I actually just finished Jim Shaughnessy's book on the Rutland Railroad, which was an interesting read. Not a railroad that you hear about a lot, or see a lot of photos on, partially because it ran in relatively remote territory and partially because it went out of business fairly early.

In the 1840s, Vermont came up with the idea to provide a rail connection from the Great Lakes, across the northern portion of New York, down the western edge of Vermont and then on down to Boston. Vermont chartered several railroads, all at roughly the same time, and they were supposed to all work together to interchange traffic and accomplish this goal, but very early on, the Rutland & Burlington was squeezed out by the Vermont Central and the Vermont & Canada, leaving the Rutland & Burlington mostly to run between those two cities, and the Vermont Central and Vermont & Canada did their best to avoid interchanging traffic to the R&B, which stunted its growth.

The Rutland & Burlington, through a series of acquisitions and leases, began to build itself out through the 1850s and 1860s, and the component that really breathed life into the R&B was the Champlain Transportation Company, which operated steam ships across Lake Champlain. While the Vermont Central, which was leasing the Vermont & Canada, had to go around the north end of Champlain, the Rutland & Burlington just floated their traffic directly across the lake to a connection with the D&H. This began moving a lot of traffic to the Rutland, which had dropped the "& Burlington" part of the name in 1867, and the Vermont Central eventually agreed to lease the Rutland at a substantially inflated rate in 1871. By 1896, the Vermont Central went into receivership, largely from paying far too high a lease rate on the Rutland, and the Rutland emerged as an independent company once again.

