In reply to Gearheadotaku (Forum Supporter) :

RE is the reporting mark for Relco, which is a locomotive lease and overhaul company. That's an Alco S1, old 660hp yard switcher built between 1940 and 1950. I'm curious why it is partially derailed.

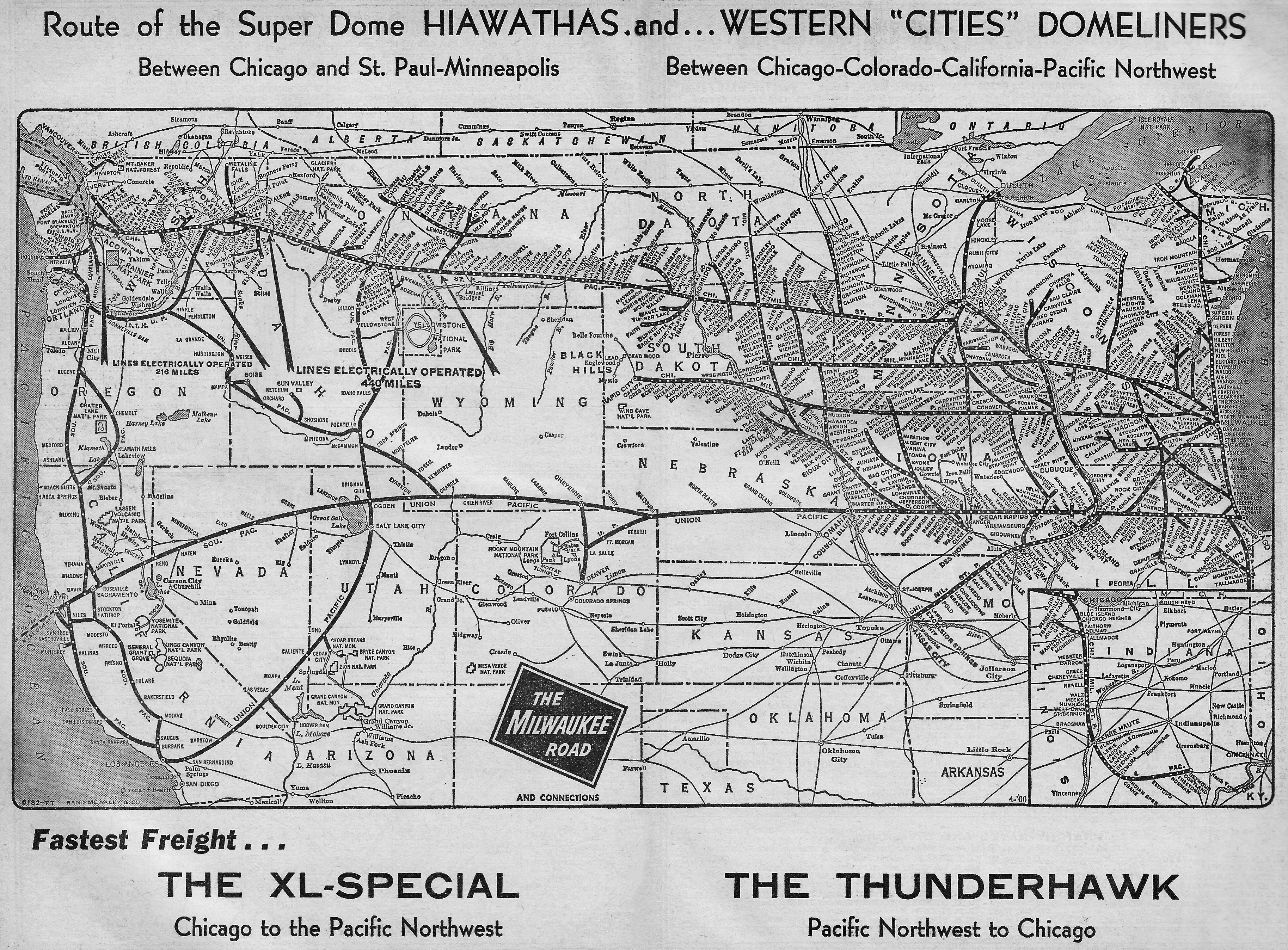

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific's Pacific Coast Extension was always a controversial route, viewed as both superior to its competitors and a complete failure, a mistake that should never have been constructed and simultaneously a tragedy that it was abandoned.

