The Ukrainian offensive brings up a number of tactical, operational, and strategic issues that it may be useful to address.

Tactically, the Ukrainians have be adopting Western methods designed to fight against forces using Russian doctrine (which looks a lot like Soviet doctrine in many ways). This can be seen in the focus on interdiction and attriting supplies and LOS over the past few weeks. The use of battlefield-level PGMs - HIMARS and guided artillery rounds - has made this possible. Russian manpower and frontline numbers were always a factor that the West could not counter in kind, so they had to come up with other solutions, usually technological ones; the Ukrainians are benefiting from being in a tactically similar situation to the one NATO faced for decades. This has validated many Western decisions in armaments and doctrine, but those lessons are not only going to be absorbed in the West. It remains to be seen, however, whether the Ukrainians can effect the sort of rapid, coordinated counterattack operation that represents the next phase in the Western offensive concept.

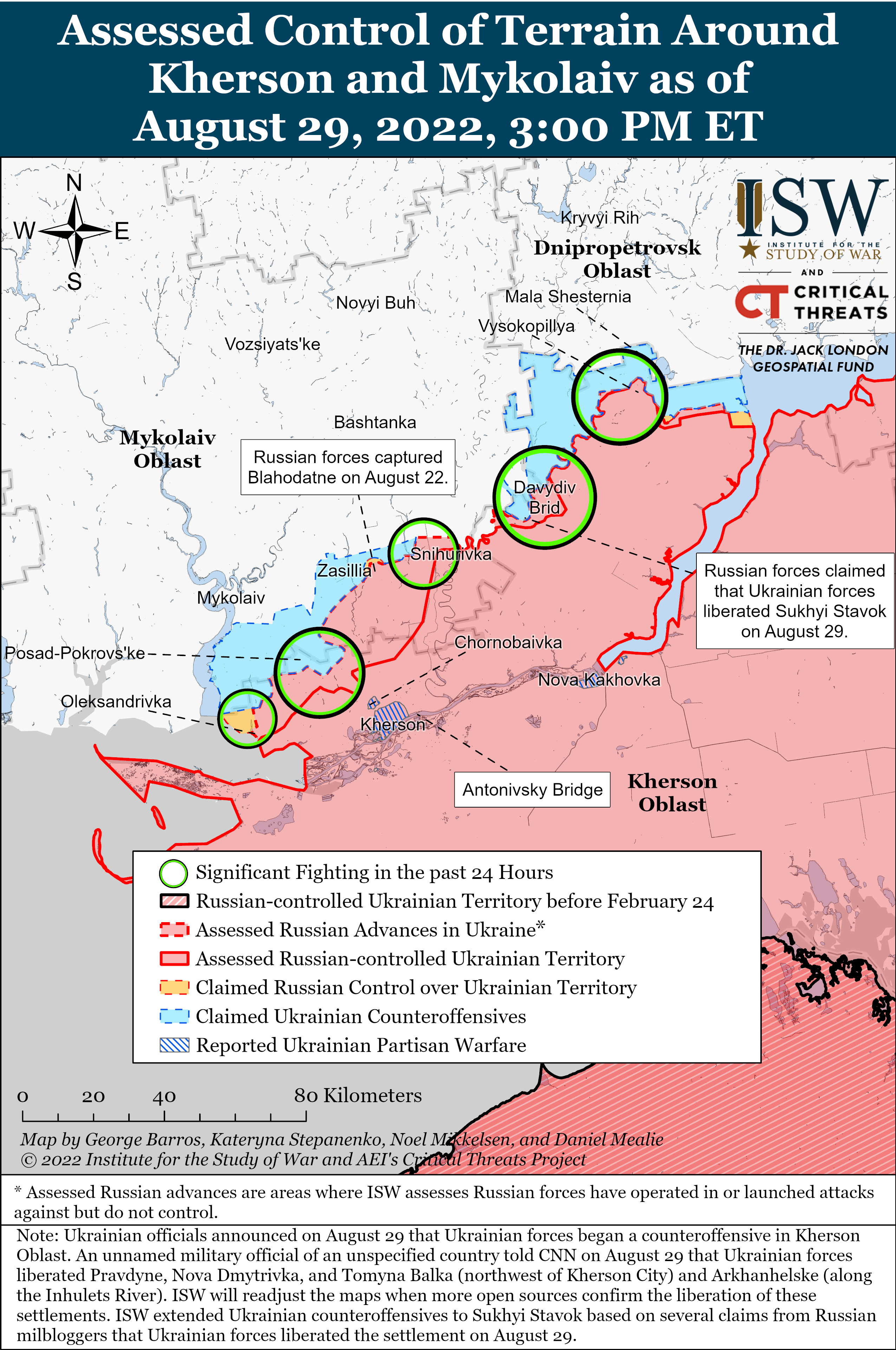

Operationally, Kherson is the media focal point, but the real objectives are to throw the Russians back over the Dnipro River, providing both an effective geographical barrier to any counter-counteroffensive, as well as legitimating the Ukrainian claim to river access extending to the Black Sea in any cease-fire in-place that might occur in the immediate future. Behind this effective defensive barrier, the Ukrainians have a perfect staging area for strikes against a number of targets currently out of reach by massed or precision fires: the entirety of the North Crimea Canal, the geographic bottleneck and post-2014 border at Armiansk, dozens of kilometers of the main east-west road from Melitopol, and much more. Crossing the river to continue retaking ground on the south bank is an order of magnitude more difficult unless the Russians truly collapse, and I do not expect the Ukrainians to be planning for it at this stage. An envelopment, thrusting south on multiple axes to the river, then attempting to encircle and collapse the remaining pocket of Russian resistance (preferably keeping them outside the city of Kherson, which could be costly to retake directly), seems most likely.

Strategically, there are some indications that a reverse on the battlefield now would be particularly bad timing for the Russians, who are showing more signs of structural weakness in their long-term ability to maintain their effort. Reports on shortages of PGMs, reductions in available forces for high-profile exercises with China, and limited Western success in dealing with the energy issue all point to a weakening of Russia's ability to leverage the strategic situation in their favor. This does not mean anything in the short term, but Russia will have to be working out how to address these issues now if it wants to arrest the decline. This probably means more cooperation with Iran and China, more efforts to distract or weaken the West with influence operations, cyberattacks, and support for anti-Western insurgencies and rogue states. The weaker Russia gets strategically, the fewer options it has; Western leaders should strongly and actively avoid pushing Russia too far into a corner, where Putin is likely to feel he must fight his way out by any means necessary if he wants to survive. If Russian weakness becomes more pervasive, expect to start hearing more Western voices pushing for a negotiated solution, no matter how unpopular this might be with the Ukrainians, who see near-term Russian weakness as perhaps their only opportunity to restore their territorial integrity. The biggest winner in any prolonged decline in Russian strategic leverage, however, will be China; Xi knows this, and certainly will help Putin continue for as long as he wishes, but only enough to keep fighting (and not enough to significantly endanger China's commercial relations with the West), not to win.