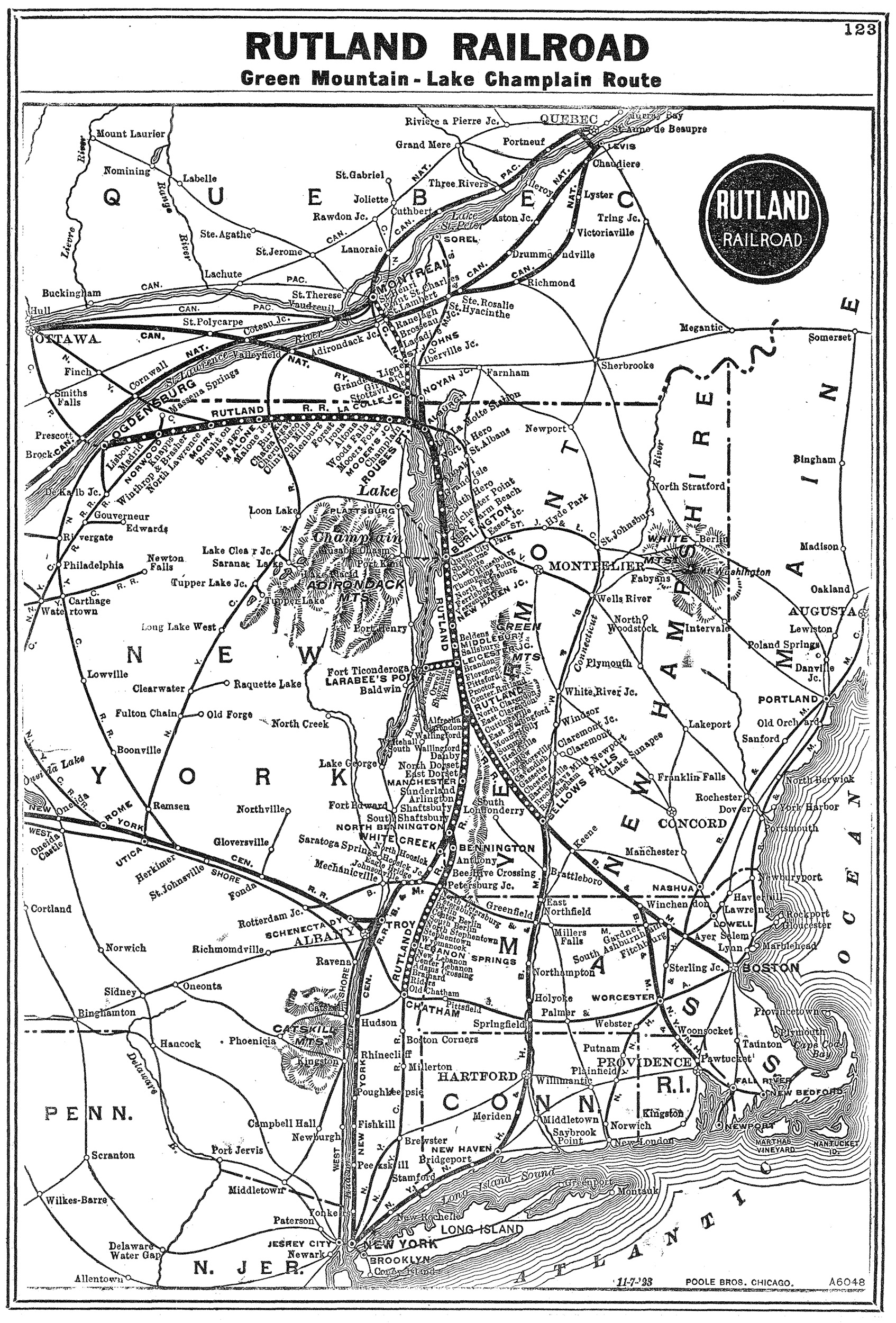

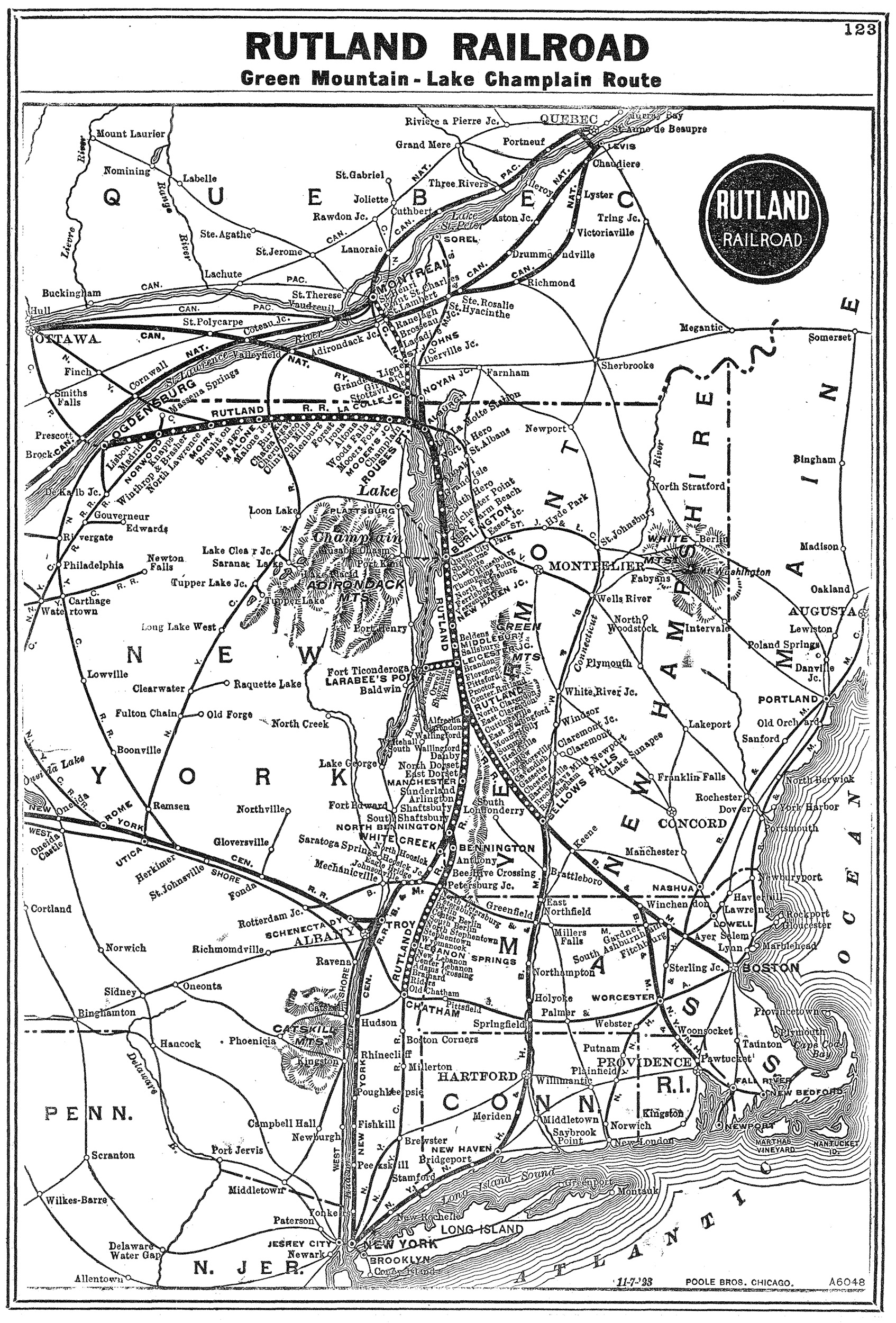

Over the next couple years, the Rutland expanded it's reach with more construction and acquisitions; to Rouses Point via a series of causeways and trestles across Lake Champlain, to Canada via the purchase of the Rutland-Canadian Railroad, to Bennington via the purchase of the Bennington & Vermont, to Chatham, NY via the purchase of cthe Chatham & Lebanon Valley Railroad, and most importantly, to Ogdensburg on Lake Ontario via the purchase of the Ogdensburg & Lake Champlain. This resulted in an inverted L-shaped railroad that ran north from Chatham along the NY-VT border, then turned left at the northern end of Lake Champlain and headed all the way across the very northern edge of NY to the Great Lakes. It also purchased a number of ships that operated across the Great Lakes to Detroit and Chicago under the Rutland Transportation Company, which made the Rutland a fairly healthy railroad. The goal of connecting directly to Boston had been given up on, but at Chatham it connected to the New York Central's Boston & Albany subsidiary, where traffic could either go east to Boston or south to New York City. The Rutland became quite dependent on milk traffic, with the first refrigerated boxcars being constructed for the Rutland for hauling milk. Unit trains of milk, often as long as 22 cars and pulled by one of the road's Pacifics, served the dairy farms of northern NY and western VT, whisking it on it's way to New York City and Boston.

In 1902, Doctor William Seward Webb assumed presidency of the Rutland. The Rutland crossed what had been his Mohawk & Malone Railroad, since becoming the New York Central's Adirondack Division at Malone, and Webb was an in-law of Cornelius Vanderbilt, who had founded the New York Central, so it all made a certain sense. Primarily, Webb, originally an inhabitant of Vermont, desired to become governor of Vermont, and saw that many railroad men went on to great careers in politics. It didn't pan out for Webb, but by 1905, the New York Central had acquired a controlling interest in the Rutland, since it fit neatly into their empire; the west end connected to the RW&O division at Ogdensburg, the Adirondack Division crossed it at Malone, it connected to the B&A Division at Chatham, and it would allow the NYC to establish a presence on the eastern border of NY, where the D&H had been operating pretty much unchecked.

