Virginian also played around with electric locomotives. In 1922, at the cost of $15 million and over a 3 year construction period, they electrified 134 miles of track. It was the longest stretch of continuous mountain electrification and used an 11,000v alternating current catenary system powered by Virginian's own powerplant at Narrows, VA. Virginian ran through pretty rugged territory and electric locomotives were immensely powerful, and since they had access to bituminous coal fields, they had a steady source of cheap fuel for power.

The original locomotives were Alco-Westinghouse 1-D-1 configuration boxcabs. They were referred to as either an EL-1A, and EL-2A or an EL-3A, with the number referring to the amount of units in the set, and made 2000hp each and used the jackshaft method of power transmission . What looks like a lead drive wheel does not actually contact the rails and is the end of the motor, with a connecting rod hooking it to the 2 drive wheels. An EL-3A weighed over 1.2 million pounds, generated 230,000lbs of tractive effort and was over 152 feet in length, making them powerful but also abusive on the track infrastructure.

%20Roanoke,%20VA%20(4%20Sept%201953).JPG)

In '48, to supplement the aging boxcabs, Virginian approached GE for new units, and GE responded with huge B-B-B-B+B-B-B-B semi-permanently paired streamlined cab units that used recently developed AC rectifier technology to take full advantage of AC power. A single pair of EL-2Bs made was 150ft in length, weighed 1 million pounds and generated 6,800hp and 260,000lbs of tractive effort but, with more feet on the ground and no side rods making hammer blow impacts on the track, were much easier on the roadbed. Virginian purchased 4 two-unit sets.

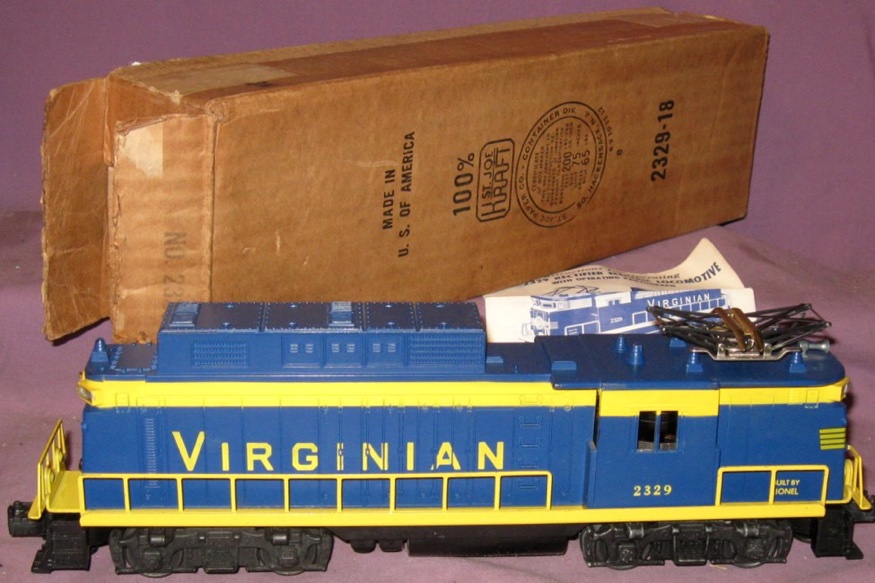

In 1955, Virginian again returned to GE for more electric locomotives. This time they purchased 12 of a road switcher style electric locomotive of a C-C wheel configuration, which they called an EL-C. These were the first electric locomotives to succesfully utilize ignitron arc rectifier technology. They generated 3300hp and made 96,000lbs of tractive effort, while weighing 158 tons. Their arrival led to retirement of all of the old Westinghouse boxcabs. The EL-C was a catalog offering by GE, but with few railroads running electric freight operations, no other customers ever appeared.

The Virginian electrified line met its end in '59 though. After years of trying to acquire the Virginian, Norfolk & Western finally received approval from the ICC to purchase the Virginian. The small but massively profitable Virginian had been a thorn in the sides of the N&W and C&O for years and both had tried repeatedly (N&W even briefly operated the Virginian during WWI under the USRA's orders) and N&W finally won out. N&W almost immediately routed all westbound traffic, with the Virginian line only handling eastbound traffic. This reduction in traffic led to the immediate retirement and scrapping of the four EL-2Bs, leaving only the 12 new EL-Cs. After 3 years, the N&W decommisioned the electrification, finding it surplus to requirements.

The EL-Cs were the only VGN electrics to escape scrapping. The New Haven, under the disastrous leadership of Patrick McGinnis, had torn down a large portion of the catenary, despite financial consultants saying not to, and put all their big electric freight motors out to pasture in favor of dual-mode EMD FL9s. After it's '63 bankruptcy, the bankruptcy trustees realized that McGinnis had really had no clue what he was doing, and so they restrung catenary and purchased 11 EL-Cs (N&W had converted one to a yard slug) and all the spare parts for a firesale price, repainted them and reclassed them as an EF-4.

Then, in '68, they passed into Penn Central ownerships and were painted in the black with the "mating worms" logo and again reclassified as an E33.

In 1976, they again changed hands, becoming property of Conrail, who ran them until they ended electric operations in the early '80s

Two of the EL-Cs, the only Virginian electrics in existence, are preserved, one in Roanoke at the Virginia Museum of Transportation in Virginian livery, and the other at Illinois Railroad Museum in bedraggled Conrail Blue.

%20Roanoke,%20VA%20(4%20Sept%201953).JPG)

4

4

.jpg)