In the 1890s, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul decided that, like their major northwester competitors, Northern Pacific and Great Northern, they too needed to reach to the Pacific coast and become a transcontinental railroad to stay competitive against the Gould and Harriman and Hill railroad empires. While GN and NP frequently interchanged onto the CM&StP (or the CB&Q) to get access to Chicago, it generated relatively little revenue for the CM&StP. Long-haul freight was much more profitable, and they wanted their own route to the west coast to cash in on that. So in 1901 they had a route to Seattle mapped out, with a $45 million dollar estimate. When construction began in 1906, the estimate had now climbed to $60 million, about $1.7 billion today.

The problem was, while the government had been very heavy on promoting transcontinental railroads during the post-Civil War era and had given GN, NP, Union Pacific and Central Pacific huge land grants, by the time the CM&StP began construction, that program had basically ended, with the US figuring there was enough transcontinentals that they didn't need to promote their construction anymore. So the CM&StP was forced to buy all the land that they needed, often at high prices, as well as buying out existing smaller railroads along their route to incorporate them. Also, GN and NP had already picked the more choice routes out, so CM&StP had to build where they could, resulting in a line that crossed 5 mountain ranges and had sharp curves and some steep grades as well as a number of long trestles and tunnels, including the 8000ft long St. Paul Pass Tunnel. This route also missed most major population centers on the way to Seattle, resulting in very little local traffic, despite nearly paralleling the NP's route.

The upside was, while the route crossed more mountains, it was more gently graded over many sections, which meant higher speeds. While it missed most population centers, that meant that the line wasn't clogged up with local traffic. It was also a shorter and more direct route back to Chicago, further resulting in shorter transit times. And while GN and NP still had to interchange onto other railroads (the CB&Q or the CM&StP) for the final stretch into Chicago, the CM&StP was the only transcontinental who extended from Seattle to Chicago over their own rails.

After 3 years of construction, the 1400+ mile PCE was complete and just 2 months after completion it was opened to freight traffic, with passenger traffic beginning a year later in July of 1910. The CM&StP rolled out two new heavyweight long-distance passenger trains, the Olympian and the Columbian, to celebrate the fact and to compete with NP and GN long-haul trains. But they quickly learned that the PCE was a difficult environment to operate steam locomotives in, between the sharp curves, cold temperatures and high altitudes. So in 1914, with access to numerous hydroelectric plants in the mountains and copper mines in Anaconda, Montana, they decided to electrify 645 miles of the PCE from Seattle to Othello and Avery to Harlowton, making it the longest electric freight operation in the world. There was a 200 mile gap in electricity between Avery and Othello that was never completed due to them running short on money. Between construction of the rail line and the electrification project and new locomotives and purchasing numerous smaller railroads off the extension to operate as branch lines, the total cost of the PCE cost a staggering $257 million. To fund it, the CM&StP sold bonds which began to come due in the '20s. Combined with traffic that never materialized as planned, and purchase of multiple small railroads that were heavily indebted to Indiana, the CM&StP went bankrupt in 1925.

Reorganizing in 1928, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul became the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific but now began to go by the official nickname of Milwaukee Road instead. The Great Depression hit in '29 and even with surge traffic during WWII and an estimated $1 million a year savings from electric operations, the PCE, while reliable and efficient in operation, was still not turning a profit. The Milwaukee Road went bankrupt again in '35 and would operate under receivership until 1945.

Post WWII were the best years of the PCE, with the Olympian Hiawathan replacing the Olympian until 1961, at which point they discontinued it due to lack of ridership. They launched long-haul Trailer-On-Flatcar trains that turned huge profits and took advantage of the faster uninterrupted travel times, even naming two of the long-haul fast freight trains, the XL Special and the Thunderhawk. And when the Hill Lines of GN, NP, Spokane Portland & Seattle and CB&Q merged to create Burlington Northern, the Milwaukee Road gained new interchange points and trackage rights. During this time period, The Milwaukee Road was moving 80% of the traffic originating in Seattle and nearly 50% of container traffic moving in the PNW.

But the end of the PCE, and Milwaukee Road in general, was already underway. Since President William John Quinn had taken over the Milwaukee in 1957, Quinn had been obsessed with merging the Milwaukee Road with another railroad and had essentially given up on running a railroad to focus on marrying the Milwaukee off. Banking on a merger with competitor Chicago & North Western for 5 years, the merger was declined in 1969 when the Interstate Commerce Commision imposed terms that the C&NW would not agree to. In 1970, C&NW would offer to sell out to Milwaukee, but by that time, Quinn had realized they needed to merge with a larger line, not a smaller one. Milwaukee would turn around and immediately try to get in on a proposed Union Pacific-Rock Island merger but the ICC declined the Milwaukee Road's proposal to be included, and then the Union Pacific realized the condition of the Rock Island and backed out of the merger anyways. In '76, the Milwaukee Road would also try to petition to be merged into Burlington Northern, citing it's poor financial condition, but would again be turned down by the ICC.