The era under the New York Central's control was the first real period of health and stability in the Rutland's existence but was sadly short-lived. The New Haven became concerned over the NYC's control of the Rutland and Boston & Albany, seeing those as the prelude to the NYC's invasion of New England. In response, the New Haven acquired a controlling interest in the New York, Ontario & Western, which, while poorly-routed and financially frail, mirrored a lot of the New York Central from Weehawken to Oswego, as well as reaching the anthracite fields in Scranton and connecting with the New Haven at Maybrook Yard. This was purely a negotiating tactic; the New Haven proposed trading their controlling interest in the NYO&W for the NYC's shares of the Rutland in 1911. Talks began and the New York Central and New Haven instead settled on giving half their shares of each railroad to the other, leaving neither in control. The NYO&W was fully onboard, since it had been badly neglected and abused under New Haven control, while the Rutland strongly fought the idea, since they realized that once they stopped being a piece in the NYC empire, they would go back to struggling to make ends meet.

The Rutland fought the decision and kept it tied up in courts until 1915. Unfortunately, this backfired against them, because in 1914 the Panama Canal Act was passed and included a provision for the ICC that banned railroads from operating other forms of transportation competing against themselves unless they were operating at a loss as a necessity or convenience of the public. New York Central technically still owned the Rutland Railroad and the Rutland Railroad owned the profitable Rutland Transportation Company, so the NYC was essentially competing against itself (it moved traffic from the same points fully by rail) and the ICC forced the Rutland Railroad to close down the Rutland Transportation Company. The NYC, knowing it was going to be ridding itself of the Rutland Railroad didn't exactly fight hard against the ICC ruling.

