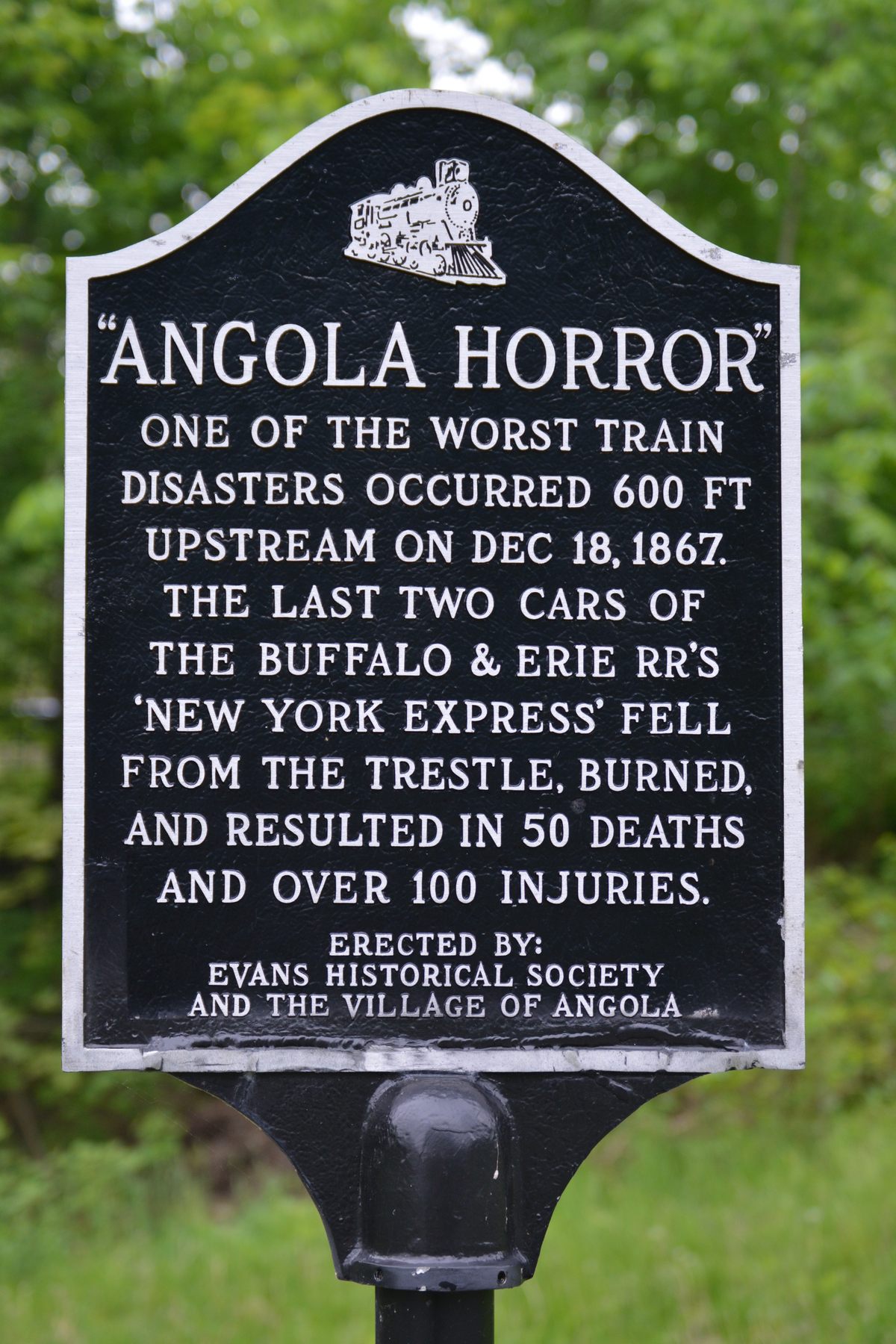

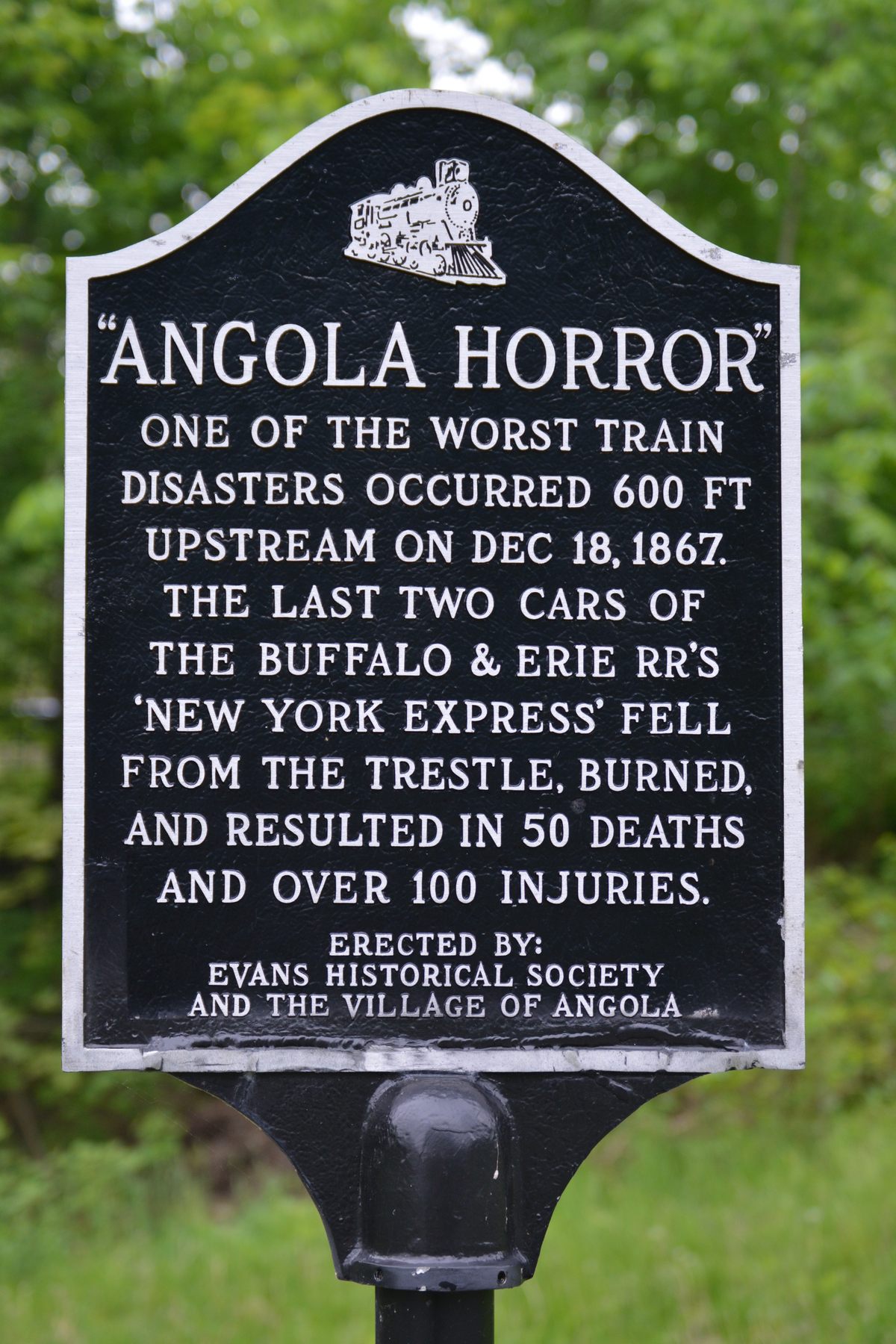

Also, I got off the thruway at Angola, NY to get to Gowanda, and Angola is a town that lives in infamy in railroad history as the site of "The Angola Horror", a horrific train accident that killed 49 people on December 18th, 1867 and ushered in legislation that standardized the gauge width in the US.

In the early years of gauge width was not commonly agreed on. What became standard gauge, 4' 8.5", was common, but anthracite railroads were fond of 6' gauge, the state of Ohio had it's own gauge (4'10"), the South preferred 5' gauge (the ET&WNC was built to 5' broad gauge, then converted to 3' narrow gauge before it ever ran a train!) and there were a bunch of other weird gauges kicking around. Partly, it was viewed as a sign of financial strength if your railroad could not interchange with other railroads, since it meant your railroad was strong enough to go it alone. Some of it was also done by cities to force service disruptions to other cities. Pennsylvania, for example, banned Ohio gauge, forcing the Erie & Northeastern to regauge their line through Erie, PA into standard gauge. That meant that eastbound traffic would have to stop at Erie, change onto standard gauge cars, then change back to Ohio gauge at the NY border. The hope was that to avoid having to be transloaded twice, freight traffic would start using Erie as a Great Lakes port rather then Buffalo.