All the time that they were chasing a merger, money was not being put into facilities in an effort to try and make their finances look better. Locomotives were being run into the ground, suffering failures on the road due to neglect and deferred maintenance, forcing Milwaukee to beg, steal and borrow motive power from leasing companies and other railroads. In an attempt to free up cash, they sold off their fleet of wholly owned cars and then leased them back for low rates. But the rates went up over time and more cars needed to be sold to pay off the lease payments, plus the cars they were leasing back were already run down and obsolete. Due to the high lease payments, they could not afford to purchase newer cars, and so as cars failed, they often found themselves short on cars to use.

The PCE fell into disrepair as maintenance had essentially halted in the late 1960s. In the early 1970s, Burlington Northern was paying for trackage rights to run their express freights over the PCE and was imparting noticeable wear and tear on the tracks, but the trackage rights for the extra 4 trains a day was not enough to pay for the repairs. Soon the line was clogged with 10mph orders over many sections, eliminating its advantage of a faster, shorter, more direct route, and derailments became commonplace. The electric infrastructure and the locomotives (most approaching 60 years olds) was beginning to show its age and GE made an offer to overhaul the catenary, substations, generators and locomotives for a firesale price, but Milwaukee declined. In 1972, they deemed the new GE U-series and EMD SD40-2s powerful enough to handle trains over the PCE and they stopped using electric locomotives on the Othello to Seattle stretch known as the Coast Division. In 1974, they retired their electric locomotives, ripped down the catenary and scrapped everything, right as the fuel shortages hit and diesel prices went through the roof, immediately highlighting the shortsightedness of the decision.

In 1977, the Milwaukee Road entered bankruptcy a third time, after losing $100 million dollars between '74 and '77, and in 1979 made the announcement that they were going to scrap 1100 miles of the PCE west of Terry, Montana. This made the Milwaukee, the last transcontinental railroad constructed, the only transcontinental railroad to lose that status of their own choosing.

Three years later, the Chicago, Milwaukee, Saint Paul & Pacific finally ceased to exist, swallowed up by Soo Line.

To this day, the Pacific Coast Extension is a hotly debated subject. On one hand, many say it was a mistake to build and electrify, that is route avoiding most major settlements was why it was largely never profitable, and that its construction led to the end of the Milwaukee Road. After all, it was cited as a cause of bankruptcy on all three bankruptcy filings (and yet none of the bankruptcy trustees ever wrote it off, with it carrying the debt to its inclusion into Soo), and the Milwaukee Road actually started to turn a profit after it tore up the PCE and downsized in '80.

On the other hand, there are those that say that today its faster more direct routing would be worth its weight in gold, that its failure to turn a profit was due to poor decision-making on the management's part, and that maybe if the Milwaukee Road had cut the deal with GE for the overhaul of its electrification instead of removing electric operations right as fuel prices spiked and buying new diesel locomotives, things might have played out differently.

Milwaukee Road ran 4 different types of electric locomotives over the PCE from 1915 to 1974. Most of them were Alco-GE, with one exception.

EF-1 "Boxcabs": The first of the electric locomotives that MILW took delivery of, the highly-successful EF-1 was built by Alco-GE and referred to as "King Of The Rails" in a silent promotional film. Delivered in permanently coupled sets of 2, these 42 box-cab electrics had a 2-B-B+B-B-2 configuration, generated 3340 continuous horsepower, with a one hour 4100hp surge output, and were designed as a freight motor, with a top speed of 35mph. Some were originally delivered as a passenger configuration, called an EP-1, but were then converted to EF-1s with the arrival of purpose-designed assenger motors. Later in life, a rebuild program gave them 45mph capability, as well as MU capability so that they could control diesel locomotives hooked up to them. MILW also experiemented with creating three unit sets, called an EF-2s. There was an EF-3, which was an EF-1 that was split and had a EF-1 motor with a removed pilot truck (called a bobtail) mounted between them, and then an EF-5, which was a 4-unit set. And an ES-3 was a single half of an EF-1 used as a switcher. Later on they converted a few EF-1s back to EP-1 passenger motors to help the aging EP-2s out as well. The fleet was largely intact until the '60s, at which point old age and deferred maintenance took its toll and they began to be retired as they were rendered irreparable, but one did operate until the end of electric operations, and both an EF-1 and an ES-3 are preserved.