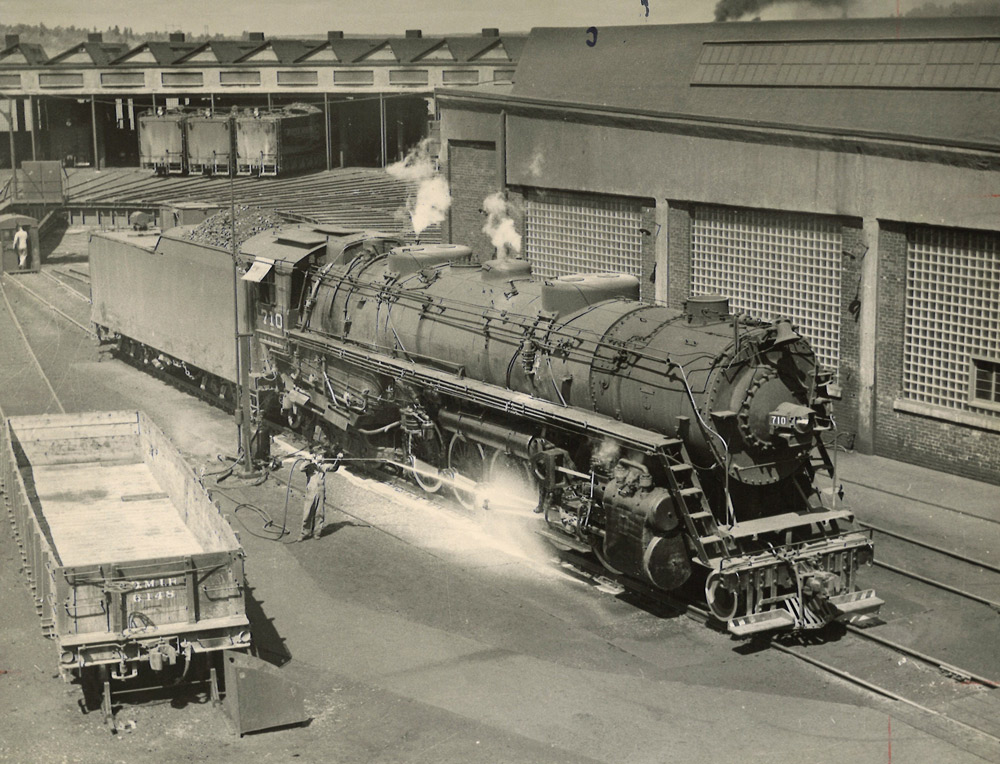

The hits kept coming. In 1917, the federal government nationalized all the railroads under the United States Railroad Administration, expecting WWI to be a more drawn-out affair and concerned about the railroads abilities to handle wartime traffic. Unfortunately, the railroads were forced to operate at a loss and saw heavy traffic, which chewed up a lot of infrastructure and equipment while depleting bank accounts, and by the time they were returned to private control in 1920, most of them were in a state of serious disrepair. The Rutland was one of the many railroads that was wrecked by USRA control, although they did at least get six USRA Light Mikados and two USRA 0-8-0s out of the deal. Granted, the 0-8-0s, allotted to the Rutland during the war, were diverted to the NYC instead and didn't arrive on the Rutland until after USRA control ended. This was followed by a severe flood that wiped out most of the Vermont railroads in 1927, followed by the Great Depression, and finally it was pushed into receivership in 1938.

The Rutland's creditors actually filed for liquidation, but there was a strong push by customers, towns and villages that it served, and even the Vermont government to keep the railroad alive. Many of the towns and customers served by the Rutland were quite remote, and the state realized that if the railroad went out of business, they might be forced to construct highways, to the tune of $10-12 million in 1938 dollars. The "Save The Rutland" campaign worked, and money was raised to get the railroad back on it's feet, while the state lowered it's tax evaluation and also provided bailout money. The Rutland even introduced a new named fast freight "The Whippet", which was pulled by an old Consolidation that was semi-streamlined just for the service. Still, the Rutland barely dodged a bullet when the unions, believing the Rutland was now flush with cash, made a movement to strike unless they got a raise. The Rutland, which was really spending all the money on new cars and rebuilding their roadbed, managed to avoid a strike by giving a small raise, but it was a prelude of struggles to come.

WWII brought renewed traffic to the Rutland, and the railroad purchased it's last steam power, a trio of gorgeous light Mountains, in '46. But post-war saw the same story as everywhere else; passenger traffic dropped off and highway developments stole away traffic. The Rutland was especially hard off, because it really had very little on-line traffic. Western Vermont was lacking pretty much any heavy industry or large population centers. It was mostly just agricultural traffic and some bridge-line traffic. In 1950, the Rutland reorganized and emerged from receivership, again with much assistance from the state, through the reduction of tax valuations, deferral of tax payments and some state investment .

.

The reorganization saw the Rutland Railroad become the Rutland Railway and the new management immediately launched into a trimming down of the railroad. Total employment was cut back, diesels were ordered, as much unprofitable traffic was ditched, and passenger service was abandoned where it could be. In 1951, the Chatham branch, also nicknamed the "Corkscrew Division" for it's torturous routing, was approved for abandonment, since it developed zero on-line traffic, and Rutland moved it's traffic to Chatham via roundabout trackage rights agreements with the NYC and Boston & Maine.

The biggest move was the purchase of sixteen diesels; 10 Alco RS-3s and 6 Alco RS-1s, spread across several orders. They replaced the old teakettle Ten-Wheelers and Consolidations first, then the newer Pacifics and USRA Mikados, and finally the L-1 Mountains. Shaughnessy's book tells how the new president of the railroad, installed in the 1950 reorganization, came across a grade crossing while heading home one summer evening, and stopped as an L-1 Mountain came storming up a grade, putting on a show as it raced into the twilight, the crew waving and whistling as they passed, and he claims to have shed tears because he had ordered several RS-3s just the week before and signed the death warrant of the L-1s. Not a single Rutland steam engine escaped the torch, as the scrap money was needed to fund the purchase of the diesels.

