way where it not only couldn't provide motive power, but also couldn't even be used to lead. There was no other Amtrak power readily available, so NS cut the the big SD70 rebuild off the front of an eastbound train and lent it to Amtrak to get the train over the road. Apparently not without precedent, because one of the other guys taking photos said the Lake Shore Limited had been assisted by an NS unit back in 2014.

Also snapped possibly the last photos I'll ever get of Adirondack FP10 #1502, F7A #1508 and FL9#2007. All three have been sold to Larry's Truck and Electric and will be leaving the property at some point. Judging by their condition, it wouldn't surprise me if they were parted out and scrapped. The caboose with CSX reporting marks is new though. I wonder what that's about.

Also got a photo of new kid on the block, C424 #2400, peaking out from behind a boxcar at the east end of the yard.

Photographer Marc Glucksman was also present (in fact I was standing next to him at Utica) and got photos at several different locations.

The situation got especially weird down in Hoffmans, NY, about 25 miles out of Albany. The NS locomotive is not equipped with Amtrak's Positive Train Control System and so could not lead the train on Amtrak rails into Albany-Rennselaer Station. So Amtrak brought in a pair of P32AC-DMs, which were hooked onto the front, resulting in a P32-P32-SD70ACu-P42-P42 lashup.

NS #7258 is kind of an interesting unit, because it was originally built for Union Pacific as an SD9043MAC "convertible". EMD was working on their SD90MAC, which was a 6000hp 6-axle AC locomotive that was to be powered by the new 265H engine and Union Pacific placed an order for them. But, the 265H development was taking longer than expected, so EMD sold them the SD9043MAC, which was an SD90MAC body (note the GE-style big flared radiator) and chassis with the 4300hp 710 engine from an SD70MAC. The idea was that once the 265H engine was ready for primetime, they could then be converted by removing the 4300hp 710 and installing the 6000hp 265H. UP ended up buying straight SD90MACs and was never impressed enough with them to ever convert any of the SD9043MACs to 6000hp spec, nor did any other buyers of the "convertibles", although quite a few SD90MACs were downgraded to SD70MAC-specs. Norfolk Southern ended up buying all 100 of the UP's SD9043MACs, and then ran them through a rebuild program at Altoona that refreshed the electrical components and installed the new (hideous) EMD Ultra Cab II to bring it into FRA crash compliance, emerging as SD70ACus. Canadian Pacific is also doing the same thing to their SD9043MACs, although it's being handled by outside contractors.

You'll need to log in to post.