EP-2 "Bipolar": After the success of the EF-1s, MILW decided to purchase dedicated electric passenger motors as well. They originally wanted to purchase 15 of them from ALco-GE, but the USRA was still exerting some waning influence over the railroad industry in the post WWI era and said that MILW had to split the order between GE and Westinghouse. As a result, they only received 5 EP-2s from Alco-GE, at the cost of $200,000 a piece. Radically advanced for the era, the 1-B-D+D-B-1 configured units used bipolar DC motors that were mounted directly on the axle, eliminating gear whine and motor noise. They were also unique in their articulated 3-piece construction: the center section contained steam heating boilers, while the outer ends carried the electrical gear and the operator cabs in two semi-circular bodies. Designed to handle any passenger train by themselves, they generated 3130hp and were capable of 70mph. A 1953 overhaul was supposed to give them numerous upgrades, including a more streamlined body, roller bearings, improved boilers and more motor shunts for higher speed operations. The first unit was rebuilt at the Tacoma shops and performed as hoped but went over budget and so the remaining 4 were rebuilt at the Milwaukee shops, who did not work on electric locomotives normally. While visiting the shop, Electric Department Head T. B. Kirk, stated that he saw a group of disconnected wires in a newly rebuilt EP-2 bundled together and tagged with a written message, "We don't know where these go". After the rebuild, the EP-2s began to see numerous problems with electrical failures and fires and saw decreased usage. By 1957, they were bumped from the Coast Division to the Rockies Division, but the higher speeds on the Rockies Division caused them to fail more frequently and by 1960 all 5 were retired. By 1962, all but one were scrapped, with the remaining unit donated to MOT in St. Louis.

EP-3 "Quill": As mentioned, while MILW wanted to purchase 15 passenger motors from GE, the USRA insisted the order had to be split between two companies, so instead, they received 10 box-cab units from Westinghouse-Baldwin. Using a 2-C-1+1-C-2 layout with a single non-articulated body and frame, it was essentially a pair of Pacifics bolted back to back and even used a set of 68" drive wheels like would be found on a steam locomotive. The nickname came from an odd drive system that I cannot even begin to comprehend when I read the description, but was very similar to what PRR's GG1 would use. Very similarly designed to the New Haven's Westinghouse-built EP-3 "Flat Bottoms", the problem was that while NH's Flat Bottoms ran on realtively flat straight track, MILW's Pacific Coast Extension had much different requirements. While powerful, fast and smooth-riding, they were too rigid and lightly built and suffered issues with excessive wheel wear, broken drive wheels and cracked frames. The large drivers also made them prone to derailments, and the heavy weight of the locomotive magnified the severity of the derailments. In 1922, meetings were held to try and address the issues with the Quills, and Baldwin suggested cutting the frames and bodies in half and articulating them. MILW, doubtful that would solve the issue, only rebuilt one as such and found it still had the same problems. MILW would later perform the same modification again but with a completely rebuilt frame and new trucks, but found that the cost wasn't worth the trouble. As the EF-5/EP-5s arrived in the late '40s, MILW was all too glad to retire the 7 remaining Quills (3 had been destroyed in derailments) and scrapped all of them between '52 and '57.

EF-4/EP-4 "Little Joe": Designed post-war by Soviet engineers working with GE staff for USSR railroads, 20 of them were constructed but were not delivered to Russia after relations between the USSR and USA fell apart. The Milwaukee Road purchased 12 of them, plus spare parts, for little more than scrap value at the start of the Korean War after a coal strike forced them to send their oil-burning steam engine on Lines West to take over for the coal-burning engines on Lines East. The "Little Joes", for Josef Stalin, were the most powerful single-unit electric motors at the time, making 5110hp on a 2-D-D-2 frame. Originally unimpressed by their performance, MILW performed a slew of modifications to both the locomotives and their substations and began using them in both passenger and freight trains. Powerful, fast and extremely reliable, the Little Joes closed out electric operations on the Milwaukee Road, running right up until 1974, after all the Boxcabs, Bipolars and Quills had been retired. Today 5 are preserved, ne Milwaukee unit, two Chicago, South Shore & South Bend units and 2 Companhia Paulista de Estradas de Ferro units in Brazil.

While the Milwaukee Road and the Pacific Coast Extension and the streamlined Hiawathas and the overhead catenary may all be long gone, there is still one lone reminder of the Milwaukee Road pounding the rails: #261, one of their handsome S3 4-8-4s.

You'll need to log in to post.