A number of remedies to avoid travel interruptions were attempted. Chief among them and relevant to this tale were "Compromise cars", which were built with 5" wide wheels, an inch wider than normal, to allow them to travel on standard tracks and on Ohio gauge tracks. The New York Express of the Lake Shore Railway (later a component of the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern, which later still became a component of the New York Central) was traveling on the Buffalo & Erie (a merger of the Erie & North East and Buffalo & State Line and owned by Lake Shore Railways) on the final leg into Buffalo. The consist was four "compromise car" wooden passenger cars, with two pot-bellied stoves for heat in each car and kerosene lamps for lighting. The train had lost time on the journey, and by the time it passed Angola, it was running 2 hours and 45 minutes late, and was trying to make up lost time.

As the train neared the bridge over Big Sister Creek just east of Angola at 3:11, it ran over a crossover and the front axle of the rear car, which was slightly bent, jumped off the track as it hit the frog, derailing the rear car, which then swayed violently from side to side. The brakes were applied, but the train still traveled at considerable speed as it crossed the bridge. The last car uncoupled from the train and plunged down into the icy gorge. The second-to-last car also derailed, but made it to the other side of the gorge before sliding 30 feet down the embankment

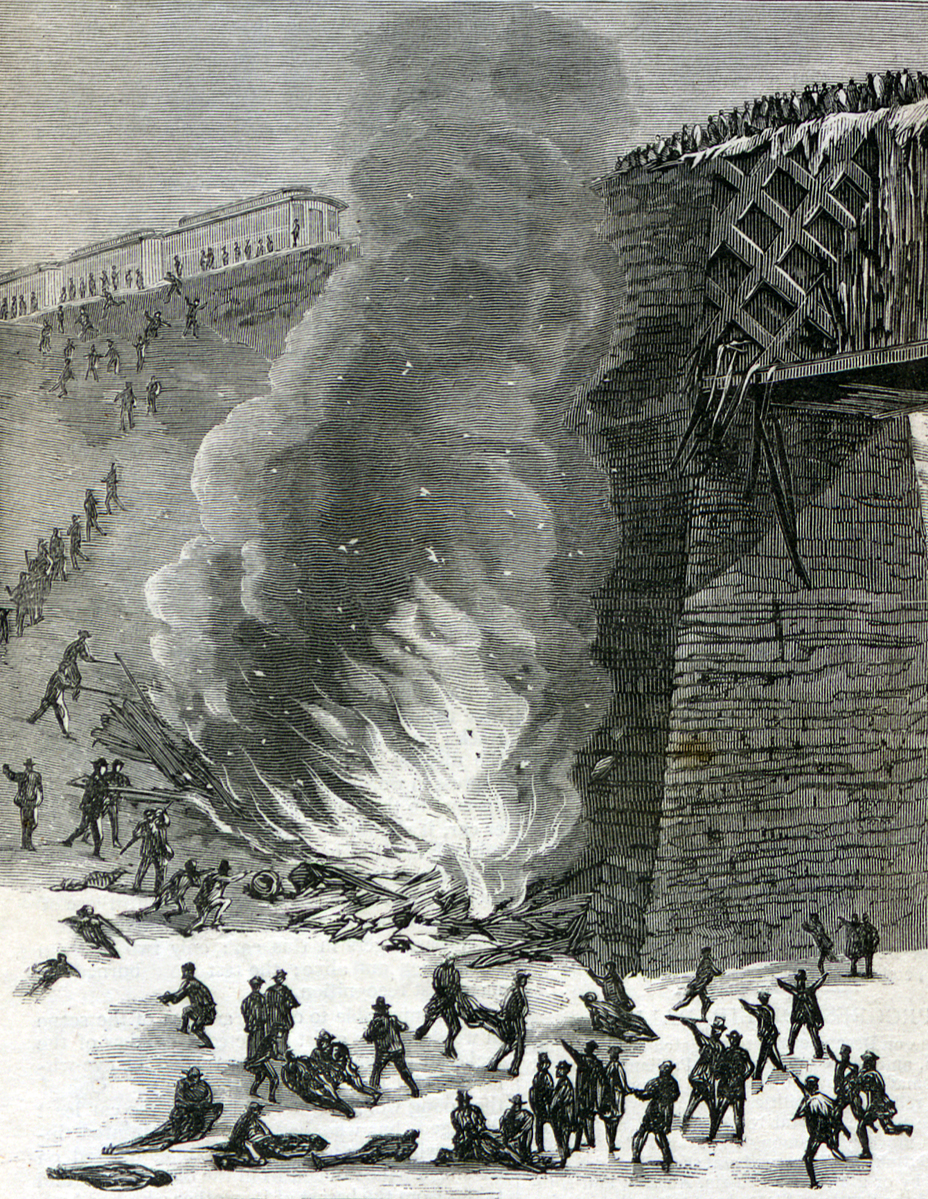

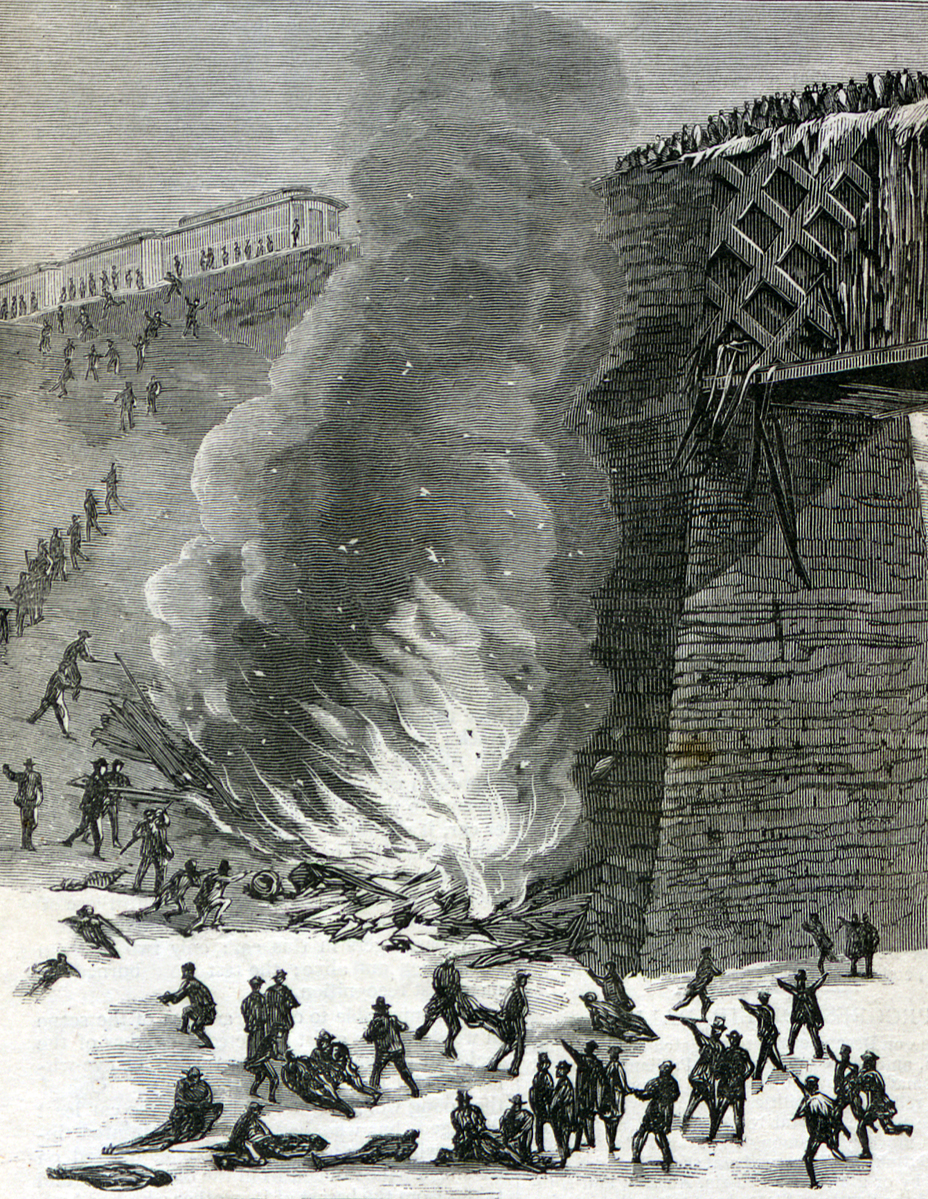

Having slid down a 40 foot embankment, the last carriage immediately caught fire. The passengers fell to one end of the car, on top of one stove, with the other stove spilling the burning coal out of it. The fuel from the kerosene lamps and the wooden coach construction fueled the flames. Only two people escaped alive from the carriage, and while some may have been killed from the fall or suffocation, the majority were burned alive. Witnesses spoke of hearing the screams of those trapped inside lasting for five minutes. The accident, dubbed the "Angola Horror", gripped the imagination of the nation. Accounts of the tragedy, accompanied by grisly illustrations, filled the pages of newspapers for weeks and showed the tragedy of those trying to identify their loved ones among the charred remains that were pulled from the wreckage.

In the wake of the accident and the public outcry, many railroad reforms soon followed, including the replacement of loosely secured stoves with safer forms of heating, more effective braking systems and the standardization of track gauges.

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Chicago, Illinois. A worker in the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad locomotive repair shops]](https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/fsa/8d23000/8d23800/8d23835r.jpg)