Unfortunately, labor troubles reared their heads again and on June 26, 1953, the Rutland was hit by strike, the first strike in Rutland history. The unions has been working below the national average since before the railroad went into receivership in 1938, and assumed that, due to the reorganization and investment into the railroad, the railroad's bank accounts were flush with cash. this was not the case, and after three weeks of striking, a compromise was reached. All crews would receive a minor raise, along with retroactive pay, although they woul;d still be under national average. The strike did have a positive effect on the Rutland, oddly. Passenger service, which was always sparesely-ridden, had been halted and in those three weeks, the passengers all went to other methods of transportation. When the Rutland resumed passenger service, they found they had absolutely zero riders any more and, with ICC permission, all passenger service, long a drain on the line, was completely eliminated

The '50s brought further decline in service, although the Rutland tried to reinvent itself as a bridge line, since there was little on-line traffic left anymore, other than a marble quarry at Florence, Vermont, and the Howe Scale Company in Rutland, VT. Construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway brought a rush of traffic to the Rutland, moving construction materials, but then all that traffic was lost as soon as the Seaway opened and the Seaway also stole away a lot of their bridge traffic. Still, the Rutland was in good physical shape and had zero outstanding debt, with the diesels having been paid off rapidly. It even managed to pay dividends in 1956, 1957 and 1958.

As part of a further effort to streamline operations, employees were trimmed down from 1200 to 400, and in the summer of 1960, it began discussing changes to operating rules and division points, mostly eliminating a division point and moving the center of operations from Rutland to Burlington, requiring many of the employees to relocate. The changes would also have lengthened the total time of runs from Burlington to both Bellows Falls, VT and Ogdensburg, NY, due to their creation of a new overnight stop that would delay returning trains until the following day. Under operating orders in place at the time, crews would make the run from Rutland to Burlington or Bellows Falls and back in a day, or from Malone, NY to Ogdensburg and Burlington and back in a day. The Rutland shut down for 41 days on September 16th, 1960, as the employees struck and the Rutland was forced to stick to the old operating plan with three separate divisions. Then on September 25, 1961, the unions struck again, this time demanding a pay raise to bring them in line with national averages. The Rutland fought back, saying that while the railroad was operating at a small profit currently, giving the employees those raises and being forced to maintain the three divisions would force the railroad to operate at a significant loss, and so the Rutland filed for complete abandonment.

The Rutland sat quiet for two years as the negotiations dragged on. The unions refused to budge on either point, and the Rutland refused to operate at a significant loss. And the longer the strike dragged on, the more it's remaining customers moved away to other methods of transportation. Finally, on September 18, 1962 the ICC approved the abandonment application, effective January 29, 1963. The state of Vermont feared the loss of the rail network, and the Rutland was in good physical condition, so the state tried finding buyers for the line, getting a postponement of the abandonment to effective date May 20th, 1963. When no buyers showed up, Vermont came up with the radical (for the time) plan to buy up the lines that had potential for $2.7 million and then find operators for the line. Not uncommon now, but this was literally the first time anything like this had been done.

The line west, from Alburgh, across Lake Champlain, through Rouses Point and Malone and over to Norwood, NY was all abandoned an torn up in 1964. The NYC had abandoned the north end of the Adirondack Division in 1961, and then Malone lost it's other railroad in '64, going from two railroads to none in just three years time. New York took ownership of the Ogdensburg to Norwood end of the line. The Middletown & New Jersey's president formed Vermont Rail System to take over the old Rutland mainline from Burlington down to Rutland and then the branch down to Bennington. Nelson Blount, searching for a place to house his steam locomotive collection and host excursions, was persuaded to take over the line from Bellows Falls north to Rutland, and handle freight services as well under the Green Mountain Railway Company.

The very last official move of the Rutland came in early 1964. Nelson Blount's collection was in North Walpole, NH and needed to be moved to Bellows Falls, VT and the B&M was dragging their heels on allowing his equipment to be moved. It got down to the day before Steamtown was supposed to open and the equipment was still stranded across the river. The Rutland still existed, although much of the equipment was sold off, and would exist until the midnight that night, at which point it would become Green Mountain. The remaining Rutland employees came up with the idea to call the B&M and request a special move. They then asked Blount for a list of the equipment he absolutely needed to run, and under cover of darkness ran Rutland RS-1 #405 over to North Walpole, grabbed a locomotive a couple cars, and shuttled them back to Bellows Falls before the B&M could catch on. And with that, 120 years of the Rutland came to an end.

.

.